Carder

Professional

- Messages

- 2,616

- Reaction score

- 1,940

- Points

- 113

All-seeing eye

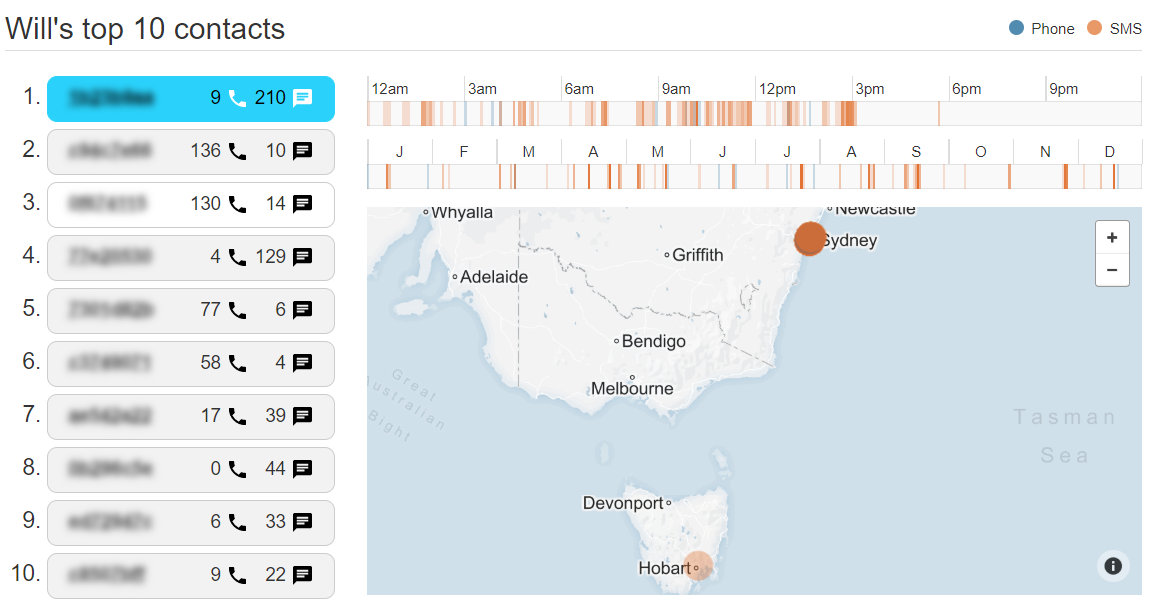

Often, the police will not even try to hack or intercept something, but will simply make a request to the cellular operator, and the latter will give back not only the call history, but also a lot of other interesting information. As an example: an article about an Australian journalist, which analyzes the information collected about the journalist by his mobile operator over the past two years (and only that).According to Australian laws, cellular operators are required to store certain information about network users, the Call detail record base, for two years . This includes information about the location of the device at each moment in time (by the way, a precedent was recently set in Sweden: this information alone is not enough to pass a sentence), a call log, including information about another subscriber, and data about Internet sessions. As for SMS, under the Australian privacy law, without prior authorization for wiretapping, the operator has the right (and is obliged) to save only metadata: the time of sending, the size of the message and the addressee. The content of the messages themselves (much less voice calls) is not saved.

This is how the information collected by the operator about the journalist looks like.

