Hacker

Professional

- Messages

- 1,041

- Reaction score

- 850

- Points

- 113

The content of the article

Wobbly DNS Clamp

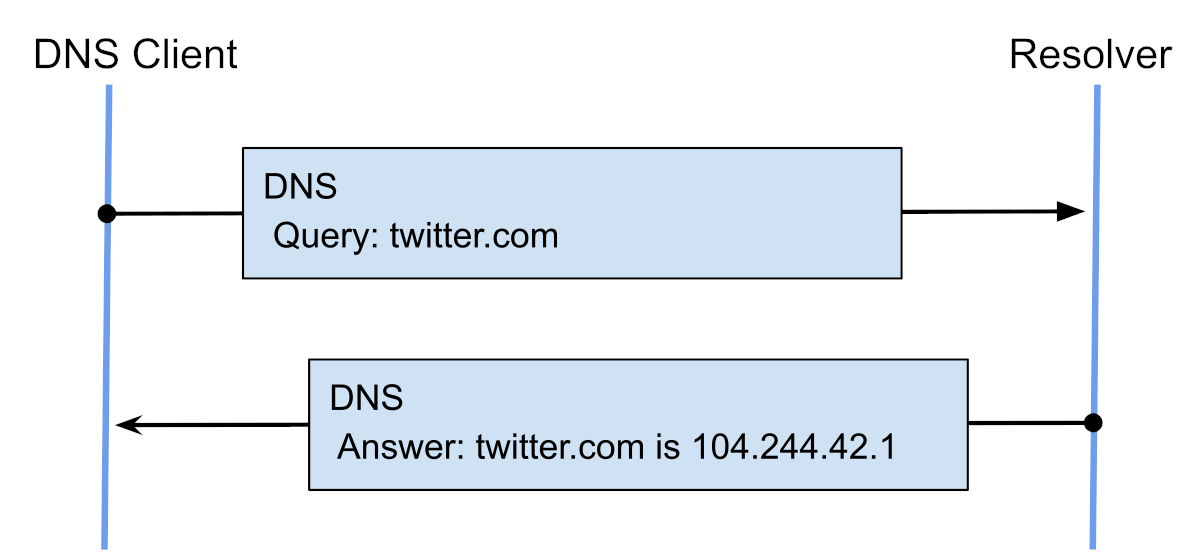

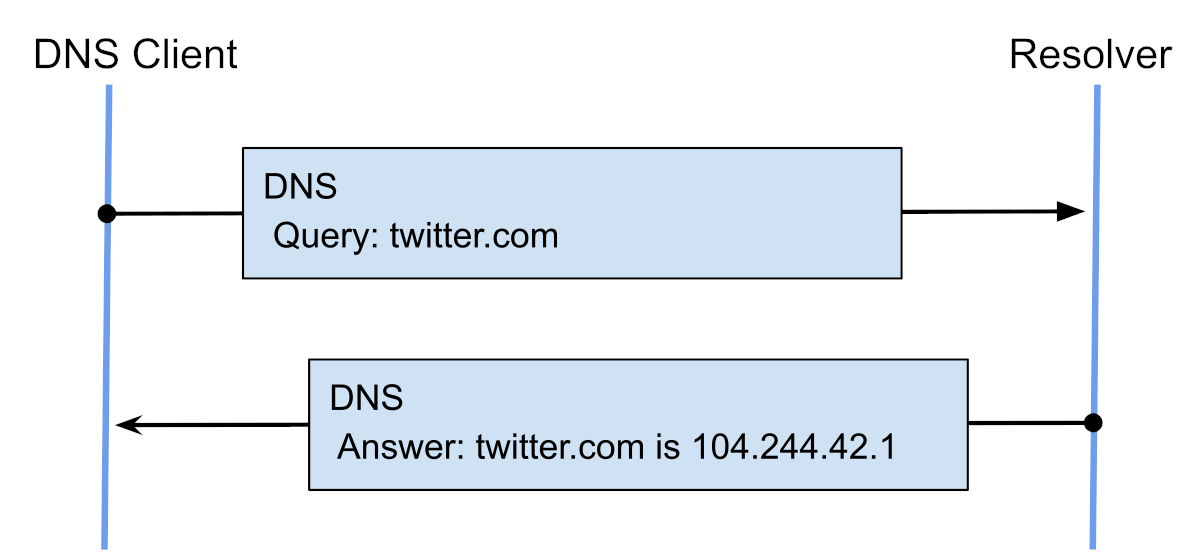

For order and consistency of presentation, we briefly recall the basic concepts. The Domain Name System (DNS) is one of the technologies at the very core of the modern Internet. It is used to correlate numeric IP addresses and more human-friendly domain names. It is built on the principle of hierarchical interaction between DNS servers.

An important point: this system was developed back in 1983 and therefore has some security issues. After all, the Internet then, as you know, was a network that connected American scientific and military institutions, and it was not planned to connect anyone to it.

