In the previous part, we talked about the history of the magnetic stripe payment card. In this article we will continue our story. But we will now talk about plastic cards with built-in chips and other promising technologies in this area.

The real patent race began when the idea of adapting a different electronic storage medium to a payment card than a piece of tape was born. Such a carrier was already known. It was a so-called integrated circuit based on a tiny crystal of silicon semiconductor, which is now called a chip, a microprocessor, and half a dozen other terms depending on its field of application.

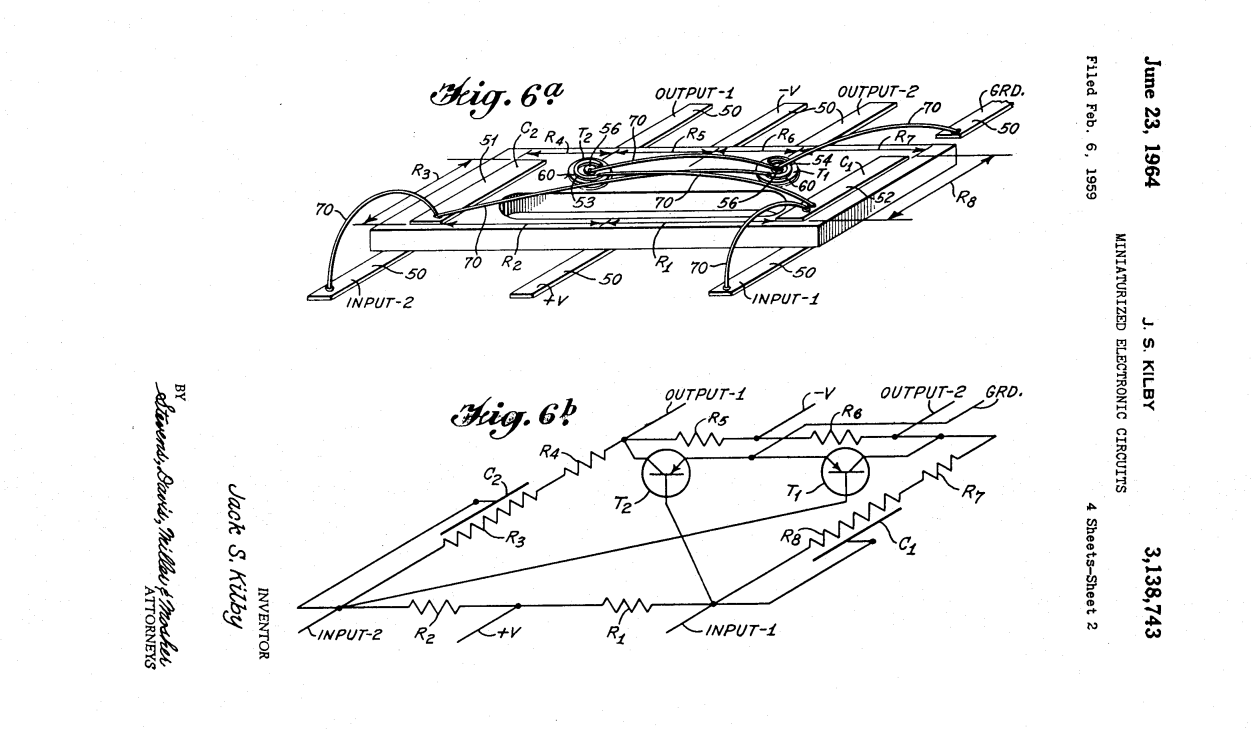

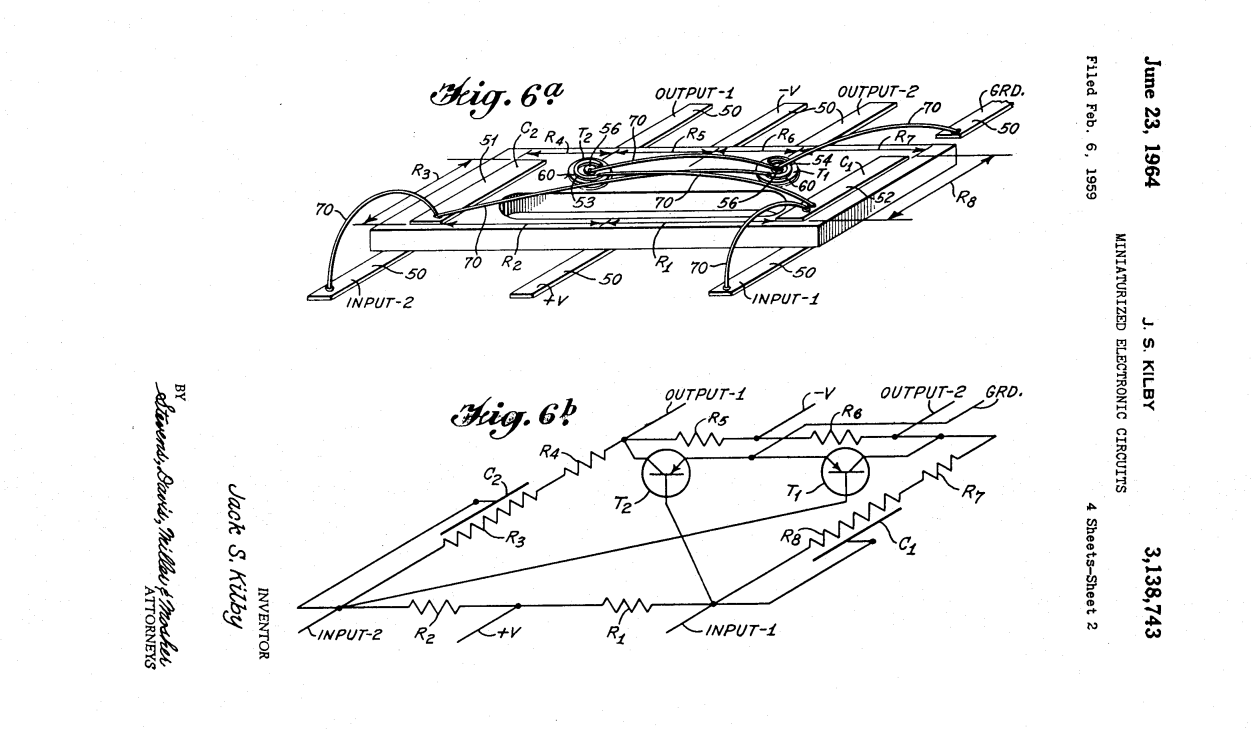

Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments (now the leader in the mobile chip market) filed a patent application for the operating principle of the integrated circuit in 1959, and his patent (US3138743) was approved in 1964. Meanwhile, microprocessors were actively being developed in many countries, including ours, where mass production of semiconductor chips began in 1965.

And the first patent application for the use of a silicon semiconductor in a payment card was filed in 1966 by the head and owner of a small private company DATEGE in Munich, Helmut Gröttrupp (German patent No. 1524695 of 1970 “Recording media with conductive marks, printed circuit boards or elements of semiconductor circuits, for example, credit cards or identity cards” with priority dated December 1966), a very interesting person, by the way, with a difficult fate.

