Tomcat

Professional

- Messages

- 2,695

- Reaction score

- 1,060

- Points

- 113

In a post about the Internet of Things, I, almost with a saber drawn, included ATMs as such - according to the criteria of autonomous operation and the presence of a constant connection to the Internet. In general, everything is so, but if we move from words to action - that is, to the real specifics of protecting ATMs from hacking, then many inconvenient details immediately arise. A modern ATM is a full-fledged computer, tailored to perform one specific task, but capable of running any code, including malicious ones. The ATM is hung and comes into contact with many sensors and specialized devices through which the ATM can be hacked. Or you don’t have to hack, by intercepting control of a cash dispensing device or a keyboard for entering a PIN code.

There are many scenarios when something can go wrong with an ATM, and most are based not on a theoretical analysis of potential vulnerabilities, but on the practice of analyzing real attacks. The banking industry as a whole is much more secure than other industries, but cybercriminals also pay more attention to it: real money is at stake. Nevertheless, it would be nice to somehow systematize the weak points of the banking infrastructure, which is what Laboratory specialists Olga Kochetova and Alexey Osipov recently did.

As with the history of the investigation into the Lurk campaign, this text is a free retelling of the primary sources. I send them for details: this is a review article on Securelist in Russian, a study “Future scenarios of attacks on communication systems interacting with ATMs” in English, a brief summary from there - only a description of attacks and countermeasures, as well as earlier publications: a description of the malware Skimer and targeted attacks on Tyupkin ATMs .

Attacks on ATMs are not an entirely new topic. The first version of the Skimer malware appeared in 2008-2009. The attack is aimed directly at ATMs: in one of the current versions (Skimer exists and is still being developed today), after an ATM is infected, it can be controlled by inserting a prepared card with a “key” on a magnetic stripe into the ATM.

His brilliance!

True to its name, Skimer can enable the collection of data from cards inserted into an ATM, but it can also be used to directly steal cash - the corresponding command is provided in the control menu. Skimer is embedded in the legitimate SpiService.exe process, resulting in full access to XFS, a universal client-server architecture for financial applications on Windows systems.

Unlike Skimer, the Tyupkin attack, studied in the Lab in 2014, does not use prepared cards. Instead, the malicious code is activated at a certain time of the day, and even at this time, it is possible to intercept control of the ATM only after entering a dynamic authorization code. The consequences of a successful attack, however, are approximately the same:

Actually, the most interesting thing in these two examples is the infection process, which sometimes has to be reconstructed from CCTV camera recordings. In the case of Tyupkin, the malware was installed from a CD (!), meaning there was physical access to the insides of the ATM. This is an obvious attack vector with equally obvious disadvantages. But he is not the only one.

In the Carbanak campaign, the details of which were revealed by Laboratory experts in February last year, ATMs are used as a last resort, silently giving away the cash upon command from the center, without any on-site manipulation. The infrastructure of the victims was compromised, thanks to which the main damage was caused, as they say, by bank transfer. When losses are measured in hundreds of millions of dollars, cash ceases to play a significant role.

The trend continued to develop this year: in February, we reported on three new attacks, two of which were aimed at non-cash theft of funds. Only one campaign (Metel) involved withdrawing funds through ATMs, but no one hacked the devices themselves. Technically, the transaction (withdrawal of money from the account) was legitimate, but after it the card balance rolled back to its previous value. The modern version of the irredeemable nickel was operated, as in the case of other attacks, at night, preferably on weekends.

Cybercriminals will attack the root infrastructure of financial institutions as long as they have the opportunity, that is, while it is vulnerable. As the story of the robbery through the SWIFT interbank transfer system shows , even critical elements of the financial infrastructure are not always properly protected (isn’t it true that ATM protection is sometimes better?). I would like to believe that this will not last long. Considering that cybercrime about ATMs is never forgotten, they are the ones who claim the dubious privilege of a long-term headache for the financial industry.