In short, the root of the problem is that the underlying DNS system accepts and forwards any requests that go into it. As with many solutions that appeared in the early days of the Internet, there is no protection against malicious use. In those days, it was believed that the main thing was simplicity and scalability.

As a result, various methods of attacking DNS servers have emerged (for example, poisoning the DNS cache or hijacking DNS). The result of such attacks is the redirection of client browsers somewhere that users were not going to get.

To combat these ills, the Internet Engineering Council developed a set of DNSSEC extensions that added signature-authentication based on public key cryptography to DNS queries. But this set of extensions has been in development for a very long time. The problem became apparent in the early nineties, the direction of work on the problem was determined by 1993, the first version of DNSSEC was prepared by 1997, they tried to implement it, they began to make changes ...

In general, by 2005, a version suitable for large-scale use was created, and it began to be implemented, spreading the trust keychain across the Internet zones and DNS servers. Implementation took a long time too - for example, only by March 2011 the .com zone was signed.

But DNSSEC solves only part of the problem - it guarantees the authenticity and integrity of data, but not their privacy. In the struggle for this goal, encryption is a logical means. The question is how exactly to implement it.

Encryption options

Several development groups have proposed their own options for technological solutions. Among them are those that use original encryption methods, such as DNSCrypt or DNSCurve, which uses elliptic curve encryption. But the solutions that turned out to be more popular in the end rely on the widespread security protocol TLS. Such solutions are DoT (DNS over TLS) and DoH, the main focus of this article.

DoT, as its name suggests, uses the TLS protocol itself for encrypted transmission of DNS queries. This entails a change in the main ports and protocols - instead of UDP on port 53, TCP is used on port 853.

