Carding Forum

Professional

- Messages

- 2,788

- Reaction score

- 1,323

- Points

- 113

The "holy" bank was repeatedly accused of money laundering and connections with the mafia.

How the Vatican Bank works.

The Vatican Bank, also known as the Institute for Religious Affairs (IOR), is a private financial institution located in the Vatican City State. The bank has been at the center of numerous scandals over the decades. Its leadership has faced allegations of mismanagement, money laundering, fraud, and mafia ties for years. Further in the article, the PaySpace Magazine editorial staff tells how the most closed bank in the world works.

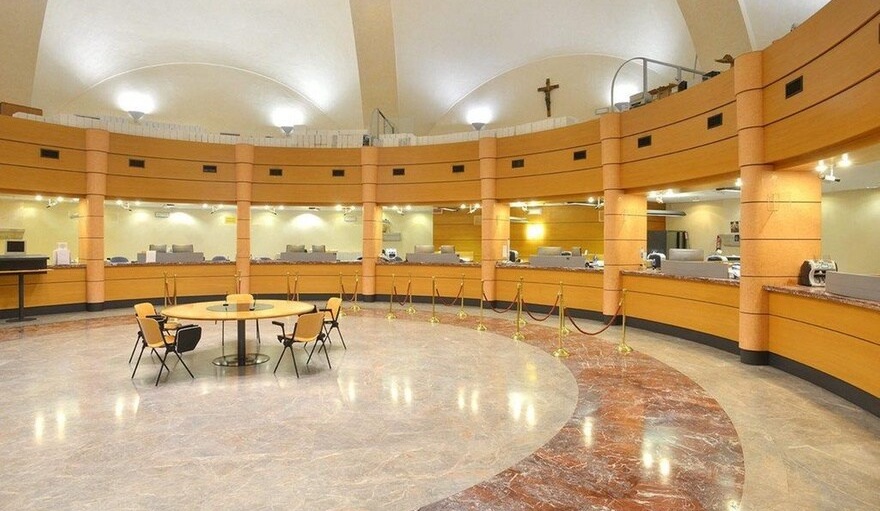

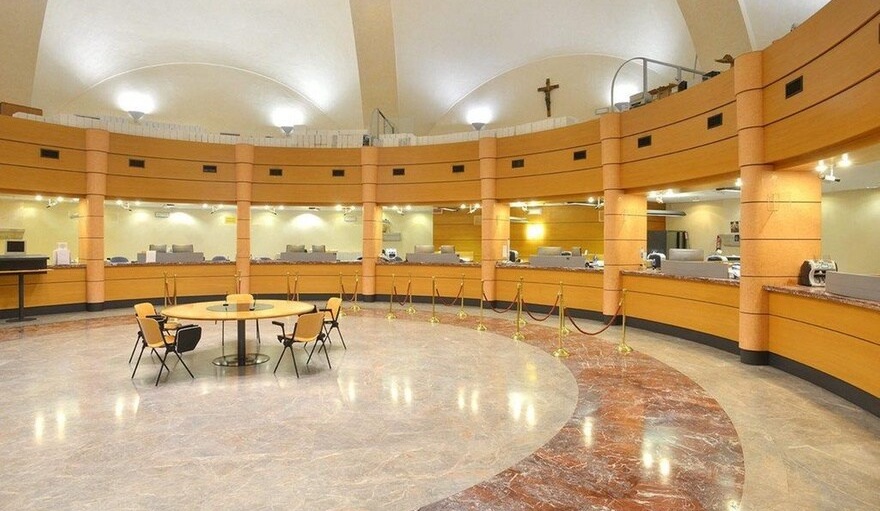

Vatican Bank from the inside.

The Vatican Bank was founded in June 1942 by Pope Pius XII. The bank's official website states that the IOR is neither part of the Papal Curia nor the central administrative structure of the Roman Catholic Church. The financial institution is governed by an advisory board that reports directly to the Pope and a committee of cardinals. It is also noted that the main function of the bank is "to ensure the safety and management of movable and immovable property entrusted to it by various people and intended for religious or charitable purposes."