In their analysis of future vectors of attacks on ATMs, our experts are not limited to direct cash theft. To this clear goal, let’s add the theft of customer data for the subsequent withdrawal of funds in larger volumes with less chance of being caught on a surveillance camera. But that's not all. If you look closely, you won’t be able to find a place in the entire IT “connection” of the ATM network that cannot be attacked.

An interesting example is biometric customer identification - a relatively new technology that allows you to either replace or supplement standard means of authorization - using a PIN code, using NFC, and so on. The theft of biometric data is theoretically possible through appropriately modified skimmers (if biometrics once again fails the previous mistakes with card readers), through a Man-in-the-middle attack (when an ATM starts sending data to someone else’s processing server), or through an attack on the infrastructure of a financial organization.

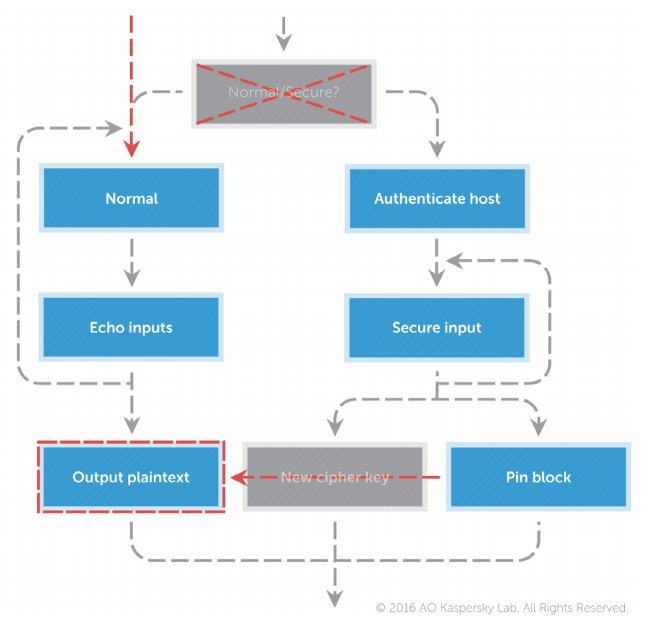

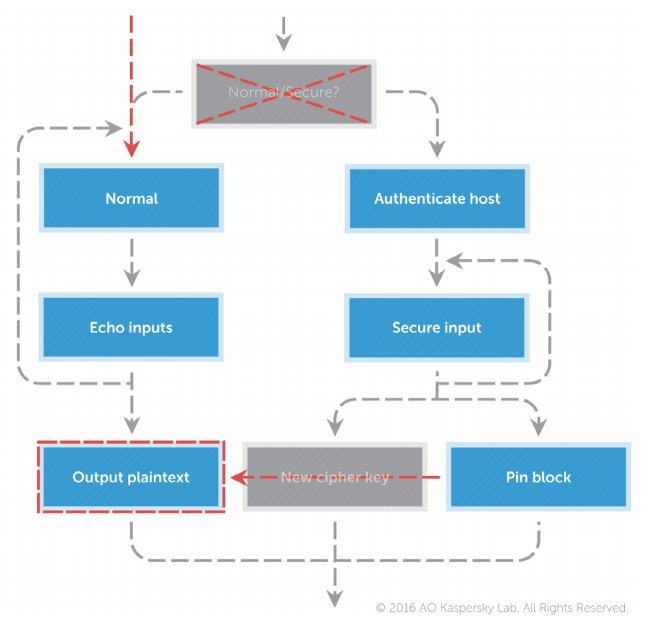

The further use of biometrics to steal funds is still questionable and is not described in detail. But there is an important nuance: if cybercriminals learn to do this, we will get an analogue of the situation with cloned credit cards, but without the possibility of “re-issuance” (fingerprints, voice, etc.). It is not a fact that fingerprint simulators will have to be invented: a separate chapter of the study provides scenarios for attacks on PIN pads, during which data can be intercepted or replaced, with encryption being forced to be disabled. Is it possible to implement this for a biometric sensor? Why not.