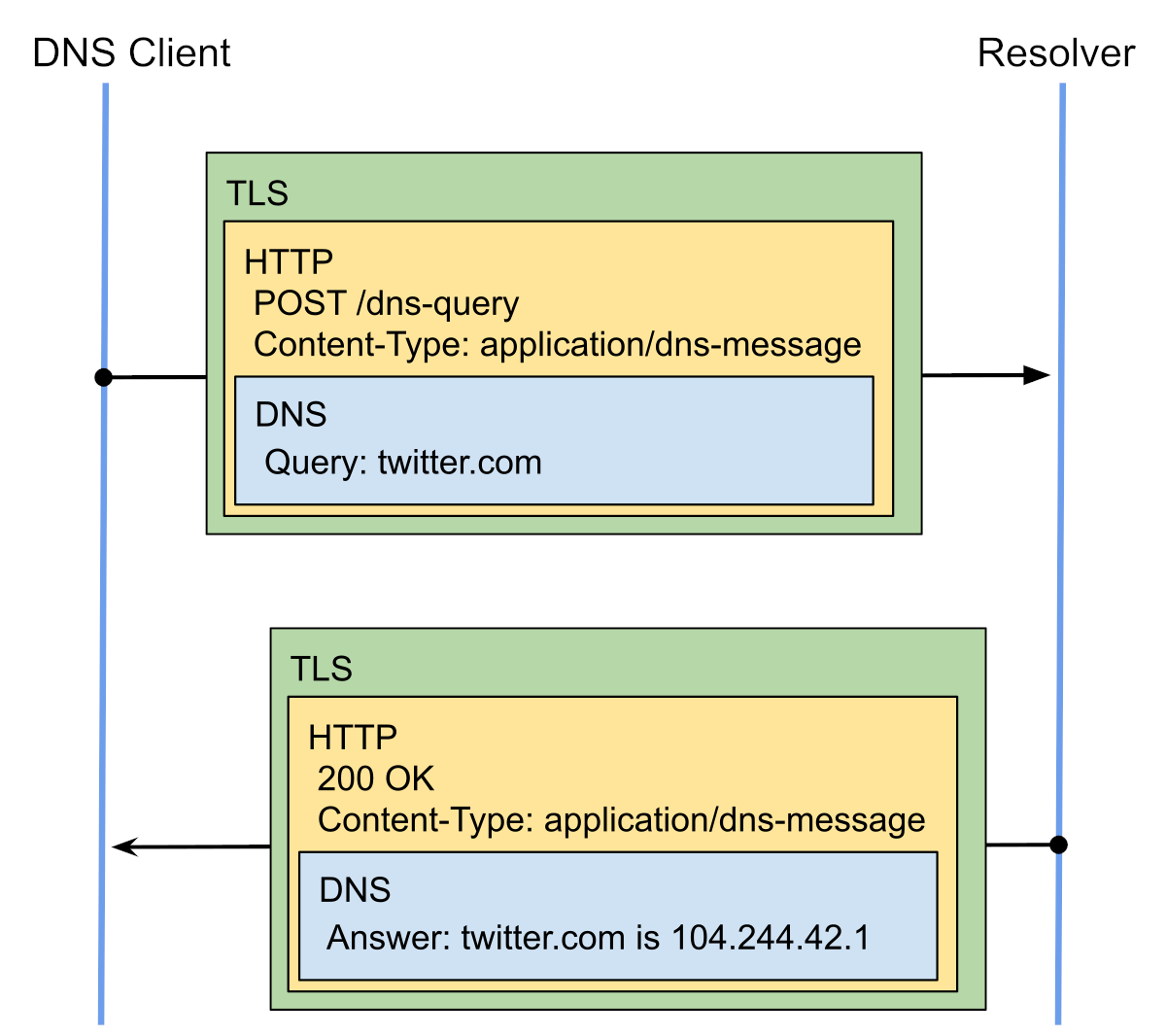

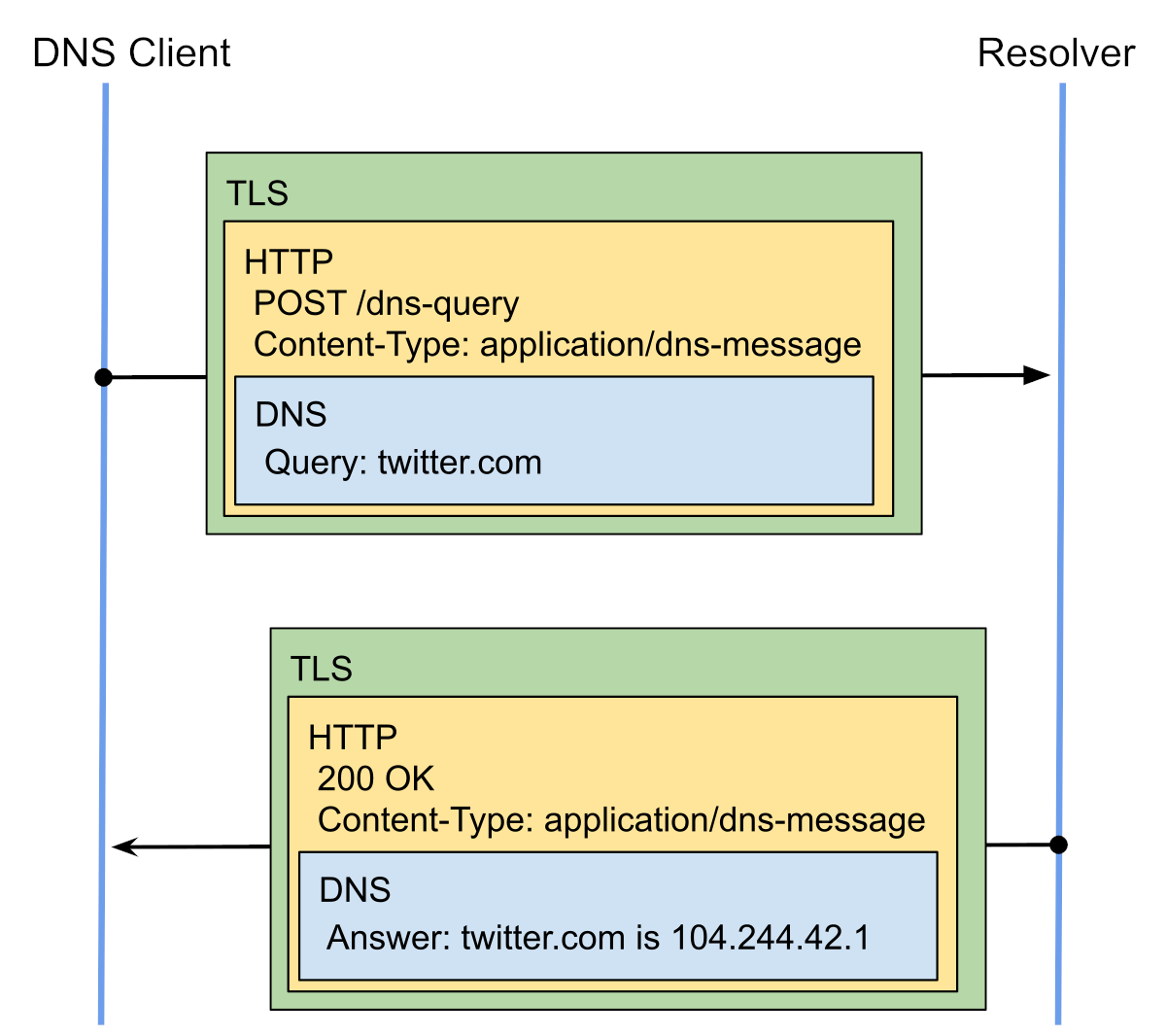

DoH works differently and uses TLS differently. In DoH, TLS encryption is applied at the HTTPS protocol level, using HTTPS requests and accessing the HTTP ports of the DNS server.

Sounds complicated? Jan Schauman talks about this very accurately and intelligibly:

DoH odim to the point

Here it is reasonable to ask the question: what could be the problem here? The more security the better, isn't it?

The answer to this question lies in the nuances of the chosen solutions, their strengths and weaknesses. Namely, in how the new technology interacts with different participants in the DNS system, which of them are considered by its developers to be conditionally trustworthy, and who are sources of threat. And now we're not even talking about malevolent hackers with openly criminal goals.

