Tomcat

Professional

- Messages

- 2,687

- Reaction score

- 1,038

- Points

- 113

As you know, the history of modern bank cards begins in 1960 with the iron of Mrs. Perry, the wife of IBM engineer Forrest Perry. He could not glue a strip of tape to a plastic card, either the glue did not hold it, or it warped so that it was impossible to play the recording on it. And then his wife Dorothea, who was ironing clothes and heard her husband swearing at the rebellious magnetic tape, advised him: “Try it with an iron!” He tried it, ironed the card, and the magnetic tape was welded tightly to it. This is how the bank card we use today was born.

Today, the number of bank cards in the world exceeds the population of the globe, and a business of this scale cannot exist without its own mythology and apocryphal shrines such as the Holy Grail - in this case, Dorothea Perry's iron. However, the iron could have been completely real, and a similar conversation between the spouses also probably took place exactly like what is now being described in detail by both professional historians of science and technology and amateur enthusiasts. True, there are nuances here.

A graduate of Southern Utah University (SUU), Forrest Perry worked as an engineer at IBM Minnesota in 1957, where he was responsible for the development of new computer technologies and electronic devices. He already had the technology for optical computer reading of digital and bar codes. And in 1960, he worked on a magnetic version of ID for the plastic identification cards of CIA employees instead of a bar code. In 2004, a year before his death, Forrest Perry was awarded the SUU Alumni Award for this achievement, that is, included in the list of the most outstanding graduates of Southern Utah University.

And in the same 1960s, the actual payment cards with magnetic media were worked on by a group of IBM engineers led by engineer Jerome Svigals in another branch of the corporation in California in the town of Los Gatos (now part of the Silicon Valley agglomeration). In the May 30, 2012 issue of IEEE Spectrum magazine, his article “On the Long Life and Inevitable Death of Magnetic Stripe Cards” was published, which is worth reading for anyone interested in the history of payment cards. In it, Svigals, among other things, writes about two things that are interesting to us.

Firstly, Svigals recalls, having made sure of the correct choice of magnetic tape as an information carrier, the engineers of his group were faced with the problem of the mechanical strength of the card, which at that time was a piece of cardboard with a magnetic strip glued to it literally with adhesive tape. Mrs. Forrest Parry's iron solved this problem; more precisely, it indicated the direction in which to work. Parry published the results of his work on the plastic magnetic ID card in the corporate bulletin ((FC Parry, ''IBM Technical Disclosure Bulletin'', "Identification Card", Vol. 3, No. 6, November 6, 1960, page 8), and they were known in the California branch of the company.

But it took IBM engineers more than two years to create a machine similar to Dorothea Perry's iron, which could stamp magnetic stripes onto cards at a high speed and with sufficient reliability at a temperature of 160 °C. However, the price of issuing one card was two dollars, which is approximately equal to eleven today’s dollars, that is, simply put, it was exorbitant. It took a whole decade, until 1980, to reduce it to an acceptable five cents per card, writes Jerome Svigals. Today, issuing one card costs two to three cents. In other words, no matter how funny it looks now, it took twice as long to bring Mrs. Parry’s iron to the industrial stamping conveyor-automatic machine for the production of bank card blanks than it took for all the sophisticated IT technologies for encrypting data on a magnetic stripe, protecting them and reading.

The second important detail of the history of the magnetic payment card, which Svigals writes about, is that IBM “did not even patent the card they invented with machine-readable information. On the contrary, they allowed everyone to use this technology free of charge, in the expectation that the more operations are performed using machine-readable storage media, the more computers will be sold to work with them. The strategy exceeded all expectations: by 1990, for every dollar IBM spent on developing magnetic stripe cards, it generated $1,500 in computer sales."

In 2011, already at a very advanced age, Jerome Svigals on the Reddit website set a date and time for a chat, during which he answered questions from everyone who was interested in the history of the invention of bank cards. There, perhaps, more briefly and clearly than in any other publications, both in special and popular sources, the essence of the invention of a payment card with a magnetic stripe is stated, and not only that.