The Vatican Bank is different from many other banks. He does not issue loans or make direct investments. The bank receives money as deposits, and then invests it in government and corporate bonds, as well as in other participants in the interbank market.

After an unsuccessful 2018 in 2019, the bank reported a twofold increase in profit from 17.5 million to 38 million euros. According to the IOR's financial report, at the end of the year, the bank's net capital was 630.3 million euros, and the volume of client assets increased to 5.1 billion euros.

In The Godfather 3, mobster Michael Corleone meets with the head of the Vatican Bank.

The Vatican Bank openly admits that it faced repeated criticism regarding investments, personnel appointments and the use of funds, which led to several scandals with the subsequent dismissal of its top managers.

In addition to allegations of illegal financial transactions and dubious investments, the bank has also been associated with the Italian mafia. At the center of one of the most high-profile scandals was the American Paul Marcinkus, who headed the bank from 1971 to 1989.

In 1982, Marcinkus was compromised by the bankruptcy of the Italian Banco Ambrosiano, which left behind $ 1.5 billion in debt. Then IOR owned about 1.5% of the shares of the Italian bank - at that time the largest private investment company in the country with close ties to the Holy See. According to The Irish Times, part of Banco Ambrosiano's money was lent to 10 offshore companies controlled by the IOR and directly by Marcinkus.

The head of Banco Ambrosiano, Roberto Calvi, was on friendly terms with Marcinkus. The latter, due to his financial position, was at the top of the Roman elite. According to Esquire magazine, Marcinkus accepted contributions from mafia families, and the most generous bandits received special letters of recommendation from the bishop.