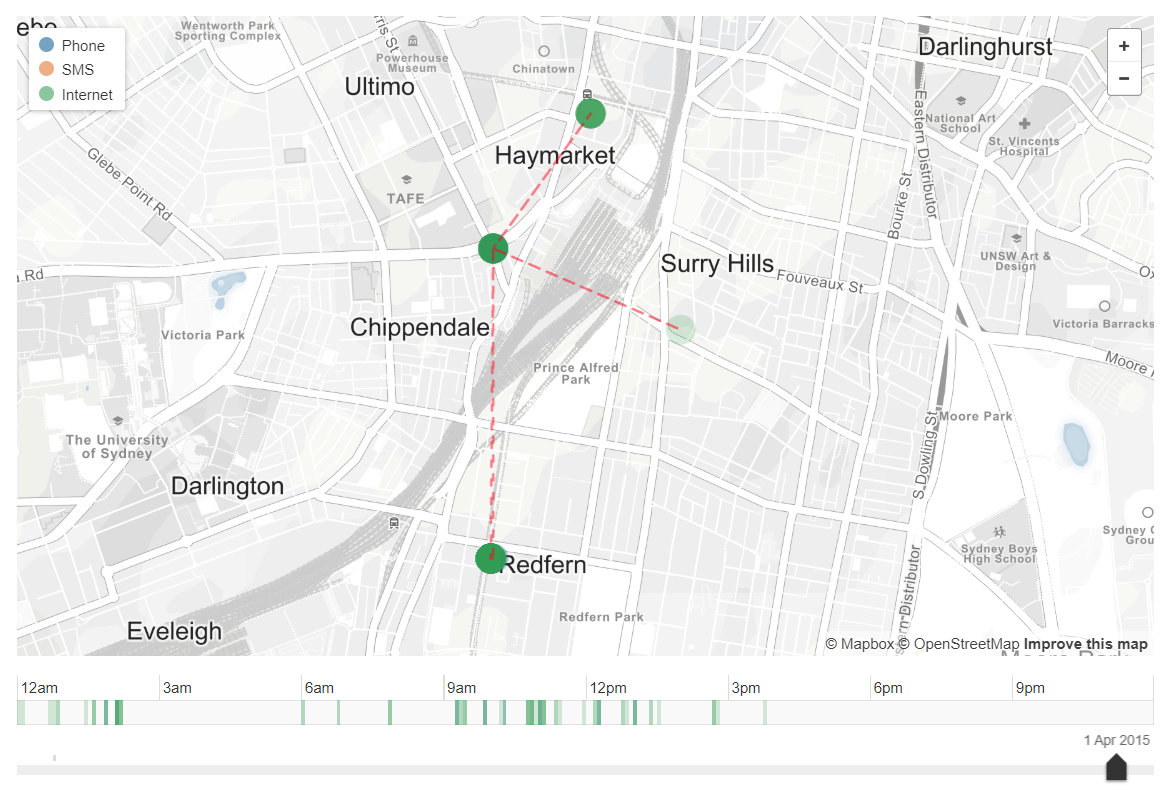

Places visited by the journalist.

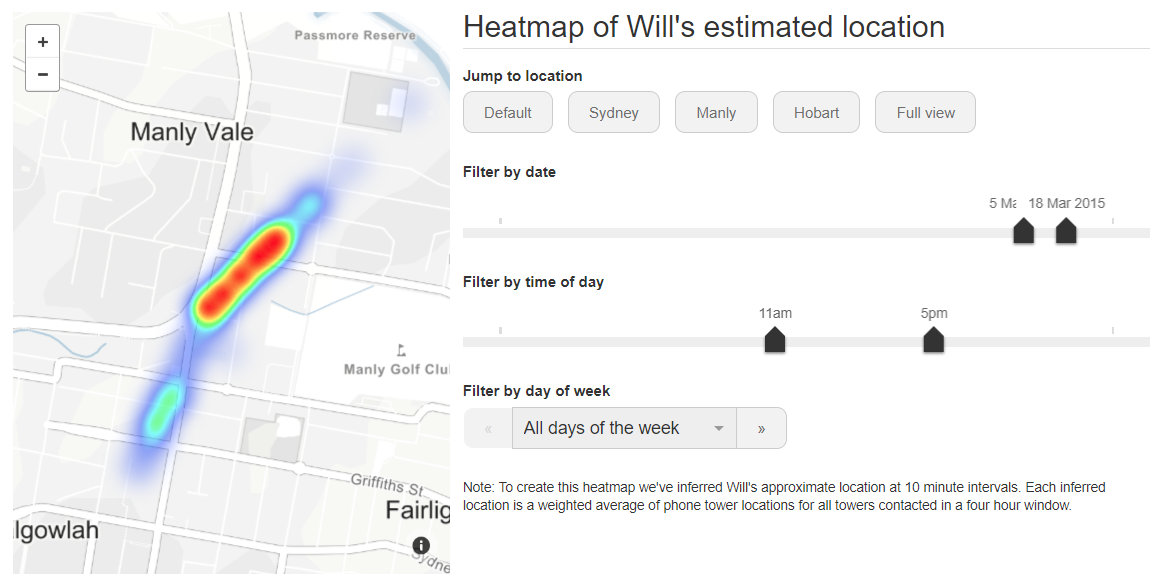

Places that he most often visited during a given time period.