The point is that there are intermediaries between the user device and the final site. The network administrator, firewall, Internet provider - all of them can interact with the DNS system in their own interests, setting their DNS name resolvers settings for which requests to track, block, modify. This is how you can embed ads, cut off malicious content, and prevent access to certain resources ...

DoT, working over TLS with its trust certificate system, also needs a DNS resolver that it can trust. There is a flexible ability to customize the list of trusted resolvers, the ability to centrally change settings in a previously trusted (for example, corporate) environment, as well as the ability to switch back to the basic DNS if problems arise with the new version.

Since a new, dedicated port is used for DoT, it is possible to notice the transmitted traffic and monitor its volumes, encryption does not interfere with this in any way. If you wish, you can even block it altogether.

In general, DoT needs to be configured correctly, but it contains some functions that are extremely useful for system administrators and network engineers. Therefore, many of the professionals praise DoT for this.

With DoH, the story is different. This technology was developed with a view to custom applications, namely browsers. This is a key detail in this whole story. It means this. When using DoH, all traffic that is not related to browsers goes through the basic DNS, but browser traffic bypasses any DNS settings - at the operating system, local network, provider level - and, bypassing intermediate stages, goes directly to the supporting DoH via HTTPS DNS resolver.

And there are a number of serious questions to this scheme.

Insidious villains and conspiracy theories

So we got to the story of who nominated Mozilla for "Internet villain of the year." This is the British Association of Internet Service Providers and the British Internet Surveillance Foundation. These organizations are responsible for blocking inappropriate content for UK internet users. They mainly fight against child pornography, but they are also interested in piracy, extremism and any other crime. For another time, they tried to ban BDSM pornography from British Internet users, but failed.

So, these organizations believe that the implementation of DoH will significantly narrow their ability to control access to content. Their concerns are shared not only by ISPs in other countries, but also by cybersecurity professionals who point out that firewalls and DNS monitoring systems will face the same challenges. And the protection of corporate networks will suffer from this, and employees will have new opportunities to download the virus from a phishing link. Moreover, there are already examples of how attackers abuse the capabilities of DoH.

In America, Google and Mozilla have entered a legal war with providers over DoH. First, providers turned to the US Congress with a written request to pay attention to the possible consequences of DoH implementation. Google managers were quick to reassure everyone that the dangers were exaggerated. But representatives of Mozilla themselves asked Congress to study the practice of collecting user data by providers, openly hinting that providers defend their specific interests.

But with the business interests of providers, everything is clear. And what are the interests of the supporters of the early implementation of DoH? Why are Google and Mozilla employees in every possible way that this is all just an experiment, and that if UK users need to be protected from pornography, they will not be included in the experiment, and that they just want to give users (including residents of countries with authoritarian internet controls) more privacy and security?

Some experts believe that it is a matter of DNS resolvers with DoH support. Both Google and Mozilla claim that their browsers will use a whole list of such resolvers, but in practice - Google has its own DNS server, and Mozilla is developing its solution in close collaboration with Cloudflare. It also provides its own DNS.

