BadB

Professional

- Messages

- 2,550

- Reaction score

- 2,712

- Points

- 113

In the first part of this article, we covered in detail the structure of an ATM, how it operates, and the main types of attacks on ATMs. Now it's time to move on to the most interesting part: logical attacks.

In the second part, we'll tell you how ATMs are hacked without any fuss or fuss.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute instructions or a call to commit illegal acts. Our goal is to highlight existing vulnerabilities that can be exploited by attackers and to provide recommendations for protection. The authors assume no liability for the use of this information.

During ATM security analysis, we identify specific vulnerabilities that enable the attacks described above. Below are statistics from our research, highlighting the most common vulnerabilities that lead to cash withdrawals.

The vulnerabilities discussed below are identified by identifiers like PT-ATM-XXX: they are used in an open collection of logical attacks on ATMs prepared by our specialists. The collection contains detailed recommendations for remediating vulnerabilities and descriptions of tests for identifying them, making it useful for both ATM security engineers and security analysts. It can be accessed on GitHub and is available in four languages.

1. Attacks with external control of the dispenser (black box)

All ATM configurations analyzed contained vulnerabilities in the dispenser firmware that could allow for a black-box attack. These attacks are so named because the attacker uses an external device (a kind of black box) to directly control the dispenser. To carry out the attack, access to the ATM's service area, which houses the dispenser's connection to the system unit (hereinafter referred to as the PC), is required. By connecting the appropriate cable to their own device instead of the PC, the hacker can send control commands directly to the dispenser — unless the firmware has sufficiently protected.

Most of the vulnerabilities that allow black box attacks to be carried out are related to flaws in the dispenser's built-in encryption, but there are also other problems.

1.1. Weak encryption algorithm and other shortcomings in the implementation of cryptographic algorithms (PT-ATM-204)

Among the weaknesses associated with encryption of traffic between the PC and the dispenser, the most frequently identified was the use of a weak encryption algorithm: an attacker can exploit known vulnerabilities in the algorithms to reconstruct portions of the protected traffic and extract sensitive information from it. Other weaknesses associated with traffic encryption may include the use of an imperfect random number generation mechanism, the use of hard-coded encryption keys, and other issues requiring an attacker to examine the firmware source code.

1.2. Predictable Authentication Data (PT‑ATM-203)

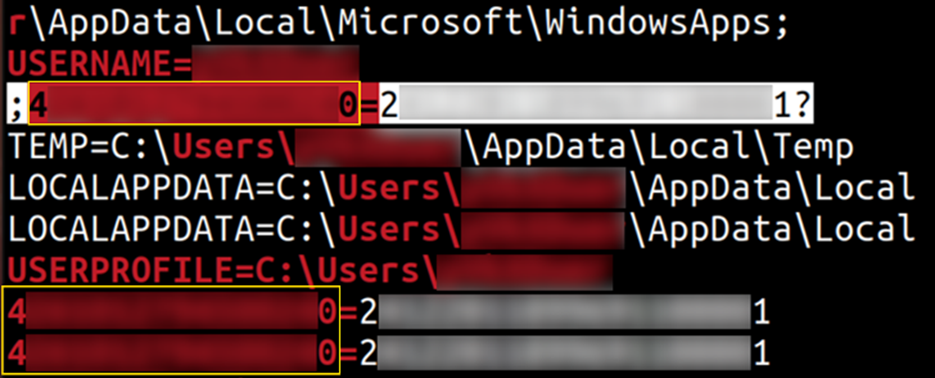

Another common flaw in dispenser firmware is the use of predictable authentication data, which is performed before information exchange between the PC and the dispenser begins. The purpose of authentication is to verify the authenticity of the source of control traffic arriving at the dispenser. This is done using information that allows the ATM PC to be unambiguously identified as genuine. Authentication data can be static values generated based on the characteristics of the PC or devices connected to it. This allows an attacker with access to the service area to reproduce the required values by analyzing the PC configuration.

Furthermore, authentication data is often present during unencrypted data exchange, making it possible to extract it from USB traffic between the PC and the dispenser by eavesdropping.

1.3. Other vulnerabilities in the dispenser software (PT‑ATM-206)

One of the common issues associated with dispenser firmware is an insecure update delivery and authentication mechanism. In most of the configurations studied, these mechanisms were found to be unreliable — an attacker could inject arbitrary control code into them. Loading such an update into the firmware could lead to both the payment of funds and the disabling of built-in security mechanisms. For example, in some configurations studied, this allowed the signature checks of commands transmitted to the dispenser to be disabled.

Another way to bypass built-in firmware security mechanisms is through buffer overflow. By sending a specially crafted data packet to the dispenser firmware that exceeds the maximum allowed size, an attacker can overwrite the function's stack with their own values.

Recommendations for protection against black box attacks:

2. Gaining access to the ATM operating system (bypassing kiosk mode)

Before we move on to the following attacks, it's important to discuss the methods for gaining access to the ATM operating system. Unless we're talking about black-box attacks, which require a direct connection to the equipment, this step is essential: the average user is unable to fully interact with the ATM and is limited to the interface offered by the kiosk app. Below, we describe vulnerabilities that allow a hacker to bypass kiosk mode and execute operating system commands on the ATM while only having access to the service area.

2.1. No hard drive encryption (PT‑ATM-231)

The lack of hard drive encryption stands out among the weaknesses open to an attacker with access only to the service area. This is because not only is this flaw one of the most common and can be exploited to gain initial access to the OS, but it also allows for the simplest possible theft of funds, which takes no more than 10 minutes.