The link are available online version of the data.

Metadata includes information about who the user called and wrote messages to, about the duration of calls and about which base stations the phone was connected to at what point in time (such information allows you to accurately determine the location of the device). In some countries (we will not point the finger, but this is the United States), operators not only give out information about the location of the police user, but also gladly trade in such data.

The most interesting thing is that mobile operators have access (and are issued to the police, as well as are sold to anyone who wants to) details about the use of the Internet, including website addresses and the amount of data transferred. This is a completely separate topic for discussion; the data is collected by tracking requests to the provider's DNS servers. Operators are also happy to trade with these data; The trough is so attractive that operators have even tried to block customers from using third-party DNS servers.

INFO

US mobile operators are also required to keep CDR records. In addition, in the United States, the intelligence services maintain a single MAINWAY database , in which records can be stored for much longer than is allowed by law by mobile operators themselves.By the way, devices issued (imposed) by stationary Internet providers (usually a combined cable or ADSL modem + router) often do not allow changing the DNS server on the router. If you want, change it on the computer, on each individual phone, smart TV and speaker, but the user will not be able to protect his privacy completely by simply setting the router settings.

In Russia, the so-called Yarovaya Law was adopted, which obliges mobile operators to store metadata for three years (their list almost completely coincides with the Australian version of the law). In addition, operators are required to store for at least 30 days (but not more than six months) text, voice, video and other messages of users. Accordingly, in Russia, any call must be recorded by the operator and provided to the police upon legal request.

Not only CDR

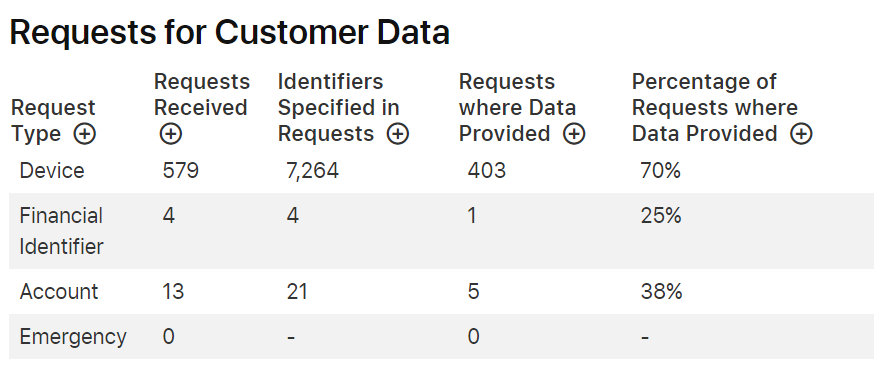

In the above study, journalist Will Oakenden used an iPhone. A properly executed request to Apple (in the company's terminology - Device Request, that is, such a request in which the police have nothing but the hardware device identifier - IMEI) will allow the police to receive the data that is collected about the Apple user, and this includes almost everything with rare exceptions. This is how, for example, the statistics of requests to Apple in Russia looks like.

For comparison, in the United States, in the same year, the police requested information on 19,318 devices (81% of requests were successful). Google offers an interactive graph, which can be viewed here.

And unless Apple provides the police with data such as user passwords, device usage statistics, SMS / iMessages, and Health data (the user's physical activity history, including the number of steps and heart rate in a given time frame, is the most useful thing to catch as criminals and unfaithful spouses), then Google will give everything, including passwords (to be completely technically correct, I will add that encryption of backups appeared in Android 9; accordingly, the police will not receive either the backups themselves, or the SMS and logs stored in them calls)

Disposable Phones

Criminals using their main phone for threatening calls, extortion and other criminal acts are now almost nonexistent; above we figured out in detail why. What remains for the criminal? Disposable SIM-cards (perhaps, we will not discuss now the ways in which criminals acquire such cards) and disposable (usually cheap push-button) devices, preferably completely devoid of Internet access.In order to get at least some information about a suspect, the police need at least one clue - IMEI is enough. But what can you tell from a device ID that has only been turned on for a few minutes? Having read conspiracy theories (an excellent example), novice criminals tenderly remove the battery from the phone, including the device, just to make a call.

