Brother

Professional

- Messages

- 2,590

- Reaction score

- 533

- Points

- 113

A month ago, a Forbes journalist demonstrated the (in) reliability of biometric security in consumer-grade devices. For the test, he ordered a plaster 3D copy of his head, after which he tried to use this model to unlock smartphones of five models: LG G7 ThinQ, Samsung S9, Samsung Note 8, OnePlus 6 and iPhone X.

A plaster copy was sufficient to unlock four out of five models tested. Although the iPhone did not succumb to the trick (it scans in the infrared range), the experiment showed that face recognition is not the most reliable method of protecting confidential information. In general, like many other biometrics methods.

In a comment, representatives of the "affected" companies said that facial recognition makes phone unlocking "convenient", but a fingerprint or iris scanner is recommended for "the highest level of biometric authentication".

The experiment also showed that for a real hack, a couple of photographs of the victim are not enough, because they will not allow you to create a full 3D copy of the skull. Making a workable prototype requires multiple angles and good lighting. On the other hand, thanks to social networks, it is now possible to get a large amount of such photo and video material, and the resolution of cameras is increasing every year.

Other methods of biometric protection are also not devoid of vulnerabilities.

Fingerprints

Fingerprint scanning systems became widespread in the 90s - and were immediately attacked.

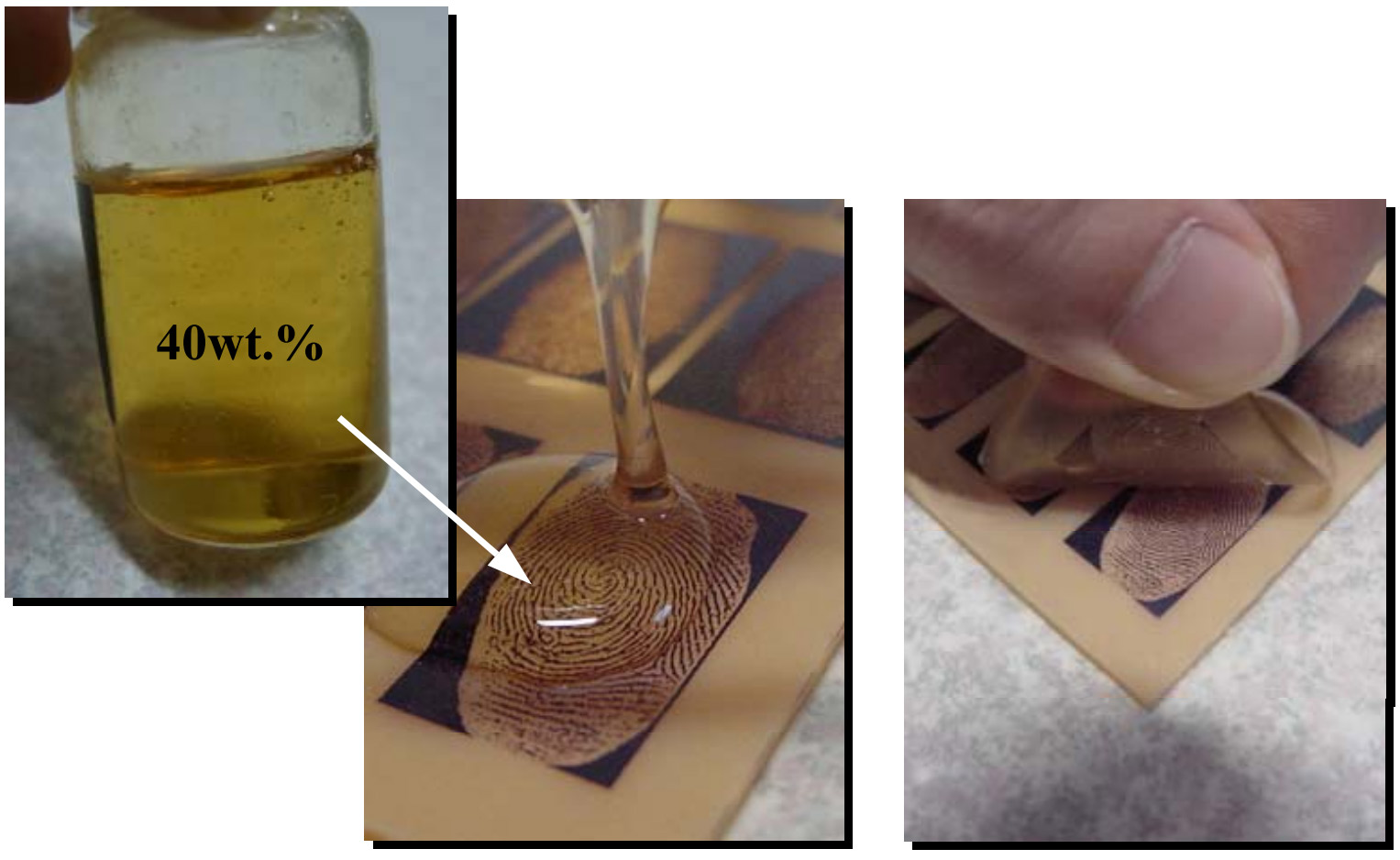

In the early 2000s, hackers perfected the mechanism for making artificial silicone copies from an existing pattern. If you stick a thin film on your own finger, you can fool almost any system, even with other sensors, that checks the temperature of the human body and makes sure that the finger of a living person is attached to the scanner, and not a printout.

The classic guide to making artificial prints is considered to be Tsutomu Matsumoto's 2002 guide . It explains in detail how to process a victim's fingerprint using graphite powder or cyanoacrylate vapor (superglue), how to process the photo before making the mold, and finally, make a convex mask using gelatin, latex milk or wood glue.

Production of a gelatinous film with a fingerprint pattern using a contour mold with a fingerprint. Source: Tsutomu Matsumoto's Instruction

The biggest challenge in this procedure is copying a real fingerprint. The highest quality prints are said to remain on glass surfaces and doorknobs. But in our time, another way has appeared: the resolution of some photographs allows you to restore a drawing directly from a photograph.

In 2017, a project was reported by researchers from the National Institute of Informatics of Japan. They proved it was possible to recreate a fingerprint pattern from photographs taken with a digital camera from a distance of three meters. Back in 2014, at the hacker conference Chaos Communication Congress, they showed the fingerprints of the German Defense Minister, recreated from official high-resolution photos from open sources.