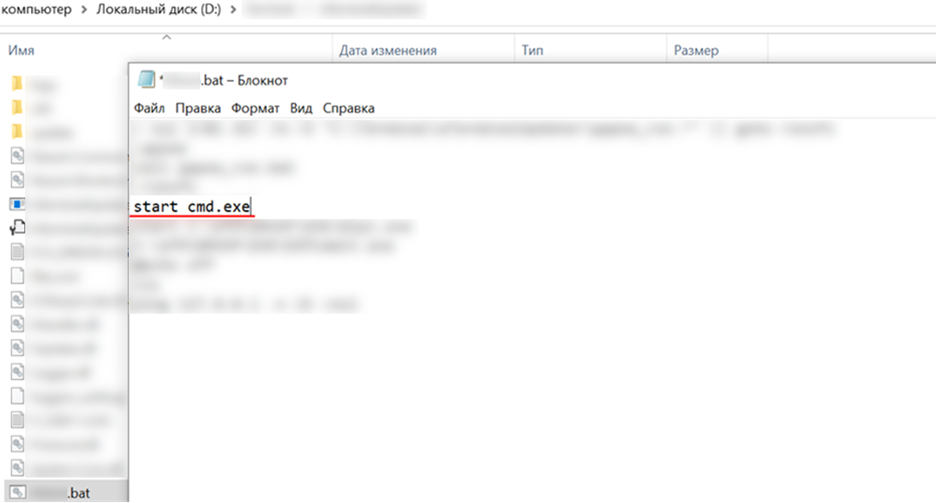

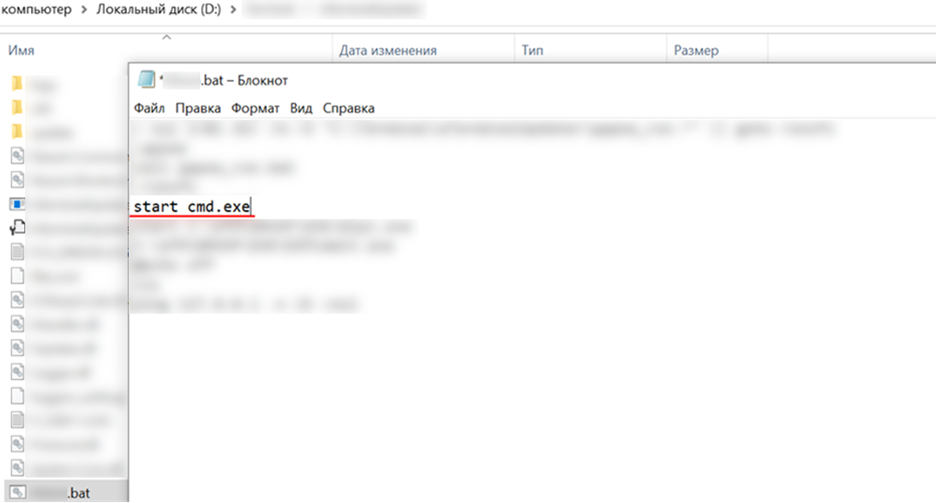

A simple example of gaining access to the operating system: while examining the contents of an unencrypted hard drive, specialists discovered a BAT file that was executed after the system fully boots up when the ATM was turned on. The line "start cmd.exe" was added to the file, causing the command line interpreter to launch after the ATM reboot. This allowed the attacker to execute operating system commands.

Modifying the BAT file after connecting a hard drive

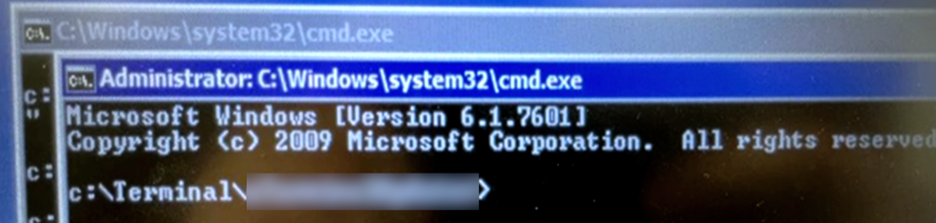

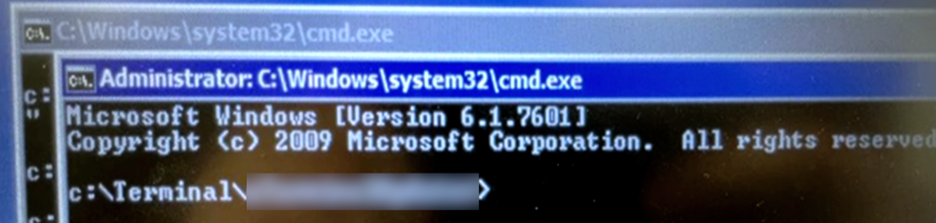

Launching a command line interpreter as a result of running a script

However, the capabilities of direct access to a hard drive are not limited to this brief example. The high risk of this flaw stems from the fact that, having gained access to the hard drive, a hacker can both install malware on it and modify configuration files to bypass security measures.

Furthermore, access to a hard drive can be an intermediate step in more complex cash theft scenarios. For example, exploiting vulnerabilities in an ATM's software requires knowledge of its operating principles. Obtaining the source code of the software is difficult for an external attacker; studying the executable files using a specialized decompiler may be the most accessible option. The lack of hard drive encryption allows a hacker to copy the software's executable files to a workstation for further study in a more secure environment.

Although the lack of hard drive encryption is a dangerous flaw, its statistics have not improved for several years. Using encryption could not only prevent the simplest method of stealing money but also complicate other attacks that exploit UPR vulnerabilities and bypass security measures.

2.2. Insufficient control of USB device connections (PT‑ATM-004) and insecure configuration of the key whitelist (PT‑ATM-001)

While connecting USB drives to ATMs is often restricted (for example, on some devices, this action is only available to administrators), connecting third-party USB keyboards is generally not prohibited. It's worth noting upfront that this also means connecting other devices recognized by the computer as belonging to the USB HID class (such as the compact Rubber Ducky and Flipper Zero).

One of the drawbacks directly related to connecting a keyboard to an ATM is the ability to exit kiosk mode using keyboard shortcuts. Insufficient restrictions on the most common shortcuts allow access to applications that should not be available to the user during normal ATM operation. For example, a default browser (such as Internet Explorer or Edge) can be used to open Windows Explorer and then launch a command prompt.

2.3. Direct Memory Access (PT‑ATM-232)

As previously mentioned, devices can be connected to the ATM system unit using USB, Ethernet, PCI, and COM interfaces. If the ATM motherboard has a free PCI slot, an attacker can attempt a direct memory access (DMA) attack.

The attack utilizes a DMA card installed in the ATM slot (for example, one based on PCILeech software or a similar tool) to directly access the device's memory, bypassing the operating system's protection mechanisms. This allows data to be read from memory, including payment information transmitted to the ATM, and arbitrary code to be injected directly into memory. Essentially, a DMA attack allows an attacker to execute OS commands with kernel privileges. Thus, a DMA attack allows privileged access to the ATM's operating system, opening up even more opportunities for unauthorized actions.

As an example, the image below shows a RAM dump containing a bank account number (PAN) - a 16-digit sequence highlighted in yellow.

A dump of the attacked device's RAM, obtained using PCILeech

Recommendations for preventing access to the OS:

3. Attacks on vulnerabilities in control software

3.1. Insecure implementation of file integrity control of control software (PT‑ATM-417)

By bypassing kiosk mode, a hacker can perform actions on behalf of a service user (this account is used by the ATM to perform functions, such as launching a banking application in kiosk mode). The attacker can attempt to dispense cash using malicious tools that target the ATM's ATM.

As mentioned earlier, the UPO controls ATM peripherals using the CEN/XFS standard. The open nature of this standard not only facilitates the spread of generic malware but also poses a threat to the UPO, which has issues with integrity control of executable and configuration files.

During our research, we found insecure implementation of UPO file integrity monitoring in most of the configurations examined. This flaw can manifest itself in various ways — for example, if the UPO:

3.2. Insufficient protection against reflection attacks (PT‑ATM-417)

The UPR analyzed by the specialists was written in just-in-time (JIT) compiled languages. Some of these, including C#, have reflection capabilities: a program can analyze its structure at runtime, dynamically invoke methods, modify object state, and access type metadata. Reflection can be exploited by hackers: insufficient integrity checking of executable files allows for an attack, to which most of the analyzed configurations were vulnerable.

It's worth noting that performing a reflection attack requires a high level of skill from the attacker: they must write an exploit for a specific implementation of the UPR. Before developing an exploit, it's essential to understand the UPR's operating principles. If the application's source code is unavailable, specialized decompilers and debuggers, such as dnSpy (for C#), are used.