Of course, none of them even think about what happens when the device turns on and off (both normally and emergency, with the battery removed). Moreover, few people think about whether the operational police officers know about such a template.

Confident in his safety, the criminal leaves the house (if he does not leave, it is highly likely that his location will be determined immediately or after the fact by analyzing the logs) and calls from a disposable phone. Where is his main phone? Let's consider the options.

Method 1

Let's start by looking at the most typical situation: a “suspicious” call is made from a one-time, “anonymous” phone, and the criminal took his own phone with him. There is nothing incredible in this; it is enough to read police reports to understand that this is how the majority acts.The police will ask the cellular operator for the CDR records for the specified period. Depending on the country and the laws in force in it, the operator returns either raw data or an anonymized list of devices (each hardware identifier is replaced with a hash function). In fact, the police receive a ready-made list of devices connected to the cell where the device from which the call was made was registered. It is assumed that among these devices will be present and the criminal's own phone.

Several thousand subscribers can be simultaneously connected to the same cell, so a single request will give little to the police. However, if the perpetrator calls the victim again - whether from the same cell or from a different (even better) cell - the police will receive additional samples. Further, the set of devices that were registered in the same cell at the time of the call from the "anonymous" device are crossed; as a rule, only a few dozen or even single identifiers remain in the second or third sample.

Of course, in practice, everything is somewhat more complicated. For example, not only the connection to a particular tower from which the call was made is taken into account, but also data from neighboring towers. The use of these data allows (and allowed, by the way, even fifteen years ago) to perform triangulation, determining the location of the device with an accuracy of several tens to several hundred meters. Agree, it's much more pleasant to work with such a sample.

However, in large cities with a high population density (anonymous calls are often made in crowded places) the circle of suspects, even as a result of the third sample, may turn out to be too wide. In such cases (not always, but in especially important cases) the analysis of "big data" comes into play. I was able to learn more about this two years ago from the opening speech at the police congress in Berlin. The analyst examines patterns of device behavior indicated by conditional identifiers. Talking on the phone, active traffic consumption, movement in space, registration time in the cell and a number of additional parameters allow excluding a significant part of the devices, thereby significantly reducing the number of suspects.

Conclusion: the easiest way to detect a criminal who has a personal device (personal smartphone) with him and who moves at the same time. Made an anonymous call from one cell - many devices outlined. I made a second call from another cell - and the list of devices following the same route was reduced by an order of magnitude.

By the way, I will debunk the popular cinematic template. To accurately determine the location of the phone, the time it is on the network does not play the slightest role: the location is determined instantly when the phone is registered on the network and is saved in the logs, from where it can be easily retrieved. If the device is moved, the location can be established even more accurately. At the same time, let's go through the conspiracy theorists: the switched off phone does not report its location, even if you do not remove the battery from it (well, the iPhone 11 can communicate thanks to the U1 chip, and even then not now, but sometime in the future, when Apple turns on this feature in firmware).

To summarize: the criminal turned on the device, made an anonymous call or sent an SMS, turned off the device, or removed the battery. The next day I turned it on again, called from another part of the city, turned it off. The list of devices that may belong to the criminal has been reduced to a few pieces. The third call made it possible to definitively identify the offender, you can leave. All this - without the use of any special tools, a simple analysis of logs for three inclusions.

Method 2

"Who goes to business with the phone on?" - you can logically ask. Indeed, a prudent criminal can turn off the main phone before making a call from an anonymous device. Very good: now the police only need to look at the list of devices that were turned off at the time of the anonymous call. In this case, one iteration is enough. If the offender also turns on his main phone after an anonymous call, then you can safely send a task force for him.Why is that? The fact is that when disconnected, the phone sends a signal to the cell, and this allows you to distinguish devices that have been disconnected from those that have left the cell. When enabled, a new record is created accordingly. Tracking such activities is a matter of a few clicks.