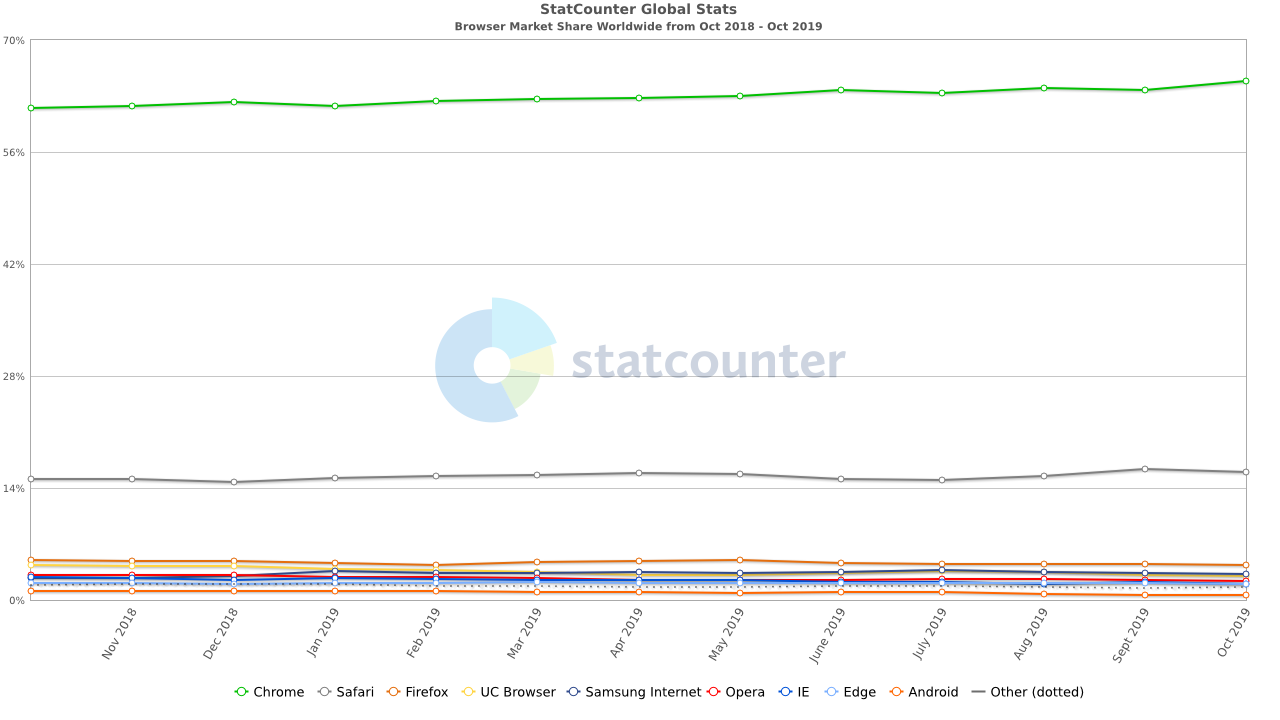

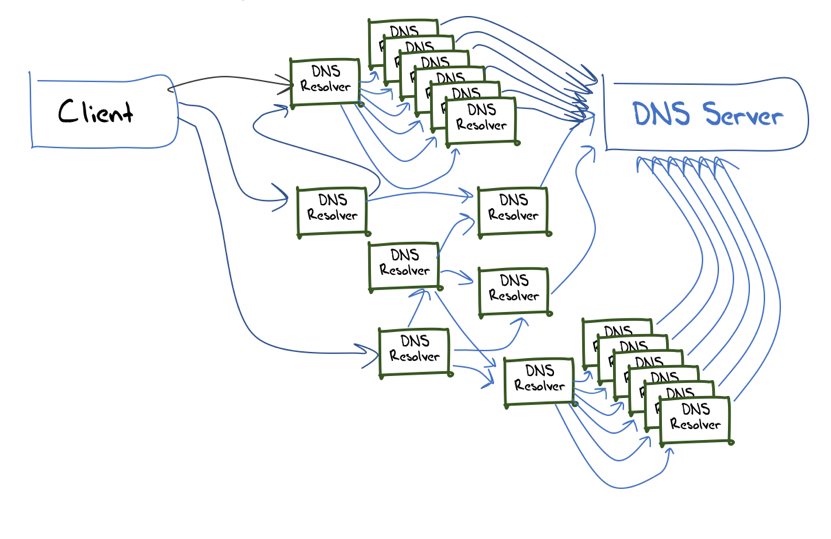

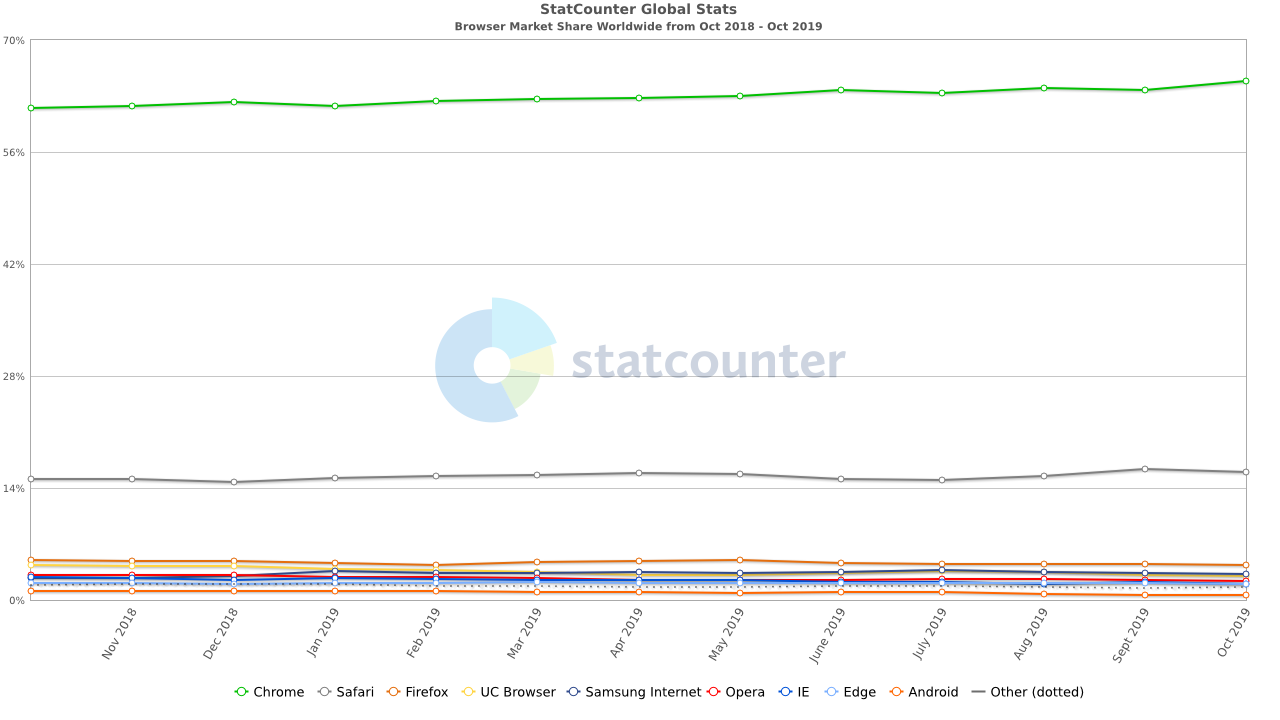

If, in addition to this, we recall that Chrome is now the most popular browser, then a not very pleasant picture emerges. In a distributed and decentralized DNS system, a huge segment, controlled by Google, and a smaller segment, owned by Cloudflare, will appear overnight. Nothing personal, dear providers, just business. The data was yours, but it is ours!

Mozilla states in its DoH Implementation FAQ that Cloudflare 's DNS resolver was not chosen because Cloudflare pays money for it. Mozilla and Cloudflare allegedly have no intention of monetizing the data passing through their servers, and are only interested in fighting for the privacy and security of Internet use.

Well, by corporate standards, Cloudflare is at least a bit like a sincere ally in this struggle - the company has repeatedly declared its commitment to the values of Internet freedom, network neutrality and free speech, and in its case such statements work on its image as an important player in the rapidly growing and the emerging market for digital privacy and security. But with Google, the case looks much more suspicious.

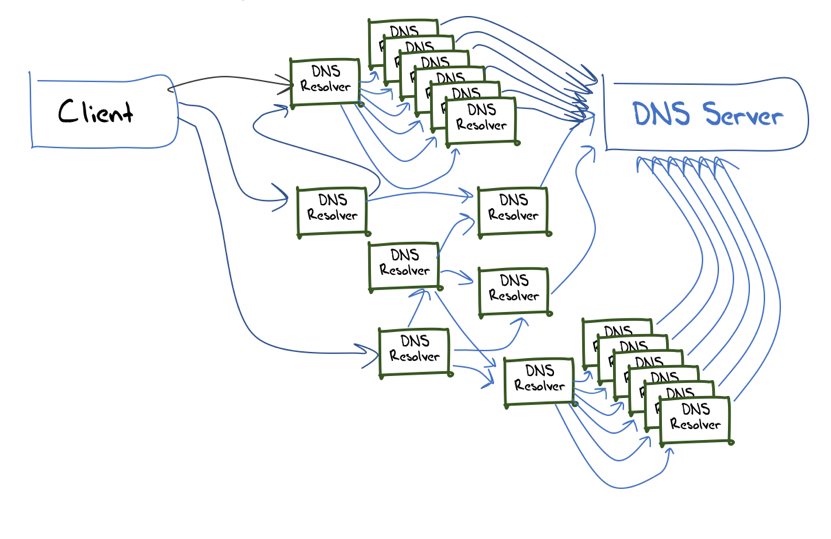

Google is rapidly moving towards monopolizing key services for the Internet, and some are already monopolized. And besides the economic and political aspects, there are also purely technical ones. The lack of centralization is deliberately incorporated into the Internet protocols - after all, the modern Internet grew out of an American military development, one of the goals of which was to maintain communication between its participants after atomic strikes. If some catastrophe physically destroys some of the data centers, servers or communication lines, the Internet must survive it.

But if several companies begin to exclusively provide important functions, then what will happen, for example, in the event of bankruptcy of one of them? These are, of course, all purely philosophical questions, but it is worth considering them. For example, the staff of the Asia Pacific Network Information Center (APNIC) believe that DoH implementation is a reason for serious research into the degree of centralization of the DNS system, and intend to closely monitor the process.