3.3. Bypassing third-party software launch controls (PT-ATM-019)

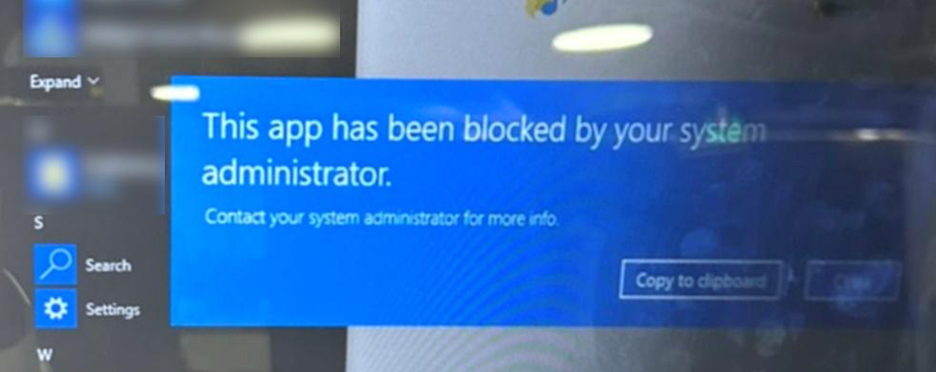

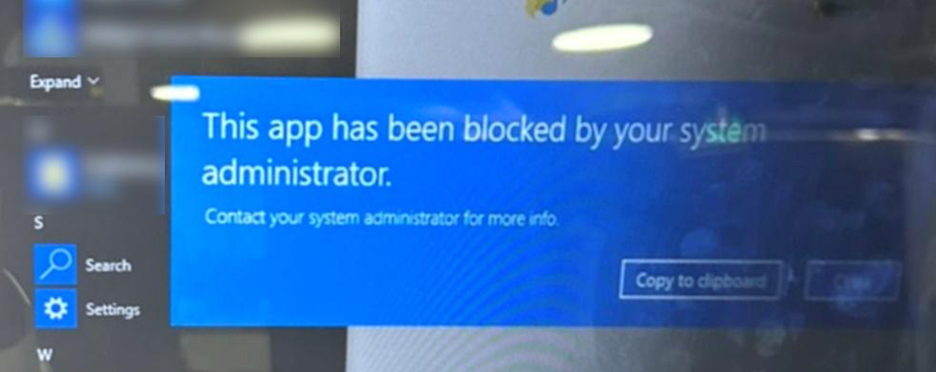

Another potential obstacle may be software restrictions — for example, prohibiting the use of command-line interpreters, which are necessary for interacting with malware. On Windows-based ATMs, solutions such as AppLocker or software restriction policies (SRPs) are often used for blocking. Third-party Application Control solutions are also possible.

Blocking the launch of certain software (for example, the command line interpreters cmd.exe and powershell.exe) is often accomplished using a blacklist, which includes standard paths to executable files. The first obvious drawback of this method is the ability to launch third-party software not on the blacklist, including malware. Another drawback is that bypassing the blocking requires launching the executable file from an alternative location. In the simplest case, this can be accomplished using Windows Explorer.

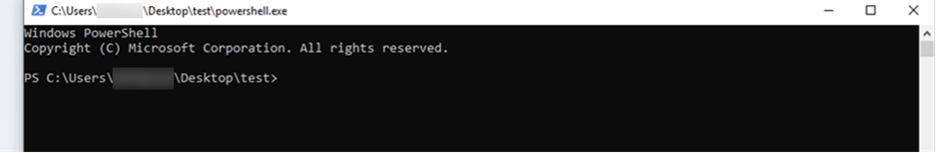

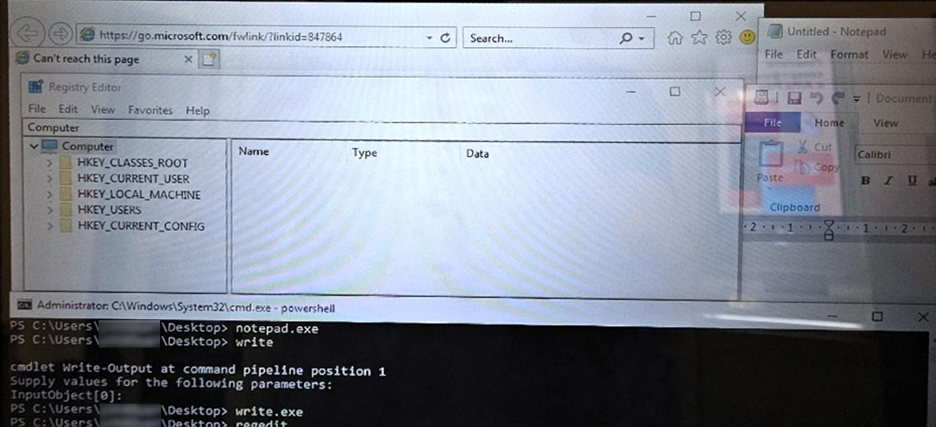

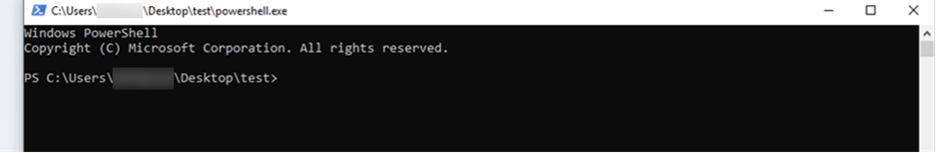

As a demonstration, we used AppLocker to block PowerShell from running from the C:\Windows\System32\Windows\PowerShell\v1.0 directory. To bypass the block, the specialists copied the powershell.exe executable file to the service user's desktop and then ran the file from the new location.

Block PowerShell from running according to an AppLocker rule

Launching PowerShell from a non-standard location

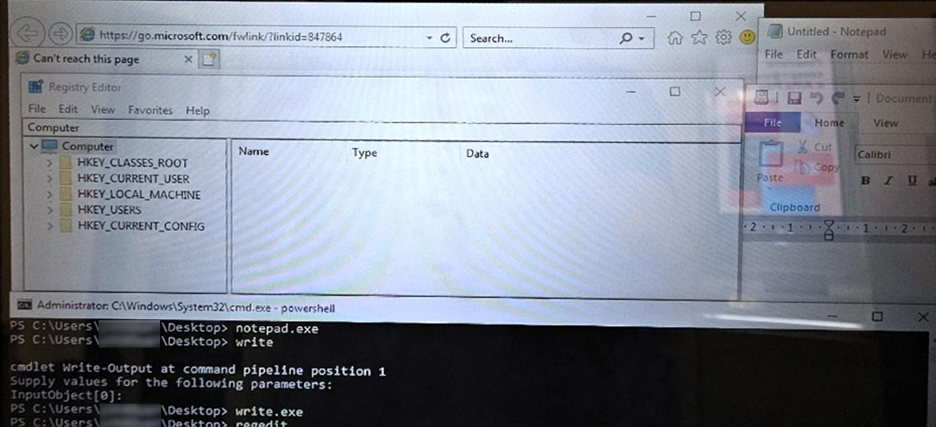

Sometimes, launching Windows Explorer from its default location can also be blocked. In this case, we can return to the example of accessing Explorer using Internet Explorer. Furthermore, the browser allows the necessary actions to be performed without using Explorer: researchers described a method for interacting with the file system using ActiveX technology. The specialists first gained access to the browser and then executed JavaScript code in the developer console (using it to copy the powershell.exe file to a new directory and then launch it). The Scripting.FileSystemObject and WScript.Shell objects were used to access the Windows file system and launch the executable file, respectively.