But first, a few words about the state of the lending system at that time, that is, the 1960s. The very idea of lending is as old as the world. If you don’t look too deeply into its history, then in modern times, during the era of the Industrial Revolution, the most common “payment card” was a line in the expense book of a factory store, where the debts of a worker who took food and essential goods against future wages were recorded. Here everything was under control and did not require anything more from the lender than a quill pen and an inkwell, and from the person being credited a PIN code in the form of his signature or a cross, if he was illiterate, in the corresponding line of the barn book.

The expansion of this principle beyond the closed community of a single enterprise required more sophisticated ways of monitoring the creditworthiness of those buying something on credit. For example, at gas stations, customers were given tin tokens with numbers, the imprint of which on the payment receipt was then sent to the customer’s bank. Then payment cards appeared, outwardly similar to modern ones, but this was only an ID of the client’s identity, not his money. It is clear that under this condition, any lending system in the pre-computer era, with its ability to operate almost instantly with huge amounts of data, had a limitation in scale. For example, it was limited to a specific store (chain of stores), restaurant (chain of restaurants), other suppliers of goods and services and a specific bank (or banks), with which the merchant had a system for the fastest possible verification of the client’s creditworthiness (through telephone calls, teletype communications and, finally, simply manual checks by bank clerks of bills delivered by courier to the bank at the end of the day).

As banking has become computerized, these boundaries have been pushed further. And when in 1967, one of the world leaders in this field, IBM Corporation, received an order from a consortium of airlines for a system of mass non-cash purchase of air tickets by passengers, that is, people from different cities, clients of different banks, which was vital for their business, then IBM already had a promising tool in the form of a magnetic card, which made it possible to cope with this task.

As Jerome Svigals wrote in his Reddit chat: “It was a magnetic stripe that involved four of our achievements. The first step was to make the magnetic material as reliable and economical as paper. Secondly, we were dealing with two different industries - banking and airlines. Banking was carried out on a digital system, while airlines operate on an alphabetic system. Meeting these two requirements simultaneously was a huge challenge. The magnetic stripe had two tracks: the first contained alphabetic information for airline and government use, and the second track was numeric for retail banking. The third track, in principle optional, was intended for dubbing. The third problem we faced was how to make them secure, since they were initially easy to manipulate.

We decided to implement security algorithms in the processing system (that is, the terminal of the ticket vending machine - Ed.), and not in the card, which turned out to be extremely effective. The fourth problem was the volatility of the banking system. Since banking technology changes significantly every ten years or so, we had to ensure that the entries on the card strip changed too. We solved this problem by maintaining the same industry-specific processing structure while changing the way the card communicates information. This still applies today to smartphones because the chips in phones, which are essentially computers, now store this information. This system lasted 40-50 years so that's quite an achievement and I expect it to last longer. That's what I call setting a precedent!"

Svigals had a total of 15 patents throughout his life, but, as already mentioned, the company decided not to patent this “precedent” created by his group of engineers at IBM. Svigals himself, either jokingly or seriously, wrote about this many years later: “I don’t regret it. What I seriously regret is that at one time I did not think of investing more of my money in my company’s computer technologies.”