A graduate of the Technical University of Berlin in 1939, Helmut Gröttrupp three years later already headed the rocket radio control department at the Wernher von Braun rocket center in Peenemünde. In 1945, having been captured by the Americans and awaiting transport to the United States, he secretly, through his wife, asked the Soviet command to send him and his family to the Soviet Union. Here he participated in the creation of the first Soviet ballistic missile. In 1953 he returned to Germany and there he no longer returned to rocket science, but became interested in the new field of information technology, where he also succeeded.

In the late 1960s, he filed a total of four patent applications for chip cards with the German Patent and Trademark Office, the last two in 1968 and 1969 for “Active credit cards equipped with a means of personalizing their user with a PIN entry/comparison system.” code" - co-authored with his investor, Hamburg engineer Jürgen Detloff. Later, in addition to German ones, they also received UK (GB1317915 and GB1318850) and US (US3678250) patents for this invention.

And since the early 1970s, there has been a real wave of patent applications for microchip storage media on payment and ID cards. For example, Roland Moreno of France alone filed 47 such patent applications, the first of which, from 1974, included a microchip embedded in his ring. IBM also noted here with a patent from its employee Paul Castrucci from the Vermont branch of the corporation. As engineer Castrucci himself says, for him this invention was a by-product: “In 1966, Bob Henley (Castrucci’s colleague - Ed.) and I rolled up our sleeves and invented semiconductor memory. By Christmas our 16-bit platters were tested, and in 1966 our computer with them was sent to the NSA."