This example demonstrates that blocking software launches using a blacklist with default paths is inherently insecure, as a way to bypass any subsequent blocking will be found. If File Explorer and the browser are simultaneously blocked from launching using their default paths on a device, access to the browser can be gained by accessing Help in any application that provides this feature.

3.4. Insufficiently effective user security policy configuration (PT‑ATM-003)

It's worth noting that service users can often have excessive privileges, allowing them to perform unauthorized actions on the ATM without bypassing restrictions. A complete lack of restrictions on software launch was found on half of the devices studied.

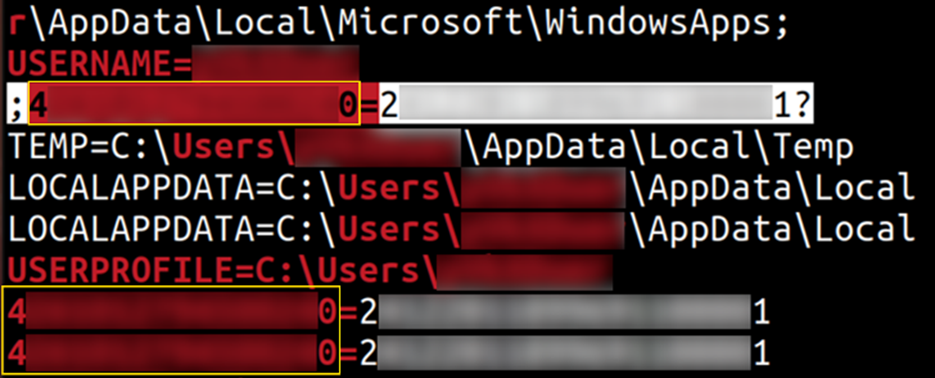

Launching arbitrary software on an ATM

Excessive file access rights of a service user can also pose a threat. For example, an attacker could modify the executable file of a service running with system privileges and gain the ability to execute arbitrary code with maximum privileges.

Recommendations for protection against attacks on control software:

4. Exploiting network configuration flaws

4.1. Changing secure connection parameters (PT‑ATM-415)

On most ATMs, external access to network ports is restricted through the use of a VPN client. VPN solutions not only hinder external interaction with the ATM's network services but also limit the ability to interfere with data exchange between the device and the processing center. Modifying their configuration could be one of the goals of an attacker with access to the operating system.

Sometimes, the VPN connection function is delegated to a separate network device. For example, in such a configuration, traffic encryption may be performed on a switch connected to the system unit's Ethernet port. This allows an attacker with access to the service area to reconnect the cable running from the PC to the switch to their own device (e.g., a laptop), thereby gaining access to unencrypted traffic.

When using a VPN client at the OS level, a hacker can try to exploit previously obtained logical access and disable it, but this often requires administrative privileges. For example, during our research, we were able to render the VPN client inoperable by renaming several drivers and disabling related services.

A rare scenario is possible in which the connection to the processing center is secured using UPO tools rather than a separate VPN solution. For example, researchers examined a UPO in which secure connection parameters were determined by Windows registry keys. One such key is "Protocol," which determines the data transfer protocol used for the connection.

4.2. Exploiting vulnerabilities in ATM network services (PT-ATM-401)

Along with the UPO, ATMs run network services — usually services that allow remote management of the ATM or downloading updates. This network service functionality makes them particularly attractive to hackers, as it allows them to access the ATM's operating system using only network access.

As part of our research, our specialists analyzed the operating principles of one of these network services. The analysis revealed that this application operates using the .NET Remoting protocol and allows remote code execution without authentication. This is accomplished using a method that accepts the path to the executable file on the ATM as a parameter for subsequent execution.

Recommendations for troubleshooting network configuration deficiencies:

5. Substitution of infrastructure elements

5.1. Substitution of the processing center (PT-ATM-421)

After modifying the secure connection configuration, an attacker can interfere with data exchange between the ATM and the processing center. This is done using an emulator that connects to the system unit or network equipment via a patch cable and allows arbitrary responses to ATM requests. The legitimate processing center, however, doesn't even receive requests from the ATM, allowing the desired amounts to be withdrawn without debiting the attacker's card.

One of the weaknesses that allows for theft by spoofing a processing center is the ability to disable necessary checks on behalf of a service user. For example, while investigating a variant of the UPR implementation, researchers discovered the ability to run a utility used to modify its configuration. By modifying security flags, they disabled signature verification of the processing center's messages, allowing the emulator to be used to send commands to the ATM.

5.2. Replacing the monitoring server (PT-ATM-417)

Another example of a network attack involves spoofing a monitoring server used for remote diagnostics and downloading updates. In more than half of the analyzed configurations, the UPO established a connection to the monitoring server without verifying the legitimacy of the connecting node. This allows an attacker to create and use an emulator of the server to remotely execute code on an ATM.

One of the monitoring server implementations examined allowed for uploading ZIP archives to an ATM and remotely executing plugins of a specific format. This could allow a hacker with access to the ATM network to upload malware disguised as plugins with the required extension and initiate their remote execution.

In 2023, researchers from the Synack Red Team identified critical vulnerabilities in ScrutisWeb, a software designed for remote monitoring and management of ATMs. Four vulnerabilities allowed any external attacker to access the web administration interface, enabling a range of actions on ATMs, including remote reboots, file uploads, and device configuration changes.

It's worth noting that patching UPR vulnerabilities can take quite a long time due to its narrow specialization. When addressing UPR vulnerabilities, it's best to implement mitigating measures without waiting for patches: for example, using a VPN client makes network attacks more difficult, and a properly configured firewall will protect ports used by network services.

Recommendations for protection against substitution of infrastructure elements:

Bypassing new authentication methods

ATMs offering biometric authentication are becoming increasingly popular, using facial, fingerprint, and even vein recognition technologies. While card data theft using skimmers was once common, the goal is now to collect and subsequently use biometric data. The problem is compounded by the fact that, unlike bank card information, which can be reissued if compromised, if biometric data is leaked (for example, as a result of a hack into the banking infrastructure), the user cannot change the inherent physical characteristics.

ATMs with facial recognition (left) and finger vein recognition (right)

(sources: CaixaBank, The Guardian)

Additional risks are associated with vulnerabilities in the biometric systems themselves.

There have been cases where facial recognition systems have been bypassed using a photograph or a specially made mask: this method was used by Bkav researchers in 2017 to bypass Face ID technology. Such vulnerabilities are especially dangerous given that biometric authentication replaces PIN entry in some ATMs. For example, in 2020, the Spanish bank CaixaBank introduced ATMs that do not require PIN verification upon successful facial recognition.

An ATM with a QR code-based cash withdrawal function (source: BUSINESS)

ATMs also serve as a cash-out tool in attacks using modified NFCGate software, which have been reported in Russia since October 2024. The final stage of these attacks involves intercepting and retransmitting NFC traffic between the user's card and their device to the attacker's smartphone. The attacker, standing near the ATM, taps their device on the contactless reader and withdraws money from the victim's account. According to data for the first quarter of 2025, damages from such attacks have already exceeded 432 million rubles.