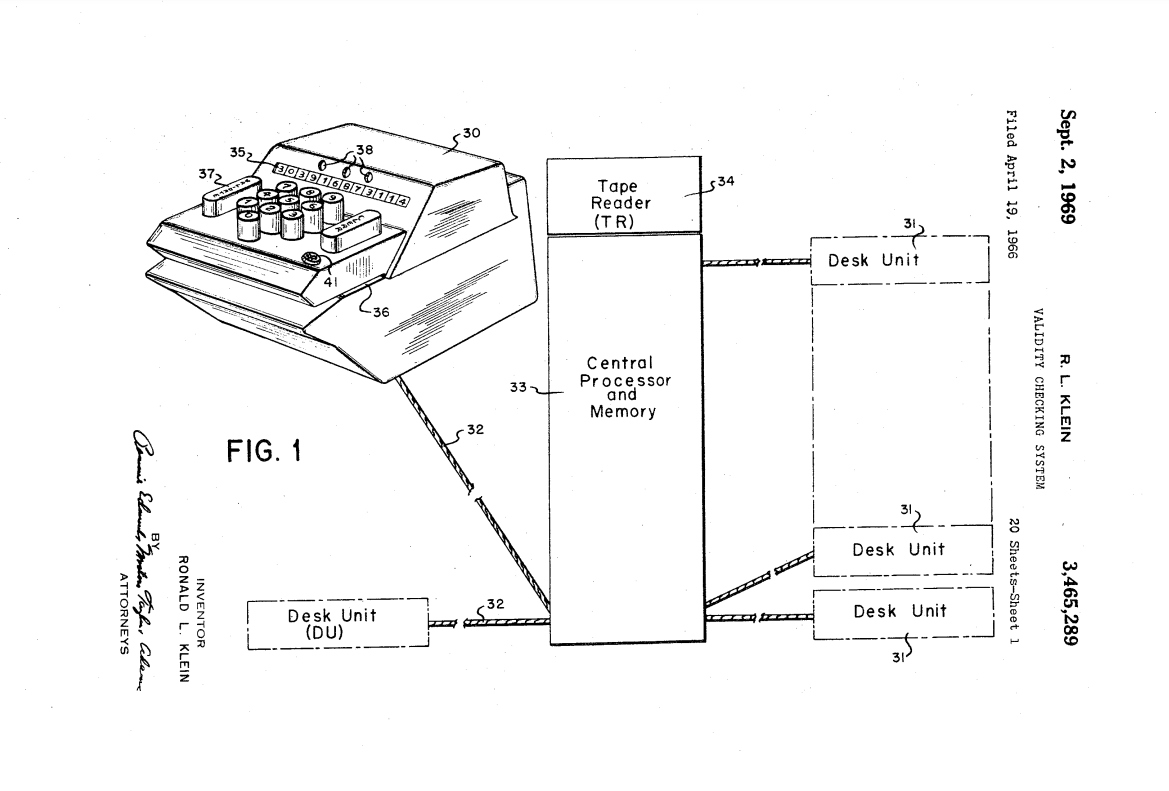

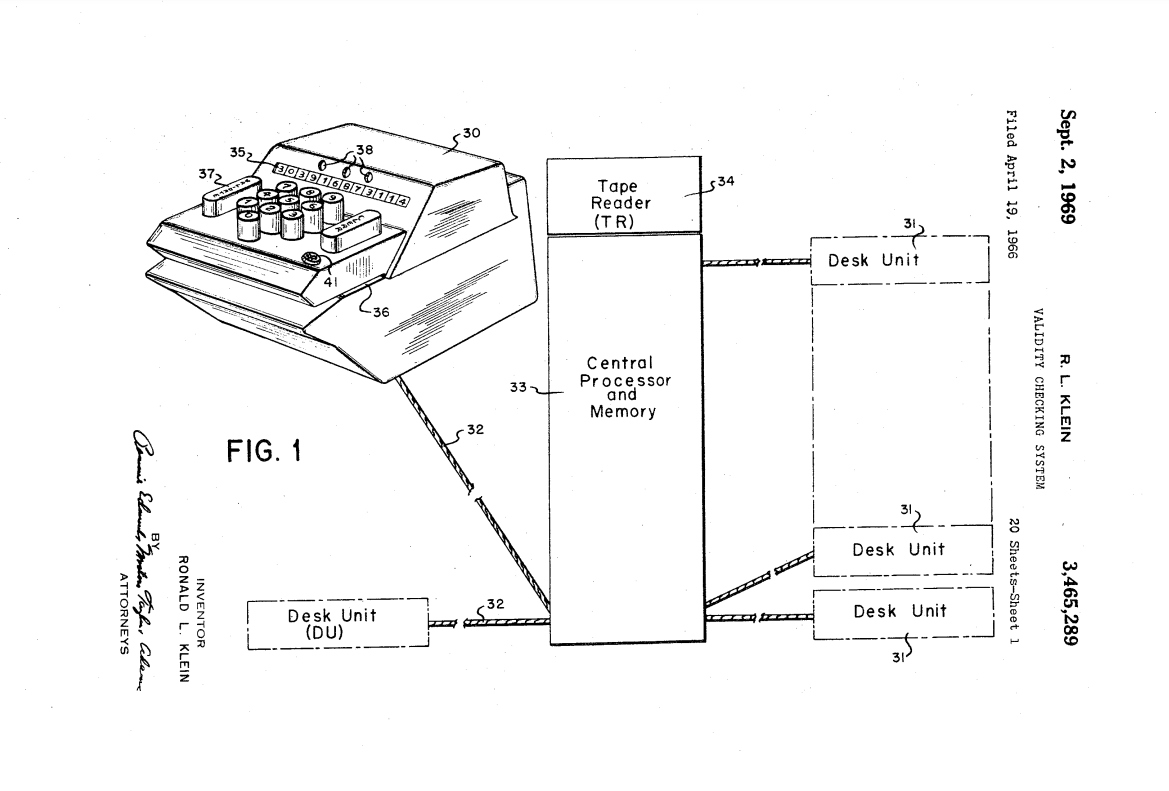

Publications on the history of payment cards often mention Ron Klein, a very prolific inventor, author of about 200 patent applications, and in the 1960s, director of engineering at Ultronics Systems Corporation. In 1966, Klein filed a patent application, and in 1969 received patent US3465289A , as they write, for a magnetic card. But it's easy to read the application and see that it's actually about a "desktop interrogation device" that allowed merchants to check credit card numbers against a database of credit card numbers that would be stored in the device's memory, and if the account number on the card was not in the “bad” list, the “credit good” indicator on the desktop device would light up. Klein's device was also applicable to operating a vending machine and dispensing coins or paper currency using an encrypted ID or credit card or other means of personal identification. That is, we are talking here more about a terminal or ATM, and not about a bank card. Moreover, Klein’s patent application talks a lot about plans to create a “magnetic tape reader,” that is, again, about terminals or ATMs.

The magnetic card itself was not a miracle or a revelation, its idea had been in the air for a long time, and it was also very clear to everyone that its maintenance would require an appropriate infrastructure, including a common and agreed standardization of writing and reading data on the magnetic tape of the card, well , of course, terminals and ATMs for these cards. This infrastructure was created in different countries throughout the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. As for the magnetic card itself and IBM’s “noble” refusal to patent it, the question involuntarily arises: what could actually be patented here?

The idea of magnetic recording on iron wire, steel tape and even cotton thread and paper tape coated with iron oxide was patented by the Dane Waldemar Poulsen at the end of the 19th century, and polymer tape by the German company BASF in the 1930s. IBM's know-how was only encryption algorithms on magnetic tape tracks, but if there was an acute reluctance to buy a license for them, it was possible to change them without damaging the final result; this was a question of cryptography, not technology.

Today, the number of bank cards in the world exceeds the population of the globe, and a business of this scale cannot exist without its own mythology and apocryphal shrines such as the Holy Grail - in this case, Dorothea Perry's iron. However, the iron could have been completely real, and a similar conversation between the spouses also probably took place exactly like what is now being described in detail by both professional historians of science and technology and amateur enthusiasts. True, there are nuances here.