Conclusions

Let's summarize. And let's start with what can be said with complete confidence.

DoH technology will make life difficult for anyone who wants or has to monitor users' DNS traffic. These include providers, system administrators, developers and operators of firewalls and content filters, and government agencies that monitor the Internet.

How much will DoH make life difficult for them? No one can say for sure - it all depends on the pace of implementation and the elaboration of technological solutions.

Does the Internet need this technology? Difficult question. Experts agree that it is necessary to improve DNS security, but do not agree on exactly how - and many lament that the development of new solutions is being carried out unnecessarily hastily, is implemented with difficulty and, as a result, overcomplicates the technical device to such an extent that it becomes impossible to understand it. even to professionals.

Do you personally need DoH? As in many other cases, the question is rather which threat seems to be of higher priority to you. If these are providers doing something that you don't like, or content filters that you did not ask for (for example, government ones), then you may need another tool. If you are more worried about cybercriminals, or if you need to monitor so that some users do not go where they should not, it is worthwhile to carefully study how this technology will interact with your tasks.

"Why do I need all this nonsense at all, I have a good proxy and Tor as a fallback?" - you ask. If so, then you really don't need all of this. But it is not necessary - it does not mean uninteresting. Fortunately or unfortunately, on the Internet, our company is made up of billions of ordinary non-professional users, corporate network dwellers, silent and inconspicuous devices of network infrastructure and fashionable representatives of the "Internet of things". And everything described in the article can seriously affect them. But how exactly and with what consequences - no one knows yet.