One example is an incident in Thailand recorded in late 2016: attackers, having gained access to a bank's corporate network, compromised a server used to deliver updates and, through it, downloaded malware to several ATMs. That same year, a similar attack in Taiwan resulted in the theft of approximately 80 million New Taiwan dollars (approximately US$2.5 million). The attackers also used access to the bank's network to deliver malware, which enabled remote control of ATMs via Telnet.

Both incidents highlight how vulnerabilities in a bank's network infrastructure can provide an entry point for remote attacks on the ATM network, which attract less attention than attacks that require physical access to the device.

Crypto ATMs (cryptomats) of various designs (sources: DeCenter, Infovend, Hash Telegraph)

The crypto ATM scam is very similar to previously described QR code attacks targeting regular ATMs, but with a key difference: the victim doesn't provide the scammer with the code. Instead, the attacker sends them a pre-generated QR code containing a crypto wallet address and, under the pretext of an urgent need — for example, transferring funds to a secure account — persuades them to deposit cash at the nearest crypto ATM. The deposited funds are automatically converted to cryptocurrency and transferred to the attacker's wallet. What makes these schemes particularly dangerous is that cryptocurrency transactions are more difficult to track and the stolen funds are more difficult to recover.

Attacks target not only users but also the infrastructure itself: in 2023, hackers exploited a zero-day vulnerability in the GENERAL BYTES cloud service, which manages crypto ATMs. The attackers remotely uploaded a malicious Java application to the ATMs and were able to steal customer data (including usernames and password hashes) and transfer funds from hot wallets to their own accounts. The attack disabled the service, causing losses of approximately $1.5 million in cryptocurrency. That same year, researchers identified critical vulnerabilities in Lamassu crypto ATMs. These vulnerabilities allowed an attacker to withdraw bitcoins from user wallets and, if physically accessed, to trick the banknote validator and initiate a transfer of an amount greater than the actual deposit.

It's also worth remembering that with the advancement of technology, more and more logical attack scenarios will emerge. Modern devices are no longer just cash dispensers; they're full-fledged mini-offices where you can pay for services, transfer money, and repay loans. Using a card is also no longer mandatory with the advent of NFC modules, biometrics, and QR code payment on ATMs: a smartphone or a smile may be enough to get started. This makes logical attacks on ATMs increasingly relevant: cash theft may be replaced by transferring funds to a hacker's account, and the theft of card data will give way to bypassing biometric authentication and attacks on the NFC module.

In this article, we've covered the most common ATM attacks and explored the vulnerabilities that allow attackers to steal money without physical intervention. It's important to emphasize that the likelihood of these attacks being carried out in real-world situations should not be underestimated due to their higher complexity compared to traditional methods of stealing money. Some of the attacks described take no more than 10 minutes to execute, but are significantly more difficult to quickly detect.

The attacks described in this article once again highlight the importance of monitoring system events that may indicate unauthorized access to the ATM operating system. Furthermore, it is essential to promptly update the ATM's software and to work with hardware vendors to obtain updates if firmware flaws are discovered. A comprehensive approach to device security is essential, prioritizing both network and local security, as well as physically restricting access to the ATM's service area, which is used by attackers to connect third-party devices to the built-in computer.

(c) Source

In the second part, we'll tell you how ATMs are hacked without any fuss or fuss.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute instructions or a call to commit illegal acts. Our goal is to highlight existing vulnerabilities that can be exploited by attackers and to provide recommendations for protection. The authors assume no liability for the use of this information.

During ATM security analysis, we identify specific vulnerabilities that enable the attacks described above. Below are statistics from our research, highlighting the most common vulnerabilities that lead to cash withdrawals.

The vulnerabilities discussed below are identified by identifiers like PT-ATM-XXX: they are used in an open collection of logical attacks on ATMs prepared by our specialists. The collection contains detailed recommendations for remediating vulnerabilities and descriptions of tests for identifying them, making it useful for both ATM security engineers and security analysts. It can be accessed on GitHub and is available in four languages.

1. Attacks with external control of the dispenser (black box)

All ATM configurations analyzed contained vulnerabilities in the dispenser firmware that could allow for a black-box attack. These attacks are so named because the attacker uses an external device (a kind of black box) to directly control the dispenser. To carry out the attack, access to the ATM's service area, which houses the dispenser's connection to the system unit (hereinafter referred to as the PC), is required. By connecting the appropriate cable to their own device instead of the PC, the hacker can send control commands directly to the dispenser — unless the firmware has sufficiently protected.

Most of the vulnerabilities that allow black box attacks to be carried out are related to flaws in the dispenser's built-in encryption, but there are also other problems.

1.1. Weak encryption algorithm and other shortcomings in the implementation of cryptographic algorithms (PT-ATM-204)

Among the weaknesses associated with encryption of traffic between the PC and the dispenser, the most frequently identified was the use of a weak encryption algorithm: an attacker can exploit known vulnerabilities in the algorithms to reconstruct portions of the protected traffic and extract sensitive information from it. Other weaknesses associated with traffic encryption may include the use of an imperfect random number generation mechanism, the use of hard-coded encryption keys, and other issues requiring an attacker to examine the firmware source code.

1.2. Predictable Authentication Data (PT‑ATM-203)

Another common flaw in dispenser firmware is the use of predictable authentication data, which is performed before information exchange between the PC and the dispenser begins. The purpose of authentication is to verify the authenticity of the source of control traffic arriving at the dispenser. This is done using information that allows the ATM PC to be unambiguously identified as genuine. Authentication data can be static values generated based on the characteristics of the PC or devices connected to it. This allows an attacker with access to the service area to reproduce the required values by analyzing the PC configuration.

Furthermore, authentication data is often present during unencrypted data exchange, making it possible to extract it from USB traffic between the PC and the dispenser by eavesdropping.

1.3. Other vulnerabilities in the dispenser software (PT‑ATM-206)

One of the common issues associated with dispenser firmware is an insecure update delivery and authentication mechanism. In most of the configurations studied, these mechanisms were found to be unreliable — an attacker could inject arbitrary control code into them. Loading such an update into the firmware could lead to both the payment of funds and the disabling of built-in security mechanisms. For example, in some configurations studied, this allowed the signature checks of commands transmitted to the dispenser to be disabled.

Another way to bypass built-in firmware security mechanisms is through buffer overflow. By sending a specially crafted data packet to the dispenser firmware that exceeds the maximum allowed size, an attacker can overwrite the function's stack with their own values.

Recommendations for protection against black box attacks:

- Use strong encryption algorithms for data transfer, such as AES in an authenticated mode (such as GCM or CCM).

- Use reliable mechanisms for authentication, storage, and transmission of passwords between the OS and the dispenser. For example, modern XFS platforms support physical authentication, which ensures that key transfer is only possible with confirmed access to the safe.

- Use secure encryption key generation mechanisms, avoid hard-coded secrets, and avoid using predictable initialization values for the pseudo-random number generator.

- Implement a mechanism for verifying firmware update files. For example, asymmetric cryptographic algorithms could be used for this: a public key is stored on the device, and the update file contains a signature that is verified during the update process. Each firmware update must be signed by the developer.