A graduate of Southern Utah University (SUU), Forrest Perry worked as an engineer at IBM Minnesota in 1957, where he was responsible for the development of new computer technologies and electronic devices. He already had the technology for optical computer reading of digital and bar codes. And in 1960, he worked on a magnetic version of ID for the plastic identification cards of CIA employees instead of a bar code. In 2004, a year before his death, Forrest Perry was awarded the SUU Alumni Award for this achievement, that is, included in the list of the most outstanding graduates of Southern Utah University.

And in the same 1960s, the actual payment cards with magnetic media were worked on by a group of IBM engineers led by engineer Jerome Svigals in another branch of the corporation in California in the town of Los Gatos (now part of the Silicon Valley agglomeration). In the May 30, 2012 issue of IEEE Spectrum magazine, his article “On the Long Life and Inevitable Death of Magnetic Stripe Cards” was published, which is worth reading for anyone interested in the history of payment cards. In it, Svigals, among other things, writes about two things that are interesting to us.

Firstly, Svigals recalls, having made sure of the correct choice of magnetic tape as an information carrier, the engineers of his group were faced with the problem of the mechanical strength of the card, which at that time was a piece of cardboard with a magnetic strip glued to it literally with adhesive tape. Mrs. Forrest Parry's iron solved this problem; more precisely, it indicated the direction in which to work. Parry published the results of his work on the plastic magnetic ID card in the corporate bulletin ((FC Parry, ''IBM Technical Disclosure Bulletin'', "Identification Card", Vol. 3, No. 6, November 6, 1960, page 8), and they were known in the California branch of the company.

But it took IBM engineers more than two years to create a machine similar to Dorothea Perry's iron, which could stamp magnetic stripes onto cards at a high speed and with sufficient reliability at a temperature of 160 °C. However, the price of issuing one card was two dollars, which is approximately equal to eleven today’s dollars, that is, simply put, it was exorbitant. It took a whole decade, until 1980, to reduce it to an acceptable five cents per card, writes Jerome Svigals. Today, issuing one card costs two to three cents. In other words, no matter how funny it looks now, it took twice as long to bring Mrs. Parry’s iron to the industrial stamping conveyor-automatic machine for the production of bank card blanks than it took for all the sophisticated IT technologies for encrypting data on a magnetic stripe, protecting them and reading.

The second important detail of the history of the magnetic payment card, which Svigals writes about, is that IBM “did not even patent the card they invented with machine-readable information. On the contrary, they allowed everyone to use this technology free of charge, in the expectation that the more operations are performed using machine-readable storage media, the more computers will be sold to work with them. The strategy exceeded all expectations: by 1990, for every dollar IBM spent on developing magnetic stripe cards, it generated $1,500 in computer sales."

In 2011, already at a very advanced age, Jerome Svigals on the Reddit website set a date and time for a chat, during which he answered questions from everyone who was interested in the history of the invention of bank cards. There, perhaps, more briefly and clearly than in any other publications, both in special and popular sources, the essence of the invention of a payment card with a magnetic stripe is stated, and not only that.

But first, a few words about the state of the lending system at that time, that is, the 1960s. The very idea of lending is as old as the world. If you don’t look too deeply into its history, then in modern times, during the era of the Industrial Revolution, the most common “payment card” was a line in the expense book of a factory store, where the debts of a worker who took food and essential goods against future wages were recorded. Here everything was under control and did not require anything more from the lender than a quill pen and an inkwell, and from the person being credited a PIN code in the form of his signature or a cross, if he was illiterate, in the corresponding line of the barn book.

The expansion of this principle beyond the closed community of a single enterprise required more sophisticated ways of monitoring the creditworthiness of those buying something on credit. For example, at gas stations, customers were given tin tokens with numbers, the imprint of which on the payment receipt was then sent to the customer’s bank. Then payment cards appeared, outwardly similar to modern ones, but this was only an ID of the client’s identity, not his money. It is clear that under this condition, any lending system in the pre-computer era, with its ability to operate almost instantly with huge amounts of data, had a limitation in scale. For example, it was limited to a specific store (chain of stores), restaurant (chain of restaurants), other suppliers of goods and services and a specific bank (or banks), with which the merchant had a system for the fastest possible verification of the client’s creditworthiness (through telephone calls, teletype communications and, finally, simply manual checks by bank clerks of bills delivered by courier to the bank at the end of the day).