In other words, engineers Castrucci and Henley designed a computer with semiconductor chips for the US National Security Agency. And when the boom in patent applications for microchips for payment cards began, Castrucci filed an application for his own version of a microchip, why not file if there is such an opportunity and relevant developments? As he writes in the “Claims” section of his application: “In addition to standard credit and personal information, security code information can also be entered and stored in the monolithic solid-state memory (chip - Ed.) of the card. To activate the card, you must insert it into the terminal and enter the appropriate security code from the keypad of an autonomous station or into a conventional computer transmission system ... If the code data matches, the card will activate the central data bank and confirm the transaction" (patent US3702464 with priority dated May 4, 1971) .

As the “father” of the magnetic card, Jerome Svigals, recalled, the greatest difficulties for his brainchild, cards with a magnetic stripe, arose in the mid-1980s, when the industrial technology for manufacturing smart cards finally appeared. “In Europe and some other regions outside North America, microchip-based smart cards have almost completely replaced magnetic stripe cards, but in the United States and Canada the latter are still very popular,” he wrote in 2012 and continued with undisguised sadness . “But the end of magnetic stripe cards is just around the corner. Emerging technologies for payments using smartphones and near field communication (NFC) in the radio frequency range are gaining popularity, and will likely eventually completely replace the venerable credit cards, even in North America. And as we stand on the threshold of a new era, the era of high-tech transactions, it is time to sing the praises of those forgotten engineers who were behind the creation of the technology that has been so stunningly successful.”

It is difficult to add anything to this. The only thing is that in our country the first domestic Eurocard/MasterCard with its own logo was issued by Vnesheconombank and solemnly presented by the leadership of the organization to the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Mikhail Gorbachev, who turned it over in his hands, but did not put it in his pocket, but gave it to the guards and ordered take it to the museum. Payment cards reached our people only in the 1990s. First, in 1992, to those citizens who could make a deposit of $15,000 of their hard-earned money on a deposit in the commercial Most Bank, which began issuing VISA credit cards, and by the end of the 1990s, to everyone else.

As for the fact that we are on the threshold of a new era of high-tech transactions, the next step on the magnetic tape-chip-radio chip path may be what, for lack of a proper name, is still called “biotechnology,” meaning the reading of biometric personal data (firstly sequence of fingerprints and iris patterns). Fingerprint (Touch ID) and iris scanners are already built into some models of modern smartphones, so there are no unsolvable problems along the way.

And then it seems that things will come to DNA identification; here, too, there is no fundamental obstacle, so far the enthusiasm of inventors is restrained only by the relatively high cost of PCR (procedures for repeatedly copying DNA sections to an amount suitable for analysis). But as soon as it drops to an acceptable threshold, terminals and ATMs will appear with a receiver of biological fluids, into which you only have to spit to complete a transaction. There is no need to laugh here; at first they also laughed at Mrs. Perry’s iron. But where has he taken us!

The real patent race began when the idea of adapting a different electronic storage medium to a payment card than a piece of tape was born. Such a carrier was already known. It was a so-called integrated circuit based on a tiny crystal of silicon semiconductor, which is now called a chip, a microprocessor, and half a dozen other terms depending on its field of application.

Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments (now the leader in the mobile chip market) filed a patent application for the operating principle of the integrated circuit in 1959, and his patent (US3138743) was approved in 1964. Meanwhile, microprocessors were actively being developed in many countries, including ours, where mass production of semiconductor chips began in 1965.

And the first patent application for the use of a silicon semiconductor in a payment card was filed in 1966 by the head and owner of a small private company DATEGE in Munich, Helmut Gröttrupp (German patent No. 1524695 of 1970 “Recording media with conductive marks, printed circuit boards or elements of semiconductor circuits, for example, credit cards or identity cards” with priority dated December 1966), a very interesting person, by the way, with a difficult fate.