- Strictly validate the length and format of incoming requests to the dispenser to reduce the likelihood of binary vulnerabilities. Additionally, buffer overflow protection mechanisms should be used.

- Consider using hardware protection against connection to the dispenser's data bus (such as ATM Keeper, Cerber Lock, or ZUB-R). These devices are located in the ATM's secure area, protected from intruders. Unexpected disconnection of the dispenser from the PC, as well as an unplanned reboot of the ATM, should be considered a potential intrusion and trigger an alarm.

2. Gaining access to the ATM operating system (bypassing kiosk mode)

Before we move on to the following attacks, it's important to discuss the methods for gaining access to the ATM operating system. Unless we're talking about black-box attacks, which require a direct connection to the equipment, this step is essential: the average user is unable to fully interact with the ATM and is limited to the interface offered by the kiosk app. Below, we describe vulnerabilities that allow a hacker to bypass kiosk mode and execute operating system commands on the ATM while only having access to the service area.

2.1. No hard drive encryption (PT‑ATM-231)

The lack of hard drive encryption stands out among the weaknesses open to an attacker with access only to the service area. This is because not only is this flaw one of the most common and can be exploited to gain initial access to the OS, but it also allows for the simplest possible theft of funds, which takes no more than 10 minutes.

A simple example of gaining access to the operating system: while examining the contents of an unencrypted hard drive, specialists discovered a BAT file that was executed after the system fully boots up when the ATM was turned on. The line "start cmd.exe" was added to the file, causing the command line interpreter to launch after the ATM reboot. This allowed the attacker to execute operating system commands.

Modifying the BAT file after connecting a hard drive

Launching a command line interpreter as a result of running a script

However, the capabilities of direct access to a hard drive are not limited to this brief example. The high risk of this flaw stems from the fact that, having gained access to the hard drive, a hacker can both install malware on it and modify configuration files to bypass security measures.

Furthermore, access to a hard drive can be an intermediate step in more complex cash theft scenarios. For example, exploiting vulnerabilities in an ATM's software requires knowledge of its operating principles. Obtaining the source code of the software is difficult for an external attacker; studying the executable files using a specialized decompiler may be the most accessible option. The lack of hard drive encryption allows a hacker to copy the software's executable files to a workstation for further study in a more secure environment.

Although the lack of hard drive encryption is a dangerous flaw, its statistics have not improved for several years. Using encryption could not only prevent the simplest method of stealing money but also complicate other attacks that exploit UPR vulnerabilities and bypass security measures.

2.2. Insufficient control of USB device connections (PT‑ATM-004) and insecure configuration of the key whitelist (PT‑ATM-001)

While connecting USB drives to ATMs is often restricted (for example, on some devices, this action is only available to administrators), connecting third-party USB keyboards is generally not prohibited. It's worth noting upfront that this also means connecting other devices recognized by the computer as belonging to the USB HID class (such as the compact Rubber Ducky and Flipper Zero).

One of the drawbacks directly related to connecting a keyboard to an ATM is the ability to exit kiosk mode using keyboard shortcuts. Insufficient restrictions on the most common shortcuts allow access to applications that should not be available to the user during normal ATM operation. For example, a default browser (such as Internet Explorer or Edge) can be used to open Windows Explorer and then launch a command prompt.

2.3. Direct Memory Access (PT‑ATM-232)

As previously mentioned, devices can be connected to the ATM system unit using USB, Ethernet, PCI, and COM interfaces. If the ATM motherboard has a free PCI slot, an attacker can attempt a direct memory access (DMA) attack.

The attack utilizes a DMA card installed in the ATM slot (for example, one based on PCILeech software or a similar tool) to directly access the device's memory, bypassing the operating system's protection mechanisms. This allows data to be read from memory, including payment information transmitted to the ATM, and arbitrary code to be injected directly into memory. Essentially, a DMA attack allows an attacker to execute OS commands with kernel privileges. Thus, a DMA attack allows privileged access to the ATM's operating system, opening up even more opportunities for unauthorized actions.

As an example, the image below shows a RAM dump containing a bank account number (PAN) - a 16-digit sequence highlighted in yellow.

A dump of the attacked device's RAM, obtained using PCILeech

Recommendations for preventing access to the OS:

- Use hardware or software hard drive encryption. It's important to ensure secure storage of the encryption key, such as using a hardware TPM (Trusted Platform Module). Storing the key on an unencrypted drive is strongly discouraged.

- Restrict USB devices connected during normal ATM operation. This can be done using Windows policies and/or Device Control security features.

- Limit the use of common key combinations that are not required for normal ATM operation (such as Win+F1, Alt+F4, Ctrl+Win+Enter, Alt+Tab, Ctrl+Alt+F12). Additionally, limit the use of touchscreen gestures if relevant to the specific ATM configuration.

- Enable DMA attack protection. For example, the following methods are available for Windows:

- Open Windows security settings (Windows Settings > Privacy & security > Windows Security) and go to the Core Isolation settings (Device security > Core isolation details). Set the Memory integrity setting to On and ensure Memory Access Protection is listed among the available security features.

- Set the Kernel DMA Protection parameter to On using the System Information application (msinfo32.exe).

- Monitor and analyze events outside of scheduled maintenance hours (maintenance or collection) that may indicate unauthorized access to the ATM operating system:

- opening of the ATM case or unplanned transition to service mode;

- ATM power failure followed by power-on, despite the presence of a stable power source;

- OS reboot or user logout without any recorded reasons or errors in the ATM activity logs, as well as editing the activity logs on the hard drive.

3. Attacks on vulnerabilities in control software

3.1. Insecure implementation of file integrity control of control software (PT‑ATM-417)

By bypassing kiosk mode, a hacker can perform actions on behalf of a service user (this account is used by the ATM to perform functions, such as launching a banking application in kiosk mode). The attacker can attempt to dispense cash using malicious tools that target the ATM's ATM.

As mentioned earlier, the UPO controls ATM peripherals using the CEN/XFS standard. The open nature of this standard not only facilitates the spread of generic malware but also poses a threat to the UPO, which has issues with integrity control of executable and configuration files.

During our research, we found insecure implementation of UPO file integrity monitoring in most of the configurations examined. This flaw can manifest itself in various ways — for example, if the UPO:

- There is a built-in option to disable the application file checking;

- The function used to calculate file hashes can be modified. If the hash is calculated incorrectly, the integrity check may fail, allowing an attacker to modify the files.

- The integrity check is performed only once when the application is launched and applies to files with extensions from a specified list. If an attacker uses a payload with an extension not included in the list, the integrity check will pass.

3.2. Insufficient protection against reflection attacks (PT‑ATM-417)

The UPR analyzed by the specialists was written in just-in-time (JIT) compiled languages. Some of these, including C#, have reflection capabilities: a program can analyze its structure at runtime, dynamically invoke methods, modify object state, and access type metadata. Reflection can be exploited by hackers: insufficient integrity checking of executable files allows for an attack, to which most of the analyzed configurations were vulnerable.

It's worth noting that performing a reflection attack requires a high level of skill from the attacker: they must write an exploit for a specific implementation of the UPR. Before developing an exploit, it's essential to understand the UPR's operating principles. If the application's source code is unavailable, specialized decompilers and debuggers, such as dnSpy (for C#), are used.