And finally, Mozilla says that in some cases, using DoH significantly speeds up the processing of DNS queries. If they turn out to be right, they will go from “Internet villain of the year” to “Internet superheroes”. And, as they say in the stories of heroes and villains, to be continued.

- Wobbly DNS Clamp

- Encryption options

- DoH odim to the point

- Insidious villains and conspiracy theories

- conclusions

Wobbly DNS Clamp

For order and consistency of presentation, we briefly recall the basic concepts. The Domain Name System (DNS) is one of the technologies at the very core of the modern Internet. It is used to correlate numeric IP addresses and more human-friendly domain names. It is built on the principle of hierarchical interaction between DNS servers.

An important point: this system was developed back in 1983 and therefore has some security issues. After all, the Internet then, as you know, was a network that connected American scientific and military institutions, and it was not planned to connect anyone to it.

In short, the root of the problem is that the underlying DNS system accepts and forwards any requests that go into it. As with many solutions that appeared in the early days of the Internet, there is no protection against malicious use. In those days, it was believed that the main thing was simplicity and scalability.

As a result, various methods of attacking DNS servers have emerged (for example, poisoning the DNS cache or hijacking DNS). The result of such attacks is the redirection of client browsers somewhere that users were not going to get.

To combat these ills, the Internet Engineering Council developed a set of DNSSEC extensions that added signature-authentication based on public key cryptography to DNS queries. But this set of extensions has been in development for a very long time. The problem became apparent in the early nineties, the direction of work on the problem was determined by 1993, the first version of DNSSEC was prepared by 1997, they tried to implement it, they began to make changes ...

In general, by 2005, a version suitable for large-scale use was created, and it began to be implemented, spreading the trust keychain across the Internet zones and DNS servers. Implementation took a long time too - for example, only by March 2011 the .com zone was signed.

But DNSSEC solves only part of the problem - it guarantees the authenticity and integrity of data, but not their privacy. In the struggle for this goal, encryption is a logical means. The question is how exactly to implement it.

Encryption options

Several development groups have proposed their own options for technological solutions. Among them are those that use original encryption methods, such as DNSCrypt or DNSCurve, which uses elliptic curve encryption. But the solutions that turned out to be more popular in the end rely on the widespread security protocol TLS. Such solutions are DoT (DNS over TLS) and DoH, the main focus of this article.

DoT, as its name suggests, uses the TLS protocol itself for encrypted transmission of DNS queries. This entails a change in the main ports and protocols - instead of UDP on port 53, TCP is used on port 853.

DoH works differently and uses TLS differently. In DoH, TLS encryption is applied at the HTTPS protocol level, using HTTPS requests and accessing the HTTP ports of the DNS server.

Sounds complicated? Jan Schauman talks about this very accurately and intelligibly:

Since HTTPS uses TLS, it could be argued and argued that, technically, DoH is also DNS over TLS. But that would be wrong. DoT sends basic DNS queries over a TLS connection on a separate dedicated port. DoH uses the HTTP application layer protocol to send requests to the server's HTTPS port using and including all the elements of normal HTTP messages.

DoH odim to the point

Here it is reasonable to ask the question: what could be the problem here? The more security the better, isn't it?

The answer to this question lies in the nuances of the chosen solutions, their strengths and weaknesses. Namely, in how the new technology interacts with different participants in the DNS system, which of them are considered by its developers to be conditionally trustworthy, and who are sources of threat. And now we're not even talking about malevolent hackers with openly criminal goals.

The point is that there are intermediaries between the user device and the final site. The network administrator, firewall, Internet provider - all of them can interact with the DNS system in their own interests, setting their DNS name resolvers settings for which requests to track, block, modify. This is how you can embed ads, cut off malicious content, and prevent access to certain resources ...

DoT, working over TLS with its trust certificate system, also needs a DNS resolver that it can trust. There is a flexible ability to customize the list of trusted resolvers, the ability to centrally change settings in a previously trusted (for example, corporate) environment, as well as the ability to switch back to the basic DNS if problems arise with the new version.

Since a new, dedicated port is used for DoT, it is possible to notice the transmitted traffic and monitor its volumes, encryption does not interfere with this in any way. If you wish, you can even block it altogether.

In general, DoT needs to be configured correctly, but it contains some functions that are extremely useful for system administrators and network engineers. Therefore, many of the professionals praise DoT for this.

With DoH, the story is different. This technology was developed with a view to custom applications, namely browsers. This is a key detail in this whole story. It means this. When using DoH, all traffic that is not related to browsers goes through the basic DNS, but browser traffic bypasses any DNS settings - at the operating system, local network, provider level - and, bypassing intermediate stages, goes directly to the supporting DoH via HTTPS DNS resolver.

And there are a number of serious questions to this scheme.