Method 3

"Who even takes their own phone with them?" Oddly enough, they take and carry, and not only phones. Take phones or leave your phone at home, but take a smartwatch; incidentally, this allowed the police to solve a lot of crimes. Most of the "telephone" criminals are far from professionals, and their knowledge of how cellular communication functions, what data is collected and how it is analyzed is in its infancy. The human factor allows the police to solve many crimes by simply comparing the facts.If the criminal really never takes a phone with him (practice shows that usually at least once, but everyone is wrong), then big data analysis can help to calculate it. Much here will depend on how much time the attacker is willing to spend and how much effort the attacker is willing to put into making an anonymous call, as well as how many such calls will be.

If there are many anonymous devices

And what if the criminal is cunning and uses not one, but several anonymous phones, getting rid of evidence every time after a call? This practice is often shown in films. After reading the previous sections, you probably already realized that all that a criminal gains from using several different devices is a few extra seconds of anonymity, those that precede the actual call. As calls from all anonymous devices will be added to the case, the police have additional leads: the source of the "anonymous" SIM-cards and, possibly, the place of purchase of disposable phones. The call was made from the same device or several different ones, will not affect the course of the investigation.Telephone terrorism: what if the call was really one?

What if there was really only one call? In order to inform about the mining of a school or airport, a second call is not needed: a telephone terrorist only needs to make one call, after which the “lit up” device can be thrown away or destroyed along with the SIM-card.Surprisingly, and such criminals are often caught using operational-search measures, worked out in the days of calls from street payphones. If a criminal has a permanent smartphone, then the circle of suspects can be sharply limited by conducting an analysis using the first of the methods described in the article. Thus, even in a city with a population of over one million, the circle of suspects narrows down to several hundred (rarely thousands) subscribers. If we are talking about "mining" the school, then many "suspicious" subscribers intersect with many of the school's students. It will be enough for the operative to just talk to those who remain.

The fact that such criminals, as a rule, have little idea of the possibilities and features of the work of operatives and try to protect themselves from invented, non-existent dangers, completely ignoring the obvious, helps in disclosing telephone terrorism. Two years ago, the office of our colleagues (coincidentally also the developers of software for the police) was evacuated by a call from an unknown person who reported an explosive device in the building. Less than a few hours later, the police had already detained the criminal. The culprit turned out to be a crazy grandmother who wanted to annoy the neighbors, but got the address wrong. Neither a push-button telephone specially bought by a vengeful old woman, nor an "anonymous" (or rather, registered to a non-existent name) SIM-card helped.

What about VoIP calls using a VPN?

If it occurred to you that a really anonymous call can be made through the VoIP service (preferably free, so as not to shine the means of payment), and even through a VPN service that does not store logs, congratulations, you think like a real bandit.Of course, there is always a chance to "puncture" by forgetting to control the connection to the VPN server or by accidentally entering with your own, not "anonymous" data for calls. To prevent this from happening, criminal groups go to serious expenses, ordering the manufacture of modified (at the software level) phones. The case of the arrest of the CEO of a company that produces such devices based on old BlackBerry phones, showed the scale of operations. Despite the fact that the police managed to shut down this criminal network (and gain control over the encrypted communications infrastructure used by the criminals), the police understand that this is only the first step. “Criminals inevitably migrate to other services, and we can imagine which ones. I will not point a finger, but sooner or later we will get to them ”(AFP Assistant Commissioner Gogan).