A graduate of the Technical University of Berlin in 1939, Helmut Gröttrupp three years later already headed the rocket radio control department at the Wernher von Braun rocket center in Peenemünde. In 1945, having been captured by the Americans and awaiting transport to the United States, he secretly, through his wife, asked the Soviet command to send him and his family to the Soviet Union. Here he participated in the creation of the first Soviet ballistic missile. In 1953 he returned to Germany and there he no longer returned to rocket science, but became interested in the new field of information technology, where he also succeeded.

In the late 1960s, he filed a total of four patent applications for chip cards with the German Patent and Trademark Office, the last two in 1968 and 1969 for “Active credit cards equipped with a means of personalizing their user with a PIN entry/comparison system.” code" - co-authored with his investor, Hamburg engineer Jürgen Detloff. Later, in addition to German ones, they also received UK (GB1317915 and GB1318850) and US (US3678250) patents for this invention.

And since the early 1970s, there has been a real wave of patent applications for microchip storage media on payment and ID cards. For example, Roland Moreno of France alone filed 47 such patent applications, the first of which, from 1974, included a microchip embedded in his ring. IBM also noted here with a patent from its employee Paul Castrucci from the Vermont branch of the corporation. As engineer Castrucci himself says, for him this invention was a by-product: “In 1966, Bob Henley (Castrucci’s colleague - Ed.) and I rolled up our sleeves and invented semiconductor memory. By Christmas our 16-bit platters were tested, and in 1966 our computer with them was sent to the NSA."

In other words, engineers Castrucci and Henley designed a computer with semiconductor chips for the US National Security Agency. And when the boom in patent applications for microchips for payment cards began, Castrucci filed an application for his own version of a microchip, why not file if there is such an opportunity and relevant developments? As he writes in the “Claims” section of his application: “In addition to standard credit and personal information, security code information can also be entered and stored in the monolithic solid-state memory (chip - Ed.) of the card. To activate the card, you must insert it into the terminal and enter the appropriate security code from the keypad of an autonomous station or into a conventional computer transmission system ... If the code data matches, the card will activate the central data bank and confirm the transaction" (patent US3702464 with priority dated May 4, 1971) .

As the “father” of the magnetic card, Jerome Svigals, recalled, the greatest difficulties for his brainchild, cards with a magnetic stripe, arose in the mid-1980s, when the industrial technology for manufacturing smart cards finally appeared. “In Europe and some other regions outside North America, microchip-based smart cards have almost completely replaced magnetic stripe cards, but in the United States and Canada the latter are still very popular,” he wrote in 2012 and continued with undisguised sadness . “But the end of magnetic stripe cards is just around the corner. Emerging technologies for payments using smartphones and near field communication (NFC) in the radio frequency range are gaining popularity, and will likely eventually completely replace the venerable credit cards, even in North America. And as we stand on the threshold of a new era, the era of high-tech transactions, it is time to sing the praises of those forgotten engineers who were behind the creation of the technology that has been so stunningly successful.”

It is difficult to add anything to this. The only thing is that in our country the first domestic Eurocard/MasterCard with its own logo was issued by Vnesheconombank and solemnly presented by the leadership of the organization to the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Mikhail Gorbachev, who turned it over in his hands, but did not put it in his pocket, but gave it to the guards and ordered take it to the museum. Payment cards reached our people only in the 1990s. First, in 1992, to those citizens who could make a deposit of $15,000 of their hard-earned money on a deposit in the commercial Most Bank, which began issuing VISA credit cards, and by the end of the 1990s, to everyone else.

As for the fact that we are on the threshold of a new era of high-tech transactions, the next step on the magnetic tape-chip-radio chip path may be what, for lack of a proper name, is still called “biotechnology,” meaning the reading of biometric personal data (firstly sequence of fingerprints and iris patterns). Fingerprint (Touch ID) and iris scanners are already built into some models of modern smartphones, so there are no unsolvable problems along the way.

And then it seems that things will come to DNA identification; here, too, there is no fundamental obstacle, so far the enthusiasm of inventors is restrained only by the relatively high cost of PCR (procedures for repeatedly copying DNA sections to an amount suitable for analysis). But as soon as it drops to an acceptable threshold, terminals and ATMs will appear with a receiver of biological fluids, into which you only have to spit to complete a transaction. There is no need to laugh here; at first they also laughed at Mrs. Perry’s iron. But where has he taken us!