The report does not address the issue of outdated hardware in ATMs - although this poses a certain security problem, solutions exist even for ancient devices. In general, a comprehensive approach to threat scenarios involves an equally multidirectional list of measures to prevent them. In at least three areas: network, software and hardware (plus it is advisable not to forget about training for staff). For all three, there is an obvious need for secure data transfer at all stages and authentication verification - otherwise situations become possible when a “foreign” control module is simply connected to the cash dispenser. Separately, the software part offers strict control over the launch of unauthorized code: for ATMs, unlike ordinary computers, this is relatively easy to implement. Finally, at the network level, it is necessary to isolate network segments from each other: so that quite common situations do not arise when an ATM is directly accessible from the Internet as a result of a configuration error.

Guess the axis according to Adobe Reader

Although some of the attack scenarios shown in the report are (for now) theoretical, together with the “practical” ones they add up to an interesting picture. Financial organizations have to deal with both specific threats (attack on SWIFT, Carbanak - hacking with knowledge of internal processes) and common ones (phishing, exploitation of vulnerabilities, configuration errors, and so on). Let’s add here traditional skimmers, physical hacking of ATMs, difficulties with updating software and hardware (my own proof is in the photo above). On the one hand, all this results in one gigantic vulnerability. On the other hand, there are also a lot of resources for defense, be it monetary or expert. So the financial sector in the future may bring us both new examples of high-profile cyber hacks and truly innovative security models.

Disclaimer: This column is based on real events, but still reflects only the personal opinion of its author. It may or may not coincide with the position of Kaspersky Lab. It depends on your luck.

There are many scenarios when something can go wrong with an ATM, and most are based not on a theoretical analysis of potential vulnerabilities, but on the practice of analyzing real attacks. The banking industry as a whole is much more secure than other industries, but cybercriminals also pay more attention to it: real money is at stake. Nevertheless, it would be nice to somehow systematize the weak points of the banking infrastructure, which is what Laboratory specialists Olga Kochetova and Alexey Osipov recently did.

As with the history of the investigation into the Lurk campaign, this text is a free retelling of the primary sources. I send them for details: this is a review article on Securelist in Russian, a study “Future scenarios of attacks on communication systems interacting with ATMs” in English, a brief summary from there - only a description of attacks and countermeasures, as well as earlier publications: a description of the malware Skimer and targeted attacks on Tyupkin ATMs .

Do you remember how it all began

Attacks on ATMs are not an entirely new topic. The first version of the Skimer malware appeared in 2008-2009. The attack is aimed directly at ATMs: in one of the current versions (Skimer exists and is still being developed today), after an ATM is infected, it can be controlled by inserting a prepared card with a “key” on a magnetic stripe into the ATM.

His brilliance!

True to its name, Skimer can enable the collection of data from cards inserted into an ATM, but it can also be used to directly steal cash - the corresponding command is provided in the control menu. Skimer is embedded in the legitimate SpiService.exe process, resulting in full access to XFS, a universal client-server architecture for financial applications on Windows systems.

Unlike Skimer, the Tyupkin attack, studied in the Lab in 2014, does not use prepared cards. Instead, the malicious code is activated at a certain time of the day, and even at this time, it is possible to intercept control of the ATM only after entering a dynamic authorization code. The consequences of a successful attack, however, are approximately the same:

Carbanak and company

Actually, the most interesting thing in these two examples is the infection process, which sometimes has to be reconstructed from CCTV camera recordings. In the case of Tyupkin, the malware was installed from a CD (!), meaning there was physical access to the insides of the ATM. This is an obvious attack vector with equally obvious disadvantages. But he is not the only one.