How the analysis works

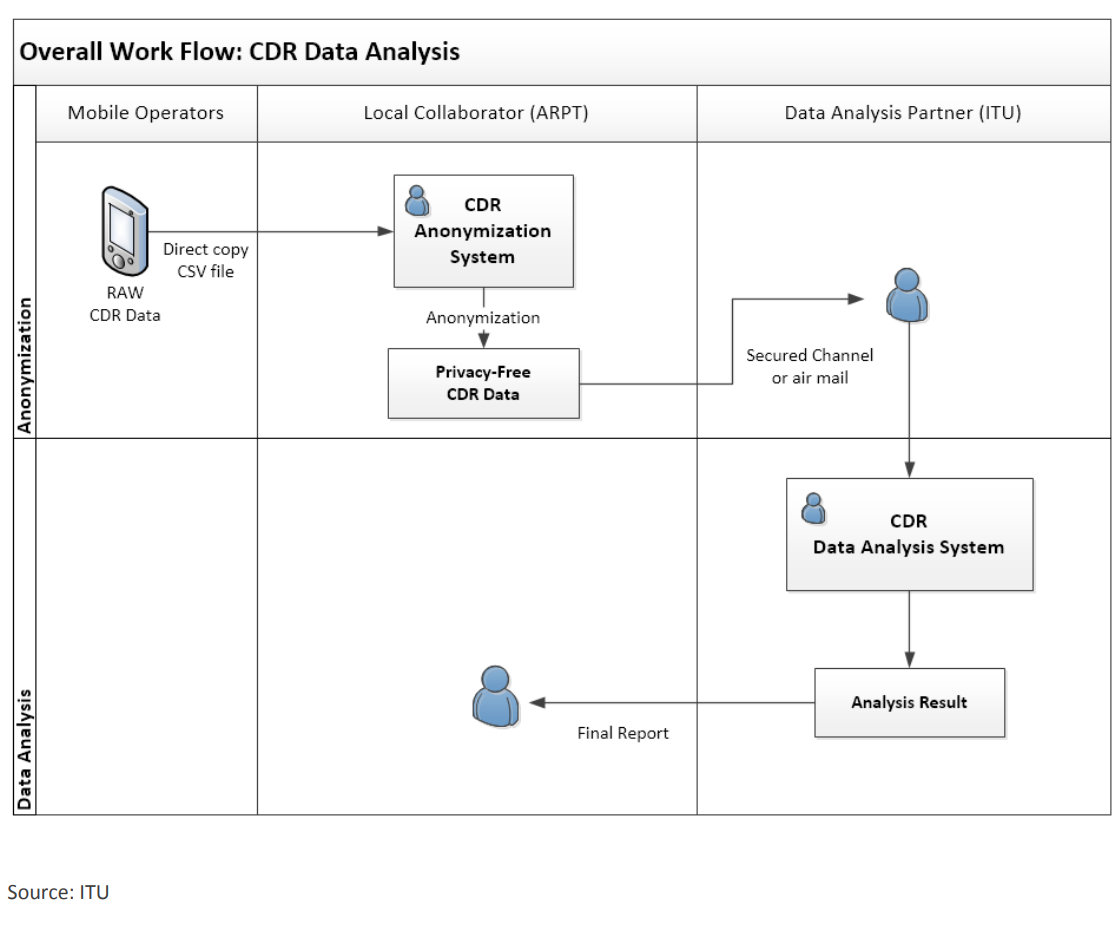

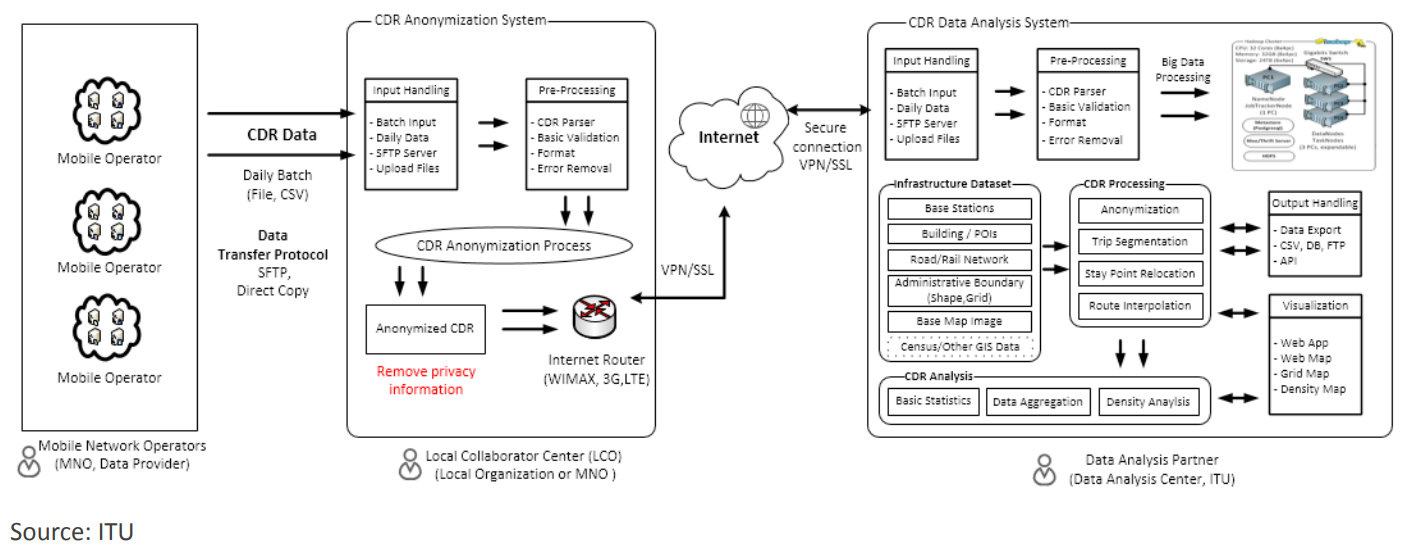

The report, published by the ITU (Republic of Guinea), describes in some detail both the methods and tools used by analysts. In general, the process can be depicted as follows.

And in a little more detail.

All the police need is actually "raw" CDR data and software that can be used to download and analyze it ("raw" data is not very useful for manual analysis, but filtered data can be displayed in text form or printed).

The popularity of this method of investigation is evidenced by the fact that CDR records are supported by almost every serious forensic package. Examples: Penlink, HAWK Analytics, GeoTime, CSAS, Oxygen Software's Russian Oxygen Forensic Suite, Advanced Cell Tracking and many others. However, we also had to communicate with police officers who successfully use a combination of Google Maps and Microsoft Excel in their work.

Without a doubt, the special services have special equipment in service that allows them to suppress cellular communications, replace a base station or fake GPS coordinates. Only the police do not use most of this technique - at least in the investigation of routine crimes of telephone terrorists and ransomware. Expensive, fussy, time consuming, and by and large not necessary, and sometimes ineffective. Analyzing CDR (Call Detail Record) logs is a much more efficient investment of time and effort.

A case that happened a few years ago in Great Britain is indicative. The police were monitoring one of the bosses of the drug cartel. Detention is not a problem, but there is no evidence, the case would have collapsed in court. According to the police, the criminal's phone (he used an iPhone) could contain vital evidence, but it was not possible to crack the lock code of a sufficiently fresh model at that time. As a result, an operation was developed; the criminal was under surveillance. As soon as he took the phone, unlocked it and started typing, the drug lord was detained, and the phone was literally snatched from his hands.