Other biometrics

In addition to fingerprint scanning and face recognition, other methods of biometric protection are not yet widely used in modern smartphones, although there is a theoretical possibility. Some of these methods have been experimentally tested, others have been commercialized in a variety of applications, including retinal scanning, voice verification, and palm vein pattern verification.But all biometric security methods have one fundamental vulnerability: unlike a password, their biometric characteristics are almost impossible to replace. If your fingerprints are leaked to the public, you won't change them. It can be said to be a lifelong vulnerability.

“As the camera resolution gets higher, it becomes possible to view smaller objects such as a fingerprint or iris. [...] Once you share them on social media, you can say goodbye. Unlike a password, you cannot change your fingers. So this is information that you have to protect. "- Isao Echizen, Professor at the National Institute of Informatics of Japan

No biometric security method gives a 100% guarantee. When testing each system, the following parameters are indicated:

- accuracy (several types);

- the percentage of false positives (false alarm);

- the percentage of false negatives (event skipping).

These parameters depend on each other. Due to the system settings, you can, for example, increase the recognition accuracy up to 100% - but then the number of false positives will also increase. Conversely, you can reduce the number of false positives to zero - but then accuracy will suffer.

Obviously, now many protection methods are easily hacked for the reason that manufacturers primarily think about usability, not reliability. In other words, they prioritize the minimum number of false positives.

The economy of hacking

As in economics, there is also a concept of economic expediency in information security. Let there be no one hundred percent protection. But safeguards correlate with the value of the information itself. In general, the principle is something like that the cost of the hacking effort for a hacker should exceed the value to him of the information he wants to obtain. The larger the ratio, the more durable the protection.If we take the example of a plaster copy of a head to deceive a system like Face ID, then it cost a Forbes journalist about $ 380. Accordingly, it makes sense to use this technology to protect information costing less than $ 380. This is an excellent security technology for protecting penny information, but a lousy technology for corporate trade secrets, so everything is relative. It turns out that in each specific case it is necessary to assess the minimum permissible degree of protection. For example, face recognition combined with a password - like two-factor authentication - already increases the level of protection by an order of magnitude, compared to only face recognition or just one password.

In general, any protection can be hacked. The question is the cost of the effort.