Insidious villains and conspiracy theories

So we got to the story of who nominated Mozilla for "Internet villain of the year." This is the British Association of Internet Service Providers and the British Internet Surveillance Foundation. These organizations are responsible for blocking inappropriate content for UK internet users. They mainly fight against child pornography, but they are also interested in piracy, extremism and any other crime. For another time, they tried to ban BDSM pornography from British Internet users, but failed.

So, these organizations believe that the implementation of DoH will significantly narrow their ability to control access to content. Their concerns are shared not only by ISPs in other countries, but also by cybersecurity professionals who point out that firewalls and DNS monitoring systems will face the same challenges. And the protection of corporate networks will suffer from this, and employees will have new opportunities to download the virus from a phishing link. Moreover, there are already examples of how attackers abuse the capabilities of DoH.

In America, Google and Mozilla have entered a legal war with providers over DoH. First, providers turned to the US Congress with a written request to pay attention to the possible consequences of DoH implementation. Google managers were quick to reassure everyone that the dangers were exaggerated. But representatives of Mozilla themselves asked Congress to study the practice of collecting user data by providers, openly hinting that providers defend their specific interests.

But with the business interests of providers, everything is clear. And what are the interests of the supporters of the early implementation of DoH? Why are Google and Mozilla employees in every possible way that this is all just an experiment, and that if UK users need to be protected from pornography, they will not be included in the experiment, and that they just want to give users (including residents of countries with authoritarian internet controls) more privacy and security?

Some experts believe that it is a matter of DNS resolvers with DoH support. Both Google and Mozilla claim that their browsers will use a whole list of such resolvers, but in practice - Google has its own DNS server, and Mozilla is developing its solution in close collaboration with Cloudflare. It also provides its own DNS.

If, in addition to this, we recall that Chrome is now the most popular browser, then a not very pleasant picture emerges. In a distributed and decentralized DNS system, a huge segment, controlled by Google, and a smaller segment, owned by Cloudflare, will appear overnight. Nothing personal, dear providers, just business. The data was yours, but it is ours!

Mozilla states in its DoH Implementation FAQ that Cloudflare 's DNS resolver was not chosen because Cloudflare pays money for it. Mozilla and Cloudflare allegedly have no intention of monetizing the data passing through their servers, and are only interested in fighting for the privacy and security of Internet use.

Well, by corporate standards, Cloudflare is at least a bit like a sincere ally in this struggle - the company has repeatedly declared its commitment to the values of Internet freedom, network neutrality and free speech, and in its case such statements work on its image as an important player in the rapidly growing and the emerging market for digital privacy and security. But with Google, the case looks much more suspicious.

Google is rapidly moving towards monopolizing key services for the Internet, and some are already monopolized. And besides the economic and political aspects, there are also purely technical ones. The lack of centralization is deliberately incorporated into the Internet protocols - after all, the modern Internet grew out of an American military development, one of the goals of which was to maintain communication between its participants after atomic strikes. If some catastrophe physically destroys some of the data centers, servers or communication lines, the Internet must survive it.

But if several companies begin to exclusively provide important functions, then what will happen, for example, in the event of bankruptcy of one of them? These are, of course, all purely philosophical questions, but it is worth considering them. For example, the staff of the Asia Pacific Network Information Center (APNIC) believe that DoH implementation is a reason for serious research into the degree of centralization of the DNS system, and intend to closely monitor the process.

Conclusions

Let's summarize. And let's start with what can be said with complete confidence.

DoH technology will make life difficult for anyone who wants or has to monitor users' DNS traffic. These include providers, system administrators, developers and operators of firewalls and content filters, and government agencies that monitor the Internet.

How much will DoH make life difficult for them? No one can say for sure - it all depends on the pace of implementation and the elaboration of technological solutions.

Does the Internet need this technology? Difficult question. Experts agree that it is necessary to improve DNS security, but do not agree on exactly how - and many lament that the development of new solutions is being carried out unnecessarily hastily, is implemented with difficulty and, as a result, overcomplicates the technical device to such an extent that it becomes impossible to understand it. even to professionals.

Do you personally need DoH? As in many other cases, the question is rather which threat seems to be of higher priority to you. If these are providers doing something that you don't like, or content filters that you did not ask for (for example, government ones), then you may need another tool. If you are more worried about cybercriminals, or if you need to monitor so that some users do not go where they should not, it is worthwhile to carefully study how this technology will interact with your tasks.

"Why do I need all this nonsense at all, I have a good proxy and Tor as a fallback?" - you ask. If so, then you really don't need all of this. But it is not necessary - it does not mean uninteresting. Fortunately or unfortunately, on the Internet, our company is made up of billions of ordinary non-professional users, corporate network dwellers, silent and inconspicuous devices of network infrastructure and fashionable representatives of the "Internet of things". And everything described in the article can seriously affect them. But how exactly and with what consequences - no one knows yet.

And finally, Mozilla says that in some cases, using DoH significantly speeds up the processing of DNS queries. If they turn out to be right, they will go from “Internet villain of the year” to “Internet superheroes”. And, as they say in the stories of heroes and villains, to be continued.