The interesting thing here is not the background, but such an insignificant detail: in order to take the criminal's iPhone to the laboratory in an unlocked state, a special policeman was appointed, whose whole work was reduced to periodically swiping his finger across the screen, preventing the device from falling asleep. (You don't need to think of the police as idiots: everyone knows that there is a setting that controls the time after which the phone screen turns off, and the phone itself is locked. But that on the phone it is easy, in a couple of clicks, you can install a configuration profile that prohibits disabling automatic blocking, not everyone already knows.) The phone was successfully taken to the laboratory, the data was extracted, the necessary evidence was obtained.

Somehow it's all ... unreliable!

If, after reading this article, you got the impression that it is somehow not entirely correct to base the verdict on data received from cellular operators, I hasten to agree. Moreover, the Danish Supreme Court agrees with you, which restricted the use of location data from CDR records by the prosecution. The ban did not appear out of the blue: out of 10,700 convictions based on these data (which is a lot for a quiet small country), 32 people have already been found innocent as a result of additional checks. According to the director of the Association of the Telecommunications Industry, "this infrastructure was created to provide communication services, and not to spy on citizens." "Attempting to interpret this data leads to errors," and "evidence that appears to be based on accurate technical measurements is not necessarily of high value in court."Most refresher courses for police officers are required to say that digital evidence cannot be completely trusted, regardless of the way it was obtained. They talk about cases where the location of a suspect was determined based on metadata from photos that were synced through the cloud, and not taken by the device itself.

An indicative case is when the answer to an incoming call was interpreted as "distraction while driving", which led to an emergency. In fact, the then push-button telephone was still peacefully in the driver's pocket, but because of the accidentally pressed button, the phone “answered” the call, which was registered by the operator. The defense was able to acquit the driver by interrogating the second subscriber, who showed that the conversation did not take place (by the way, what was there "in reality" is unknown, but the court sided with the accused).

I am sure this is not the only case. CDR data is an excellent tool in the hands of an operative, but not reliable as an evidence base.