In the Carbanak campaign, the details of which were revealed by Laboratory experts in February last year, ATMs are used as a last resort, silently giving away the cash upon command from the center, without any on-site manipulation. The infrastructure of the victims was compromised, thanks to which the main damage was caused, as they say, by bank transfer. When losses are measured in hundreds of millions of dollars, cash ceases to play a significant role.

The trend continued to develop this year: in February, we reported on three new attacks, two of which were aimed at non-cash theft of funds. Only one campaign (Metel) involved withdrawing funds through ATMs, but no one hacked the devices themselves. Technically, the transaction (withdrawal of money from the account) was legitimate, but after it the card balance rolled back to its previous value. The modern version of the irredeemable nickel was operated, as in the case of other attacks, at night, preferably on weekends.

Cybercriminals will attack the root infrastructure of financial institutions as long as they have the opportunity, that is, while it is vulnerable. As the story of the robbery through the SWIFT interbank transfer system shows , even critical elements of the financial infrastructure are not always properly protected (isn’t it true that ATM protection is sometimes better?). I would like to believe that this will not last long. Considering that cybercrime about ATMs is never forgotten, they are the ones who claim the dubious privilege of a long-term headache for the financial industry.

Which direction should we be afraid?

In their analysis of future vectors of attacks on ATMs, our experts are not limited to direct cash theft. To this clear goal, let’s add the theft of customer data for the subsequent withdrawal of funds in larger volumes with less chance of being caught on a surveillance camera. But that's not all. If you look closely, you won’t be able to find a place in the entire IT “connection” of the ATM network that cannot be attacked.

An interesting example is biometric customer identification - a relatively new technology that allows you to either replace or supplement standard means of authorization - using a PIN code, using NFC, and so on. The theft of biometric data is theoretically possible through appropriately modified skimmers (if biometrics once again fails the previous mistakes with card readers), through a Man-in-the-middle attack (when an ATM starts sending data to someone else’s processing server), or through an attack on the infrastructure of a financial organization.

The further use of biometrics to steal funds is still questionable and is not described in detail. But there is an important nuance: if cybercriminals learn to do this, we will get an analogue of the situation with cloned credit cards, but without the possibility of “re-issuance” (fingerprints, voice, etc.). It is not a fact that fingerprint simulators will have to be invented: a separate chapter of the study provides scenarios for attacks on PIN pads, during which data can be intercepted or replaced, with encryption being forced to be disabled. Is it possible to implement this for a biometric sensor? Why not.

What to do?

The report does not address the issue of outdated hardware in ATMs - although this poses a certain security problem, solutions exist even for ancient devices. In general, a comprehensive approach to threat scenarios involves an equally multidirectional list of measures to prevent them. In at least three areas: network, software and hardware (plus it is advisable not to forget about training for staff). For all three, there is an obvious need for secure data transfer at all stages and authentication verification - otherwise situations become possible when a “foreign” control module is simply connected to the cash dispenser. Separately, the software part offers strict control over the launch of unauthorized code: for ATMs, unlike ordinary computers, this is relatively easy to implement. Finally, at the network level, it is necessary to isolate network segments from each other: so that quite common situations do not arise when an ATM is directly accessible from the Internet as a result of a configuration error.

Guess the axis according to Adobe Reader

Although some of the attack scenarios shown in the report are (for now) theoretical, together with the “practical” ones they add up to an interesting picture. Financial organizations have to deal with both specific threats (attack on SWIFT, Carbanak - hacking with knowledge of internal processes) and common ones (phishing, exploitation of vulnerabilities, configuration errors, and so on). Let’s add here traditional skimmers, physical hacking of ATMs, difficulties with updating software and hardware (my own proof is in the photo above). On the one hand, all this results in one gigantic vulnerability. On the other hand, there are also a lot of resources for defense, be it monetary or expert. So the financial sector in the future may bring us both new examples of high-profile cyber hacks and truly innovative security models.

Disclaimer: This column is based on real events, but still reflects only the personal opinion of its author. It may or may not coincide with the position of Kaspersky Lab. It depends on your luck.

Last edited: