Recently, Moses Caranja, leaving Addis Ababa International Airport by taxi, faced an awkward situation: he was unable to pay his driver. As they drove into the city, a government-controlled operator in Ethiopia cut off the country's Internet. Neither Karanja nor the driver knew how much the trip was supposed to cost. He agreed with the driver about the amount that suits both. But those internet outages that followed a spate of killings of officials across the country in June prompted him to look at network outages in a different way. He suspected that some services, such as WhatsApp, did not work even after other sites "resurrected" a few days after the shutdown.

Karanja was right. Working on a project called the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), which collects internet connection data from around the world, he discovered that Facebook, Facebook Messenger and the web version of WhatsApp were blocked after the initial shutdown, making communication difficult for many Ethiopians. Services in the country were not available until recently, in August.

OONI provides information on the availability of the Internet in countries where the authorities are unlikely to ever admit that they have blocked something, says Karanja. This project is one of the few attempts to measure global online censorship, which is not always as brutal as in the Ethiopian example. Sometimes the government targets specific websites or requires video to be disabled or filtering of images, news, news feeds. All this is censorship. OONI and other projects document attempts at such censorship.

Concerns about censorship are a global phenomenon, even in countries with liberal democracies. India, with its seemingly democratic structure, turned off the internet in Kashmir several times in the summer when the ruling Hindu nationalist party demanded greater control over the Muslim-majority region.

A spate of killings of officials in Ethiopia in June resulted in internet shutdowns for several days. Michael Tewelde / Getty Images

OONI researchers use a set of network signals sent by volunteers. These signals mean little in isolation, but when put together can expose censorship. Arturo Filasto, founder of OONI, says censorship is often when the content you see on the Internet varies depending on your location. “There are many parallel Internet connections,” he notes.

The challenge for the project in authoritarian countries is to measure and track what is being blocked or removed, and why.

REGISTRATION OF PATTERNS

With the help of the open source OONI Probe, the project covers over 200 countries, including Egypt, Venezuela and Ukraine. Volunteers install the OONI Probe app on their phones, tablets, and Mac and Linux computers. The app periodically checks the preconfigured list of websites and records the response a user gets when they try to navigate to a specific site. This is how the application knows which sites are blocked or from which sites users are being redirected to others. The censor patterns registered in this way are sent to general statistics.

For example, in 2016, OONI, with the help of volunteers, investigated internet censorship in Egypt. Then it turned out that users are often redirected to pop-ups when they want to go to the website of a non-governmental organization or the media.

SOCIAL FILTERING

Online censorship isn't just about blocked sites. Social networks also filter content in news feeds and chats. In China, social media is held accountable to the government for politically inappropriate content.

Social networks filter any images in chats and news feeds that may be unpleasant for the state. Filtering standards are not always transparent and change over time. For example, Weibo, the Chinese counterpart to Twitter, has twice tried to remove LGBT content from its platform and has scrapped the idea due to unexpected public outcry. Some things can be filtered out on certain dates (for example, during important holidays or political events in the opinion of the government), and allowed later.

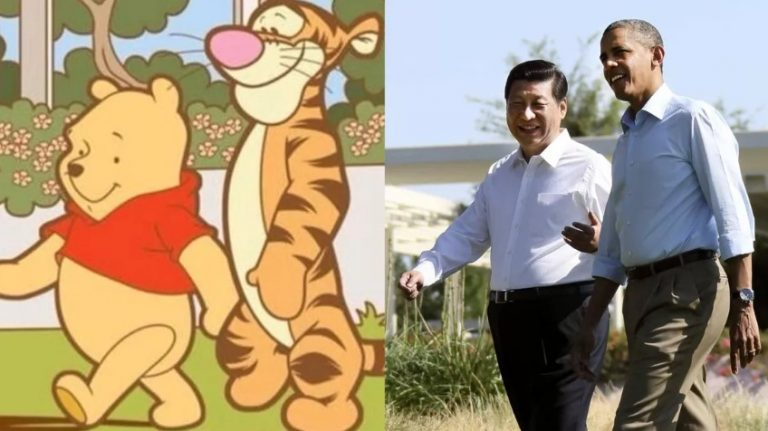

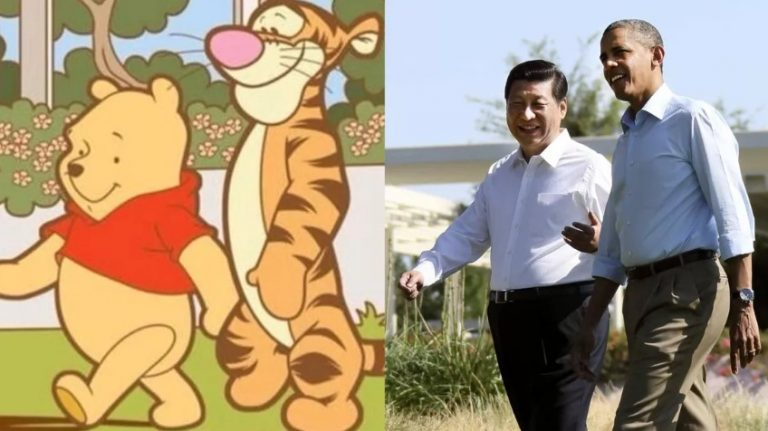

Pictures of Winnie the Pooh were removed from Chinese social networks after users compared CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping to a cartoon bear.

After researching WeChat, OONI understood how the social network automates image filtering. It turned out that the company was updating its filters in real time. Not only is the infamous photograph of a man in front of a tank from the 1989 demonstrations in Tiananmen being filtered. Photos of current news are also filtered: the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, the China-US trade war, and even the 2018 US Senate and Congressional midterm elections.

DELETE CONTENT

Content filtering takes place not only in China, but also in the United States, albeit in a slightly different sense. After users have shared hate speech and violent content on social media, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter have faced criticism and are now developing algorithms and hiring moderators to filter out inappropriate content. But here an unexpected dilemma arises. It is not always easy to say whether violent videos should be banned or retained as evidence of human rights violations.

Videos of terrorist or military violence are often filmed from social media, but they can serve as important evidence of human rights violations. The photo shows the consequences of a car explosion in Syria.

In 2017, the non-profit organization Syrian Archives discovered that YouTube had turned off about 180 channels containing hundreds of thousands of videos from Syria. The point was that video hosting introduced a new policy to eradicate violence and terrorist propaganda. One of the deleted videos showed footage of destruction at four Syrian field hospitals. The Syrian Archive then insisted that YouTube restore many of those videos, but others were lost.

According to the head of the Syrian Archive Jeff Deutsch, it is important not to block such videos, because the social network provides a good opportunity to inform society and human rights organizations about atrocities. For example, the UN Security Council referred to a Youtube video in a report on the use of chemical weapons in Ghouta, Syria.

MEASURING REALITY

After the Internet in Addis Ababa went offline, Karanja, Ph.D. from the University of Toronto, decided to leave the country, as without the Internet he could not contact foreign colleagues. So he flew to neighboring Kenya and worked from there. True, in Kenya, the consequences of the Ethiopian shatdaun overtook him.

He tried to call his Ethiopian contacts in Kenya on WhatsApp, but could not - the service was intermittent. Therefore, I had to use regular cellular communications, which cost 100 times more.

All these inconveniences worried Karanja. But he decided that he was still lucky. “This is my story: monetary losses and inconveniences. There are people who have experienced much more. "

Karanja was right. Working on a project called the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), which collects internet connection data from around the world, he discovered that Facebook, Facebook Messenger and the web version of WhatsApp were blocked after the initial shutdown, making communication difficult for many Ethiopians. Services in the country were not available until recently, in August.

OONI provides information on the availability of the Internet in countries where the authorities are unlikely to ever admit that they have blocked something, says Karanja. This project is one of the few attempts to measure global online censorship, which is not always as brutal as in the Ethiopian example. Sometimes the government targets specific websites or requires video to be disabled or filtering of images, news, news feeds. All this is censorship. OONI and other projects document attempts at such censorship.

Concerns about censorship are a global phenomenon, even in countries with liberal democracies. India, with its seemingly democratic structure, turned off the internet in Kashmir several times in the summer when the ruling Hindu nationalist party demanded greater control over the Muslim-majority region.

A spate of killings of officials in Ethiopia in June resulted in internet shutdowns for several days. Michael Tewelde / Getty Images

OONI researchers use a set of network signals sent by volunteers. These signals mean little in isolation, but when put together can expose censorship. Arturo Filasto, founder of OONI, says censorship is often when the content you see on the Internet varies depending on your location. “There are many parallel Internet connections,” he notes.

The challenge for the project in authoritarian countries is to measure and track what is being blocked or removed, and why.

REGISTRATION OF PATTERNS

With the help of the open source OONI Probe, the project covers over 200 countries, including Egypt, Venezuela and Ukraine. Volunteers install the OONI Probe app on their phones, tablets, and Mac and Linux computers. The app periodically checks the preconfigured list of websites and records the response a user gets when they try to navigate to a specific site. This is how the application knows which sites are blocked or from which sites users are being redirected to others. The censor patterns registered in this way are sent to general statistics.

For example, in 2016, OONI, with the help of volunteers, investigated internet censorship in Egypt. Then it turned out that users are often redirected to pop-ups when they want to go to the website of a non-governmental organization or the media.

SOCIAL FILTERING

Online censorship isn't just about blocked sites. Social networks also filter content in news feeds and chats. In China, social media is held accountable to the government for politically inappropriate content.

Social networks filter any images in chats and news feeds that may be unpleasant for the state. Filtering standards are not always transparent and change over time. For example, Weibo, the Chinese counterpart to Twitter, has twice tried to remove LGBT content from its platform and has scrapped the idea due to unexpected public outcry. Some things can be filtered out on certain dates (for example, during important holidays or political events in the opinion of the government), and allowed later.

Pictures of Winnie the Pooh were removed from Chinese social networks after users compared CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping to a cartoon bear.

After researching WeChat, OONI understood how the social network automates image filtering. It turned out that the company was updating its filters in real time. Not only is the infamous photograph of a man in front of a tank from the 1989 demonstrations in Tiananmen being filtered. Photos of current news are also filtered: the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, the China-US trade war, and even the 2018 US Senate and Congressional midterm elections.

DELETE CONTENT

Content filtering takes place not only in China, but also in the United States, albeit in a slightly different sense. After users have shared hate speech and violent content on social media, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter have faced criticism and are now developing algorithms and hiring moderators to filter out inappropriate content. But here an unexpected dilemma arises. It is not always easy to say whether violent videos should be banned or retained as evidence of human rights violations.

Videos of terrorist or military violence are often filmed from social media, but they can serve as important evidence of human rights violations. The photo shows the consequences of a car explosion in Syria.

In 2017, the non-profit organization Syrian Archives discovered that YouTube had turned off about 180 channels containing hundreds of thousands of videos from Syria. The point was that video hosting introduced a new policy to eradicate violence and terrorist propaganda. One of the deleted videos showed footage of destruction at four Syrian field hospitals. The Syrian Archive then insisted that YouTube restore many of those videos, but others were lost.

According to the head of the Syrian Archive Jeff Deutsch, it is important not to block such videos, because the social network provides a good opportunity to inform society and human rights organizations about atrocities. For example, the UN Security Council referred to a Youtube video in a report on the use of chemical weapons in Ghouta, Syria.

MEASURING REALITY

After the Internet in Addis Ababa went offline, Karanja, Ph.D. from the University of Toronto, decided to leave the country, as without the Internet he could not contact foreign colleagues. So he flew to neighboring Kenya and worked from there. True, in Kenya, the consequences of the Ethiopian shatdaun overtook him.

He tried to call his Ethiopian contacts in Kenya on WhatsApp, but could not - the service was intermittent. Therefore, I had to use regular cellular communications, which cost 100 times more.

All these inconveniences worried Karanja. But he decided that he was still lucky. “This is my story: monetary losses and inconveniences. There are people who have experienced much more. "