3.3. Bypassing third-party software launch controls (PT-ATM-019)

Another potential obstacle may be software restrictions — for example, prohibiting the use of command-line interpreters, which are necessary for interacting with malware. On Windows-based ATMs, solutions such as AppLocker or software restriction policies (SRPs) are often used for blocking. Third-party Application Control solutions are also possible.

Blocking the launch of certain software (for example, the command line interpreters cmd.exe and powershell.exe) is often accomplished using a blacklist, which includes standard paths to executable files. The first obvious drawback of this method is the ability to launch third-party software not on the blacklist, including malware. Another drawback is that bypassing the blocking requires launching the executable file from an alternative location. In the simplest case, this can be accomplished using Windows Explorer.

As a demonstration, we used AppLocker to block PowerShell from running from the C:\Windows\System32\Windows\PowerShell\v1.0 directory. To bypass the block, the specialists copied the powershell.exe executable file to the service user's desktop and then ran the file from the new location.

Block PowerShell from running according to an AppLocker rule

Launching PowerShell from a non-standard location

Sometimes, launching Windows Explorer from its default location can also be blocked. In this case, we can return to the example of accessing Explorer using Internet Explorer. Furthermore, the browser allows the necessary actions to be performed without using Explorer: researchers described a method for interacting with the file system using ActiveX technology. The specialists first gained access to the browser and then executed JavaScript code in the developer console (using it to copy the powershell.exe file to a new directory and then launch it). The Scripting.FileSystemObject and WScript.Shell objects were used to access the Windows file system and launch the executable file, respectively.

This example demonstrates that blocking software launches using a blacklist with default paths is inherently insecure, as a way to bypass any subsequent blocking will be found. If File Explorer and the browser are simultaneously blocked from launching using their default paths on a device, access to the browser can be gained by accessing Help in any application that provides this feature.

3.4. Insufficiently effective user security policy configuration (PT‑ATM-003)

It's worth noting that service users can often have excessive privileges, allowing them to perform unauthorized actions on the ATM without bypassing restrictions. A complete lack of restrictions on software launch was found on half of the devices studied.

Launching arbitrary software on an ATM

Excessive file access rights of a service user can also pose a threat. For example, an attacker could modify the executable file of a service running with system privileges and gain the ability to execute arbitrary code with maximum privileges.

Recommendations for protection against attacks on control software:

- Implement UPR protection measures against attacks that utilize reflection mechanisms (the specific implementation of such measures will depend on the application's development language). To make it more difficult for an attacker to analyze the application, source code obfuscation techniques should be used.

- Limit the privileges of the service user, based on the minimum set of rights necessary for the software to function.

- Use more flexible policies in application launch controls, such as blocking by hash or publisher.

- Consider setting up application launch controls based on a whitelist (allowing only those utilities required for the ATM to function properly) to prevent third-party software from running on the ATM.

- Regularly update the software used on your ATM.

4. Exploiting network configuration flaws

4.1. Changing secure connection parameters (PT‑ATM-415)

On most ATMs, external access to network ports is restricted through the use of a VPN client. VPN solutions not only hinder external interaction with the ATM's network services but also limit the ability to interfere with data exchange between the device and the processing center. Modifying their configuration could be one of the goals of an attacker with access to the operating system.

Sometimes, the VPN connection function is delegated to a separate network device. For example, in such a configuration, traffic encryption may be performed on a switch connected to the system unit's Ethernet port. This allows an attacker with access to the service area to reconnect the cable running from the PC to the switch to their own device (e.g., a laptop), thereby gaining access to unencrypted traffic.

When using a VPN client at the OS level, a hacker can try to exploit previously obtained logical access and disable it, but this often requires administrative privileges. For example, during our research, we were able to render the VPN client inoperable by renaming several drivers and disabling related services.

A rare scenario is possible in which the connection to the processing center is secured using UPO tools rather than a separate VPN solution. For example, researchers examined a UPO in which secure connection parameters were determined by Windows registry keys. One such key is "Protocol," which determines the data transfer protocol used for the connection.

4.2. Exploiting vulnerabilities in ATM network services (PT-ATM-401)

Along with the UPO, ATMs run network services — usually services that allow remote management of the ATM or downloading updates. This network service functionality makes them particularly attractive to hackers, as it allows them to access the ATM's operating system using only network access.

As part of our research, our specialists analyzed the operating principles of one of these network services. The analysis revealed that this application operates using the .NET Remoting protocol and allows remote code execution without authentication. This is accomplished using a method that accepts the path to the executable file on the ATM as a parameter for subsequent execution.

Recommendations for troubleshooting network configuration deficiencies:

- Restrict access to network ports by allowing connections only for trusted processes that require them in normal operation.

- To protect interactions with the processing center, use separate VPN solutions (not included in the UPO) that are resistant to emergency situations, such as:

- loading the ATM in safe mode;

- unplanned device shutdown;

- disconnecting or reconnecting network equipment (if encryption is performed by a separate device);

- connection of unauthorized network equipment or loss of connection with the target device while the VPN client is active.

- Limit service user privileges based on the minimum set of rights necessary for operation. For example, for Windows systems, it would be appropriate to impose the following restrictions:

- prohibit the launch of standard utilities for working with the certificate store;

- Leave read-only permission for critical registry branches - the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software subbranches related to the ATM UPO, as well as the HKEY_CURRENT_USERS\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\SystemCertificates branch.

5. Substitution of infrastructure elements

5.1. Substitution of the processing center (PT-ATM-421)

After modifying the secure connection configuration, an attacker can interfere with data exchange between the ATM and the processing center. This is done using an emulator that connects to the system unit or network equipment via a patch cable and allows arbitrary responses to ATM requests. The legitimate processing center, however, doesn't even receive requests from the ATM, allowing the desired amounts to be withdrawn without debiting the attacker's card.

One of the weaknesses that allows for theft by spoofing a processing center is the ability to disable necessary checks on behalf of a service user. For example, while investigating a variant of the UPR implementation, researchers discovered the ability to run a utility used to modify its configuration. By modifying security flags, they disabled signature verification of the processing center's messages, allowing the emulator to be used to send commands to the ATM.

5.2. Replacing the monitoring server (PT-ATM-417)

Another example of a network attack involves spoofing a monitoring server used for remote diagnostics and downloading updates. In more than half of the analyzed configurations, the UPO established a connection to the monitoring server without verifying the legitimacy of the connecting node. This allows an attacker to create and use an emulator of the server to remotely execute code on an ATM.

One of the monitoring server implementations examined allowed for uploading ZIP archives to an ATM and remotely executing plugins of a specific format. This could allow a hacker with access to the ATM network to upload malware disguised as plugins with the required extension and initiate their remote execution.

In 2023, researchers from the Synack Red Team identified critical vulnerabilities in ScrutisWeb, a software designed for remote monitoring and management of ATMs. Four vulnerabilities allowed any external attacker to access the web administration interface, enabling a range of actions on ATMs, including remote reboots, file uploads, and device configuration changes.

It's worth noting that patching UPR vulnerabilities can take quite a long time due to its narrow specialization. When addressing UPR vulnerabilities, it's best to implement mitigating measures without waiting for patches: for example, using a VPN client makes network attacks more difficult, and a properly configured firewall will protect ports used by network services.