As banking has become computerized, these boundaries have been pushed further. And when in 1967, one of the world leaders in this field, IBM Corporation, received an order from a consortium of airlines for a system of mass non-cash purchase of air tickets by passengers, that is, people from different cities, clients of different banks, which was vital for their business, then IBM already had a promising tool in the form of a magnetic card, which made it possible to cope with this task.

As Jerome Svigals wrote in his Reddit chat: “It was a magnetic stripe that involved four of our achievements. The first step was to make the magnetic material as reliable and economical as paper. Secondly, we were dealing with two different industries - banking and airlines. Banking was carried out on a digital system, while airlines operate on an alphabetic system. Meeting these two requirements simultaneously was a huge challenge. The magnetic stripe had two tracks: the first contained alphabetic information for airline and government use, and the second track was numeric for retail banking. The third track, in principle optional, was intended for dubbing. The third problem we faced was how to make them secure, since they were initially easy to manipulate.

We decided to implement security algorithms in the processing system (that is, the terminal of the ticket vending machine - Ed.), and not in the card, which turned out to be extremely effective. The fourth problem was the volatility of the banking system. Since banking technology changes significantly every ten years or so, we had to ensure that the entries on the card strip changed too. We solved this problem by maintaining the same industry-specific processing structure while changing the way the card communicates information. This still applies today to smartphones because the chips in phones, which are essentially computers, now store this information. This system lasted 40-50 years so that's quite an achievement and I expect it to last longer. That's what I call setting a precedent!"

Svigals had a total of 15 patents throughout his life, but, as already mentioned, the company decided not to patent this “precedent” created by his group of engineers at IBM. Svigals himself, either jokingly or seriously, wrote about this many years later: “I don’t regret it. What I seriously regret is that at one time I did not think of investing more of my money in my company’s computer technologies.”

Publications on the history of payment cards often mention Ron Klein, a very prolific inventor, author of about 200 patent applications, and in the 1960s, director of engineering at Ultronics Systems Corporation. In 1966, Klein filed a patent application, and in 1969 received patent US3465289A , as they write, for a magnetic card. But it's easy to read the application and see that it's actually about a "desktop interrogation device" that allowed merchants to check credit card numbers against a database of credit card numbers that would be stored in the device's memory, and if the account number on the card was not in the “bad” list, the “credit good” indicator on the desktop device would light up. Klein's device was also applicable to operating a vending machine and dispensing coins or paper currency using an encrypted ID or credit card or other means of personal identification. That is, we are talking here more about a terminal or ATM, and not about a bank card. Moreover, Klein’s patent application talks a lot about plans to create a “magnetic tape reader,” that is, again, about terminals or ATMs.

The magnetic card itself was not a miracle or a revelation, its idea had been in the air for a long time, and it was also very clear to everyone that its maintenance would require an appropriate infrastructure, including a common and agreed standardization of writing and reading data on the magnetic tape of the card, well , of course, terminals and ATMs for these cards. This infrastructure was created in different countries throughout the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. As for the magnetic card itself and IBM’s “noble” refusal to patent it, the question involuntarily arises: what could actually be patented here?

The idea of magnetic recording on iron wire, steel tape and even cotton thread and paper tape coated with iron oxide was patented by the Dane Waldemar Poulsen at the end of the 19th century, and polymer tape by the German company BASF in the 1930s. IBM's know-how was only encryption algorithms on magnetic tape tracks, but if there was an acute reluctance to buy a license for them, it was possible to change them without damaging the final result; this was a question of cryptography, not technology.