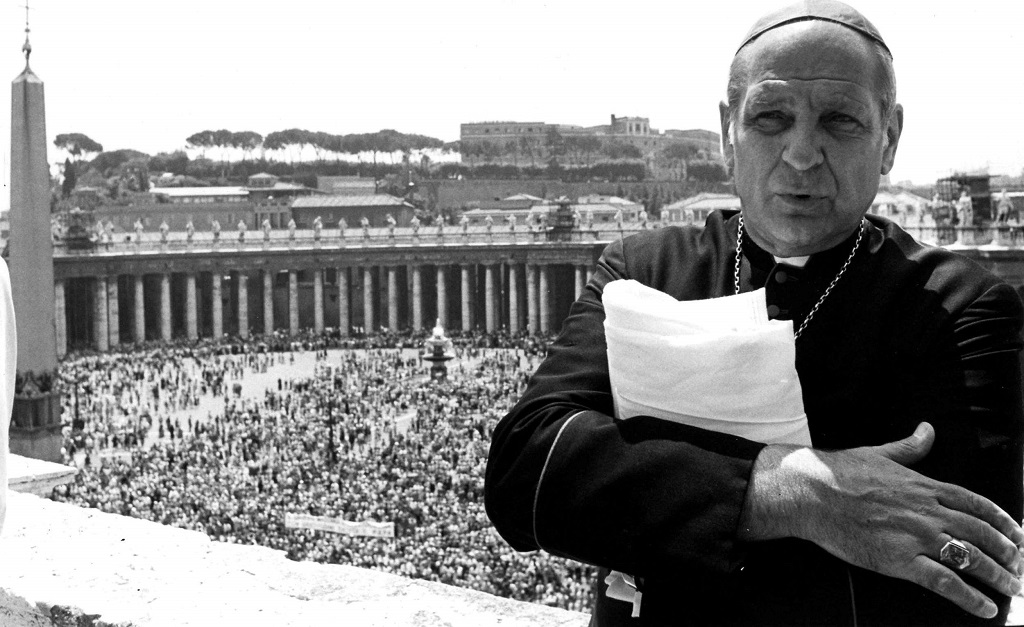

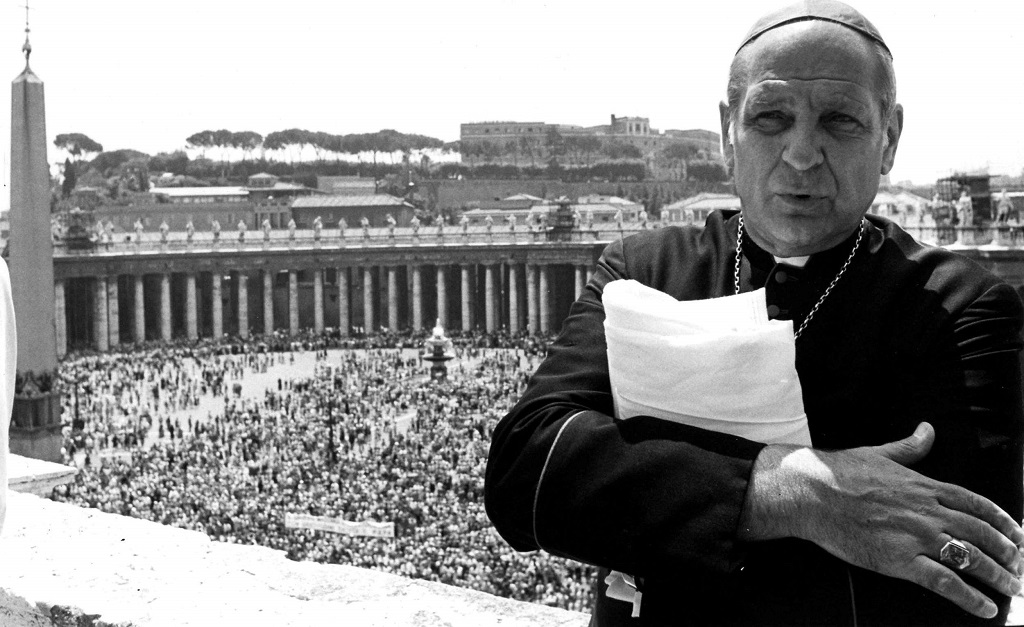

Paul Marcinkus headed the Vatican Bank for almost 20 years.

Calvi, who was found guilty of financial fraud, disappeared on appeal. In June 1982, he was found hanged under a bridge in London. Initially, his death was considered a suicide, but after reports of his alleged links with the mafia, the case was reclassified as a murder. In October 2005, five people were brought to trial in Rome on charges of his death.

While investigating the Banco Ambrosiano's machinations, Marcinkus chose to hide from the public at the Vatican, refusing to answer questions about the church's role in creating shell companies. Later, letters were found that clearly indicated that he guaranteed the protection of the capital investments of creditors. He publicly commented on the situation only after his retirement: “Italians should have figured out their own banking system. It is very easy to pin the blame on someone else. I've never done anything wrong. "

Another high-profile scandal occurred in May 2012, when Ettore Gotti Tedeschi was fired from the post of head of the Vatican bank. The financier was accused of abuse of office and laundering 23 million euros. After years of litigation, Tedeschi was cleared of fraud charges.

Just a year after Tedeschi's arrest at the end of June 2013, Italian police arrested the priest Nunzio Scarano. The churchman was nicknamed "Monsignor Cinquecento" (from Italian. Cinquecento - five hundred) because of his preference to pay with brand new 500 euro bills. Together with a former Secret Service agent and financial broker, he was accused of fraud and corruption. All three were suspected of trying to fly 20 million euros in a private jet from Switzerland to Italy.

Prosecutors alleged that Scarano, who previously served as head of the accounting department at the Vatican treasury, used the IOR to transfer money to businessmen from Naples, a region considered to be an organized crime haven in Italy. Three years later, a court in Rome acquitted Scarano in the money smuggling case, but found him guilty of defamation of other defendants in the case and gave him a two-year suspended sentence.

View of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican.