Recommendations for protection against substitution of infrastructure elements:

- Implement integrity control of requests to the processing center to prevent the possibility of their modification, for example, by adding an impersonation insert to the request or using a MAC (Message Authentication Code).

- Perform additional verification of data returned by the processing center. Disabling security checks performed on the ATM side should not be possible either from the processing center or locally on behalf of the service user.

- Implement authentication and authorization mechanisms for ATM network services:

- Requests to ATM network services must be made using a digital signature, especially for services whose standard functionality includes writing and executing files;

- Remote diagnostics and installation of updates on the ATM should be available only from a specially designated installation server (jump server), access to which is limited to a limited number of employees.

The Future of ATM Attacks

The attacks discussed here relate to potential ATM hacks occurring here and now. However, technological advancements are not bypassing these devices, resulting in them acquiring new features and the emergence of additional attack vectors. In this section, we will attempt to make some predictions about what ATM attacks will look like in the near future.Bypassing new authentication methods

ATMs offering biometric authentication are becoming increasingly popular, using facial, fingerprint, and even vein recognition technologies. While card data theft using skimmers was once common, the goal is now to collect and subsequently use biometric data. The problem is compounded by the fact that, unlike bank card information, which can be reissued if compromised, if biometric data is leaked (for example, as a result of a hack into the banking infrastructure), the user cannot change the inherent physical characteristics.

ATMs with facial recognition (left) and finger vein recognition (right)

(sources: CaixaBank, The Guardian)

Additional risks are associated with vulnerabilities in the biometric systems themselves.

There have been cases where facial recognition systems have been bypassed using a photograph or a specially made mask: this method was used by Bkav researchers in 2017 to bypass Face ID technology. Such vulnerabilities are especially dangerous given that biometric authentication replaces PIN entry in some ATMs. For example, in 2020, the Spanish bank CaixaBank introduced ATMs that do not require PIN verification upon successful facial recognition.

ATM as a link in fraudulent schemes

With advances in technology, ATMs are increasingly becoming less of a direct target and more of an intermediary in fraudulent schemes. One such example is the introduction of card-free withdrawals on modern ATMs, using a QR code. In some cases, users simply need to generate a QR code in a bank's mobile app and scan it at the ATM. Fraudsters have already exploited this innovation, adapting a standard social engineering scheme: victims are informed of a fictitious unauthorized transaction and persuaded to send a QR code to cancel it. In reality, the scammers scan the resulting QR code at the ATM and withdraw money from the victim's account.

An ATM with a QR code-based cash withdrawal function (source: BUSINESS)

ATMs also serve as a cash-out tool in attacks using modified NFCGate software, which have been reported in Russia since October 2024. The final stage of these attacks involves intercepting and retransmitting NFC traffic between the user's card and their device to the attacker's smartphone. The attacker, standing near the ATM, taps their device on the contactless reader and withdraws money from the victim's account. According to data for the first quarter of 2025, damages from such attacks have already exceeded 432 million rubles.

Network attacks through banking infrastructure

Back in 2017, Trend Micro, in collaboration with Europol, noted a shift in attack vectors — from attacks requiring physical access to the service area to accessing ATMs from within the bank's network. With insufficient network segmentation, compromising a bank's internal infrastructure allows attackers to develop attacks on connected ATMs.One example is an incident in Thailand recorded in late 2016: attackers, having gained access to a bank's corporate network, compromised a server used to deliver updates and, through it, downloaded malware to several ATMs. That same year, a similar attack in Taiwan resulted in the theft of approximately 80 million New Taiwan dollars (approximately US$2.5 million). The attackers also used access to the bank's network to deliver malware, which enabled remote control of ATMs via Telnet.

Both incidents highlight how vulnerabilities in a bank's network infrastructure can provide an entry point for remote attacks on the ATM network, which attract less attention than attacks that require physical access to the device.

Attacks on cryptocurrency ATMs

As interest in cryptocurrencies grows, the number of crypto ATMs continues to grow : by 2024, their number increased by 3%, reaching 37,700 devices worldwide. Crypto ATMs (or crypto ATMs) allow both the purchase and sale of cryptocurrency. To start using a terminal, simply enter your wallet address by scanning its QR code from your mobile device.

Crypto ATMs (cryptomats) of various designs (sources: DeCenter, Infovend, Hash Telegraph)

The crypto ATM scam is very similar to previously described QR code attacks targeting regular ATMs, but with a key difference: the victim doesn't provide the scammer with the code. Instead, the attacker sends them a pre-generated QR code containing a crypto wallet address and, under the pretext of an urgent need — for example, transferring funds to a secure account — persuades them to deposit cash at the nearest crypto ATM. The deposited funds are automatically converted to cryptocurrency and transferred to the attacker's wallet. What makes these schemes particularly dangerous is that cryptocurrency transactions are more difficult to track and the stolen funds are more difficult to recover.

Attacks target not only users but also the infrastructure itself: in 2023, hackers exploited a zero-day vulnerability in the GENERAL BYTES cloud service, which manages crypto ATMs. The attackers remotely uploaded a malicious Java application to the ATMs and were able to steal customer data (including usernames and password hashes) and transfer funds from hot wallets to their own accounts. The attack disabled the service, causing losses of approximately $1.5 million in cryptocurrency. That same year, researchers identified critical vulnerabilities in Lamassu crypto ATMs. These vulnerabilities allowed an attacker to withdraw bitcoins from user wallets and, if physically accessed, to trick the banknote validator and initiate a transfer of an amount greater than the actual deposit.

Conclusion

The rise of new ATM malware implementations and the lower barrier to entry for attackers have made logical attacks on these devices more relevant than ever. While attackers previously focused on stealing ATM users' card data using techniques that didn't interfere with the device's logic, today a single logical attack can yield a large sum of cash. Ready-made solutions offered on shadow marketplaces are accessible to attackers with minimal tools and low skill levels. However, the focus of ATM security strategies remains on physical security and network security. As a result, ATMs remain vulnerable to simple yet effective theft scenarios.It's also worth remembering that with the advancement of technology, more and more logical attack scenarios will emerge. Modern devices are no longer just cash dispensers; they're full-fledged mini-offices where you can pay for services, transfer money, and repay loans. Using a card is also no longer mandatory with the advent of NFC modules, biometrics, and QR code payment on ATMs: a smartphone or a smile may be enough to get started. This makes logical attacks on ATMs increasingly relevant: cash theft may be replaced by transferring funds to a hacker's account, and the theft of card data will give way to bypassing biometric authentication and attacks on the NFC module.

In this article, we've covered the most common ATM attacks and explored the vulnerabilities that allow attackers to steal money without physical intervention. It's important to emphasize that the likelihood of these attacks being carried out in real-world situations should not be underestimated due to their higher complexity compared to traditional methods of stealing money. Some of the attacks described take no more than 10 minutes to execute, but are significantly more difficult to quickly detect.

The attacks described in this article once again highlight the importance of monitoring system events that may indicate unauthorized access to the ATM operating system. Furthermore, it is essential to promptly update the ATM's software and to work with hardware vendors to obtain updates if firmware flaws are discovered. A comprehensive approach to device security is essential, prioritizing both network and local security, as well as physically restricting access to the ATM's service area, which is used by attackers to connect third-party devices to the built-in computer.

(c) Source