In the same 2013, the Financial Times published the results of an 11-month investigation, which revealed the extent of official abuse of bank assets worth 5 billion euros. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, regulators tightened their scrutiny of financial institutions, bringing Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan and UniCredit to their attention due to their ties to the Vatican.

In total, according to the Financial Times, about three dozen banks, including some of the largest financial institutions in the world, have been correspondent banks of the Vatican for many years. As with other institutional clients, banks have provided the church state with access to foreign financial markets. The FT, referring to a Vatican spokesman, said that such correspondent banks transferred up to 2 billion euros per year from the IOR to other accounts around the world.

Numerous financial scandals eventually prompted the newly elected Pope Francis in 2013 to implement reforms aimed at improving financial accountability and transparency of the institution.

The soon-to-be-appointed president of the IOR, German lawyer Ernst von Freiberg, spent 17 months carrying out large-scale reforms within the bank. He scrutinized the institute's client base, which resulted in the closure of 3.4 thousand accounts. The current head of the financial institution is the French financier Jean-Baptiste de France.

Nevertheless, the change in management did not save the bank from new scandals. In January 2021, a Vatican court sentenced 81-year-old Angelo Kaloia to eight years and 11 months in prison for money laundering and embezzlement. Kaloia, who served as president of the IOR from 1999 to 2009, was caught with two lawyers in the sale of the bank's Italian real estate. High-ranking businessmen have been running the scam for several years - from 2001 to 2008. Indeed, as Paul Marcinkus stated, “You can't run the Church on Hail Marys,” prayer alone is impossible.

How the Vatican Bank works.

The Vatican Bank, also known as the Institute for Religious Affairs (IOR), is a private financial institution located in the Vatican City State. The bank has been at the center of numerous scandals over the decades. Its leadership has faced allegations of mismanagement, money laundering, fraud, and mafia ties for years. Further in the article, the PaySpace Magazine editorial staff tells how the most closed bank in the world works.

Bank without loans and direct investments

Vatican Bank from the inside.

The Vatican Bank was founded in June 1942 by Pope Pius XII. The bank's official website states that the IOR is neither part of the Papal Curia nor the central administrative structure of the Roman Catholic Church. The financial institution is governed by an advisory board that reports directly to the Pope and a committee of cardinals. It is also noted that the main function of the bank is "to ensure the safety and management of movable and immovable property entrusted to it by various people and intended for religious or charitable purposes."

The Vatican Bank is different from many other banks. He does not issue loans or make direct investments. The bank receives money as deposits, and then invests it in government and corporate bonds, as well as in other participants in the interbank market.

According to official data for 2018, the bank allocated 55 million euros to the Vatican budget. On the website, this information is accompanied by the commentary that the IOR is “the most important economic pivot of the Italian city-state”.“The Vatican Bank is not responsible either for the monetary policy of the Vatican, or for the control of the money supply and the maintenance of currency stability. Nevertheless, the bank is a thriving and profitable institution, and all of its income is used for religious and charitable purposes, ”- from the description of the site.

After an unsuccessful 2018 in 2019, the bank reported a twofold increase in profit from 17.5 million to 38 million euros. According to the IOR's financial report, at the end of the year, the bank's net capital was 630.3 million euros, and the volume of client assets increased to 5.1 billion euros.

The most high-profile scandals of the Vatican bank: money laundering and connections with the Italian mafia

In The Godfather 3, mobster Michael Corleone meets with the head of the Vatican Bank.

The Vatican Bank openly admits that it faced repeated criticism regarding investments, personnel appointments and the use of funds, which led to several scandals with the subsequent dismissal of its top managers.

In addition to allegations of illegal financial transactions and dubious investments, the bank has also been associated with the Italian mafia. At the center of one of the most high-profile scandals was the American Paul Marcinkus, who headed the bank from 1971 to 1989.

In 1982, Marcinkus was compromised by the bankruptcy of the Italian Banco Ambrosiano, which left behind $ 1.5 billion in debt. Then IOR owned about 1.5% of the shares of the Italian bank - at that time the largest private investment company in the country with close ties to the Holy See. According to The Irish Times, part of Banco Ambrosiano's money was lent to 10 offshore companies controlled by the IOR and directly by Marcinkus.

The head of Banco Ambrosiano, Roberto Calvi, was on friendly terms with Marcinkus. The latter, due to his financial position, was at the top of the Roman elite. According to Esquire magazine, Marcinkus accepted contributions from mafia families, and the most generous bandits received special letters of recommendation from the bishop.

Paul Marcinkus headed the Vatican Bank for almost 20 years.

Calvi, who was found guilty of financial fraud, disappeared on appeal. In June 1982, he was found hanged under a bridge in London. Initially, his death was considered a suicide, but after reports of his alleged links with the mafia, the case was reclassified as a murder. In October 2005, five people were brought to trial in Rome on charges of his death.

While investigating the Banco Ambrosiano's machinations, Marcinkus chose to hide from the public at the Vatican, refusing to answer questions about the church's role in creating shell companies. Later, letters were found that clearly indicated that he guaranteed the protection of the capital investments of creditors. He publicly commented on the situation only after his retirement: “Italians should have figured out their own banking system. It is very easy to pin the blame on someone else. I've never done anything wrong. "

Another high-profile scandal occurred in May 2012, when Ettore Gotti Tedeschi was fired from the post of head of the Vatican bank. The financier was accused of abuse of office and laundering 23 million euros. After years of litigation, Tedeschi was cleared of fraud charges.

Just a year after Tedeschi's arrest at the end of June 2013, Italian police arrested the priest Nunzio Scarano. The churchman was nicknamed "Monsignor Cinquecento" (from Italian. Cinquecento - five hundred) because of his preference to pay with brand new 500 euro bills. Together with a former Secret Service agent and financial broker, he was accused of fraud and corruption. All three were suspected of trying to fly 20 million euros in a private jet from Switzerland to Italy.

Prosecutors alleged that Scarano, who previously served as head of the accounting department at the Vatican treasury, used the IOR to transfer money to businessmen from Naples, a region considered to be an organized crime haven in Italy. Three years later, a court in Rome acquitted Scarano in the money smuggling case, but found him guilty of defamation of other defendants in the case and gave him a two-year suspended sentence.

View of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican.

In the same 2013, the Financial Times published the results of an 11-month investigation, which revealed the extent of official abuse of bank assets worth 5 billion euros. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, regulators tightened their scrutiny of financial institutions, bringing Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan and UniCredit to their attention due to their ties to the Vatican.

In total, according to the Financial Times, about three dozen banks, including some of the largest financial institutions in the world, have been correspondent banks of the Vatican for many years. As with other institutional clients, banks have provided the church state with access to foreign financial markets. The FT, referring to a Vatican spokesman, said that such correspondent banks transferred up to 2 billion euros per year from the IOR to other accounts around the world.

Numerous financial scandals eventually prompted the newly elected Pope Francis in 2013 to implement reforms aimed at improving financial accountability and transparency of the institution.

The soon-to-be-appointed president of the IOR, German lawyer Ernst von Freiberg, spent 17 months carrying out large-scale reforms within the bank. He scrutinized the institute's client base, which resulted in the closure of 3.4 thousand accounts. The current head of the financial institution is the French financier Jean-Baptiste de France.

Nevertheless, the change in management did not save the bank from new scandals. In January 2021, a Vatican court sentenced 81-year-old Angelo Kaloia to eight years and 11 months in prison for money laundering and embezzlement. Kaloia, who served as president of the IOR from 1999 to 2009, was caught with two lawyers in the sale of the bank's Italian real estate. High-ranking businessmen have been running the scam for several years - from 2001 to 2008. Indeed, as Paul Marcinkus stated, “You can't run the Church on Hail Marys,” prayer alone is impossible.